Biology:Nectandra

| Nectandra | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nectandra saligna | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Laurales |

| Family: | Lauraceae |

| Genus: | Nectandra Rol. ex Rottb. |

| Species | |

|

See text. | |

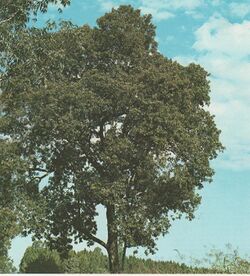

Nectandra is a genus of plant in the family Lauraceae. They are primarily Neotropical, with Nectandra coriacea being the only species reaching the southernmost United States.[1][2] They have fruit with various medical effects.[3] Sweetwood is a common name for some plants in this genus.[2]

Description

They are trees and bushes, hermaphrodites. The leaves are alternate, entire, glabrous or pubescent, pinnatinervias, with longitudinal grooves. Simple, alternate, petiole 0.9 to 2.2 cm in length canalicular limbo 11 to 28 cm long and 5 to 11 cm wide, with 16–28 secondary veins; base acute decurrent and revolute, entire, apex elliptically shaped, green dark, and very oblique secondary veins visible on the underside. terminal buds whitish. The inflorescences are pseudo-axillary, paniculate, the last divisions cimosas, mostly somewhat pubescent, the flowers are small, rarely more than 1 cm in diameter, white or greenish tepals equal. The fruit is an ovoid fleshy drupe with a reddish-pink dome, green when immature and black when ripe.

Ecology

A neotropical genus with 114 species, the genus is similar to Ocotea, to which it is closely related: the most characteristic distinguishing features are the position of the locules in the anther (in an arc in Nectandra and in 2 rows in Ocotea); papillose pubescence is present; the Nectandra petals are fused at the base itself and fall as a unit in the old flowers; they are free in Nectandra but in Ocotea fall individually.

Medium trees reach 60 cm in diameter and 25 m in height with straight, slender, cylindrical boles that have low and thin protuberances at the base. The various species are located in the middle stratum of forests. Many species are used as timber.[4]

The family Lauraceae was part of the Gondwanaland flora and many of its genera migrated to South America via Antarctica on ocean landbridges in the Paleocene era. There they spread over most of the continent. When the North American and South American tectonic plates joined in the late Neogene, volcanic mountain building created island chains which later formed the meso-American landbridge. Pliocene elevation created new habitats for speciation. While some genera died out in increasingly xerophytic Africa, starting with the freezing of Antarctica about 20 million years ago and the formation of the Benguela current, others, like Beilschmiedia, and Nectandra, which also reached south and meso-America, are still surviving today in Africa in a number of species. The genus Persea, however, died out in Africa, except for Persea indica, surviving in the fog shrouded mountains of the Canary Islands, which with Madagascar constitutes Africa's Laurel forest plant refugia. In meso-America, the genus Nectandra proliferated into new species and the berries of some of them constitute a valuable food supply for the quetzal bird that lives in the montane rainforests of meso-America. Since this habitat is constantly threatened by encroaching agriculture, the laurel forest animal and plant species had already become rare in many of its former habitats and are threatened by habitat loss.

The quetzal's favorite fruits are berries of relatives of Nectandra umbrosa. Their differing maturing times in the Cloud forest determine the migratory movements of the quetzals to differing elevation levels in the forests. With a gape width of 21 mm, the quetzal swallows the small berries (aquacatillos) whole, which he catches while flying through the lower canopy of the tree, and then regurgitates the seed within 100 meters from the tree. Wheelright in 1983 observed that parent quetzals take far less time intervals to deliver fruits to the young brood than insects or lizards, reflecting the ease of procuring fruits, as opposed to capturing animal prey. Since the young are fed exclusively berries in the first 2 weeks after hatching, these berries must be of high nutritional value. Usually only the total percentage of water, sugar, nitrogen, crude fats and carbohydrates are reported by ornithologists[5]

Medical use

Plants from this genus have been used in the treatment of several clinical disorders in humans. It has been demonstrated that Nectandra plants have potential analgesic, anti-inflammatory, febrifuge, energetic and hypotensive activities. Nectandra also has been investigated as a possible antitumoral agent and the presence of neolignans suggests its potential use as a source of chemotherapeutics. Crude extracts of Nectandra contain alkaloids and lignans, berberine and sipirine. Some authors have postulated that tannins play important roles as antioxidant compounds in the scavenging of free radicals. It is reported that an extract of N. salicifolia has potent relaxant activity on vascular smooth muscle. Researchers of the entire world agree that pre-clinical large studies on herbal medicine are important and urgent, specially high-quality clinical and pre-clinical trials.[3]

In pre-Columbian Peru the seeds, called amala in Spanish, were used as a muscle relaxant. In sites of the Sican culture, collections of the seeds have been associated with human sacrifice, and used to incapacitate victims prior to being killed.[6][7][8]

Selected species

Nectandra contains approximately 120 species,[1] including the following:

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Henk van der Werff. "Nectandra Rottbøll". Flora of North America. www.efloras.org. http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=121755.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Nectandra". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=NECTA2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ramos Farías Moreno, Silvana; Arnobio, Adriano; Carvalho, Jorge José De; Nascimento, Lucia; Oliveira Timoteo, Margareth; Olej, Beni; Kazan Rocha, Emely; Pereira, Mario et al. (2007). "The ingestion of a Nectandra membranacea extract changes the bioavailability of technetium-99m radiobiocomplex in rat organs". Biological Research 40 (2): 131–135. doi:10.4067/S0716-97602007000200004. PMID 18064350. http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0716-97602007000200004.

- ↑ "Manual dendrológico de las principales especies de interés comercial actual y potencial de la zona del Alto Huallaga" (in es). http://www.cnf.org.pe/enero011/MD.pdf.

- ↑ Phytochemistry of Nectandra umbrosa Berries, Cloudforest Food of the Resplendent Quetzal avocadosource.com

- ↑ The Cursed Valley of the Pyramids, Season 1, Episode 2 of Lost Cities of the Ancients. Directed by Aidan Laverty. BBC.IMDB

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://www.encuentrocientificointernacional.org/revista/eci2007vvol4num1.pdf.

- ↑ "Amala seed -The Entheogen Network". http://www.entheogen-network.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=10&t=22647.

- ↑ de Kok, R. (2021). "Nectandra turbacensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T143822730A143953306. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T143822730A143953306.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/143822730/143953306. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

Wikidata ☰ Q3312303 entry

|