Biology:Rhus michauxii

| Rhus michauxii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Anacardiaceae |

| Genus: | Rhus |

| Species: | R. michauxii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Rhus michauxii Sarg.

| |

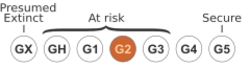

Rhus michauxii is a rare species of flowering plant in the cashew family known by the common names false poison sumac[4] and Michaux's sumac. It is endemic to the southeastern United States, where it can be found in the states of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.[1] It is threatened by the loss and degradation of its habitat and by barriers to reproduction. It is a federally listed endangered species of the United States.[2]

This plant is a small shrub growing 30 to 60 centimetres (12 to 24 in) tall. It is very hairy in texture. The small size and hairiness distinguish the plant from other sumacs. The long leaves are each made up of several pairs of toothed leaflets. The plant is dioecious with male and female reproductive parts occurring on separate plants. The plant produces an erect inflorescence of white or greenish yellow flowers in June that develop into red drupes in female plants in late summer to early fall.[3]:39853-39854 This plant was first described as Rhus pumila by André Michaux in 1803, and it was renamed for Michaux in 1895.[5]

This shrub grows in wooded areas often on clay or decomposed granite soils. It occurs in sandhills habitat in loamy soils. The habitat may be dominated by longleaf pine and oaks and it may grow alongside Ceanothus americanus, Paspalum bifidum, Tridens carolinianus, Aristida lanosa, Onosmodium virginianum, and Helianthus divaricatus. Other associates and indicators of the plant include Liquidambar styraciflua, Cornus florida, Rhus glabra, R. copallinum, Schizachyrium scoparium Sorghastrum elliottii, Brickellia eupatorioides, Eupatorium godfreyanum, E. sessilifolium, Silphium compositum, Helianthus divaricatus, Helianthus strumosus, Viburnum rafinesquianum, Scleria oligantha, Clematis ochroleuca, Sanicula smallii, Salvia urticifolia, and Parthenium auriculatum. The area is generally somewhat more moist than surrounding habitat types.[1] The plant requires openings in the vegetation so it can receive sunlight.[6]

Half of the recorded populations of this plant have been extirpated.[6] Much of its habitat has been cleared for residential, industrial, and agricultural operations, including silviculture, and the construction of roads. Remaining habitat is degraded by the lack of a normal fire regime. The plant does not tolerate shade and it grows naturally in openings maintained by wildfire. Today, fire suppression is practiced and normal periodic wildfires are prevented. The result is overgrowth of the vegetation, which shades out the rare shrub.[1]

This plant also has difficulty reproducing. It is clonal, often reproducing vegetatively, so populations are low in genetic variability.[1] It may hybridize with the common Rhus glabra.[7] This union forms Rhus × ashei, a natural hybrid. One major reproductive problem is that many populations are composed entirely of one sex. Furthermore, the populations are small and very widely spaced, making reproduction impossible. As the plant requires open habitat, it may arise in artificially cleared areas such as roadsides. There it is vulnerable to destruction from construction, maintenance, and herbicides.[1]

Conservation activities include genetic analysis in an effort to understand the genetic variability of populations. Plant propagation techniques are being studied. Plants are being reintroduced to appropriate habitat, including the placement of opposite-sex plants into single-sex populations.[6] Plants are transplanted from high-risk areas to better habitat for their survival.[8] Prescribed burns help to create openings where the plant can thrive.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 NatureServe (3 November 2023). "Rhus michauxii". Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.148771/Rhus_michauxii.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Michaux's sumac (Rhus michauxii)". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/species/5217.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Murdock, Nora; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (28 September 1989). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Determination of Endangered Status for Rhus Michauxii (Michaux's Sumac)". Federal Register 54 (187): 39853-39857. 54 FR 39853

- ↑ "Rhus michauxii". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=RHMI11. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ Barden, L.S.; Matthews, J.F. (2004). "André Michaux's Sumac: Rhus michauxii Sargent: Why did Sargent rename it and where did Michaux find it?". Castanea 69 (2): 109-115.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Rhus michauxii. Center for Plant Conservation.

- ↑ Burke, J.M.; Hamrick, J.L. (2002). "Genetic Variation and Evidence of Hybridization in the Genus Rhus (Anacardiaceae)". Journal of Heredity 93 (1): 37-41. doi:10.1093/jhered/93.1.37. PMID 12011173.

- ↑ Braham, R.; Murray, C.; Boyer, M. (2006). "Mitigating impacts to Michaux's Sumac (Rhus michauxii Sarg.): A case study of transplanting an endangered shrub". Castanea 71 (4): 265-271.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q7321566 entry

|