Biology:Pinus edulis

| Pinus edulis | |

|---|---|

| |

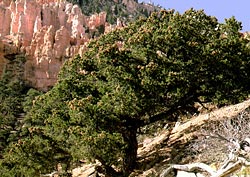

| Colorado pinyons at Bryce Canyon National Park | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnospermae |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Genus: | Pinus |

| Subgenus: | P. subg. Strobus |

| Section: | P. sect. Parrya |

| Subsection: | P. subsect. Cembroides |

| Species: | P. edulis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pinus edulis | |

| |

| Natural range of Pinus edulis | |

Pinus edulis, the Colorado pinyon, two-needle piñon, pinyon pine, or simply piñon,[2] is a pine in the pinyon pine group whose ancestor was a member of the Madro-Tertiary Geoflora[3][lower-alpha 1] (a group of drought resistant trees) and is native to the United States .

Distribution and habitat

The range in the U.S. is in Colorado, southern Wyoming, eastern and central Utah, northern Arizona, New Mexico, western Oklahoma, southeastern California, and the Guadalupe Mountains in far western Texas , as well as northern Mexico.[5] It occurs at moderate elevations of 1,600–2,400 metres (5,200–7,900 ft), rarely as low as 1,400 m (4,600 ft) and as high as 3,000 m (9,800 ft). It is widespread and often abundant in this region, forming extensive open woodlands, usually mixed with junipers in the pinyon-juniper woodland plant community. The Colorado pinyon (piñon) grows as the dominant species on 4.8 million acres (19,000 km2 or 7,300 sq mi) in Colorado, making up 22% of the state's forests. The Colorado pinyon has cultural meaning to agriculture, as strong piñon wood "plow heads" were used to break soil for crop planting at the state's earliest known agricultural settlements.

There is one known example of a Colorado pinyon growing amongst Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii) and limber pine (Pinus flexilis) at nearly 3,170 metres (10,400 ft) on Kendrick Peak in the Kaibab National Forest of northern Arizona.

Description

The piñon pine (Pinus edulis) is a small to medium size tree, reaching 10–20 feet (3.0–6.1 m) tall and with a trunk diameter of up to 80 centimetres (31 in), rarely more. Its growth is "at an almost inconceivably slow rate" growing only six feet (1.8 meters) in one hundred years under good conditions.[6] for an average growth of 0.72 inch (18 millimeters)per year. The bark is irregularly furrowed and scaly. The leaves ('needles') are in pairs, moderately stout, 3–5.5 cm (1 1⁄8–2 1⁄8 in) long, and green, with stomata on both inner and outer surfaces but distinctly more on the inner surface forming a whitish band.

The cones are globose, 3–5 cm (1 1⁄4–2 in) long and broad when closed, green at first, ripening yellow-buff when 18–20 months old, with only a small number of thick scales, with typically 5–10 fertile scales. The cones open to 4–6 cm (1 1⁄2–2 1⁄4 in) broad when mature, holding the seeds on the scales after opening. The seeds are 10–14 mm (3⁄8–9⁄16 in) long, with a thin shell, a white endosperm, and a vestigial 1–2 mm (1⁄32–3⁄32 in) wing.

The species intermixes with Pinus monophylla sbsp. fallax (see description under Pinus monophylla) for several hundred kilometers along the Mogollon Rim of central Arizona and the Grand Canyon resulting in trees with both single- and two-needled fascicles on each branch. The frequency of two-needled fascicles increases following wet years and decreases following dry years.[7] The internal anatomy of both these needle types are identical except for the number of needles in each fascicle suggesting that Little's 1968 designation [8] of this tree as a variety of Pinus edulis is more likely than its subsequent designation as a subspecies of Pinus monophylla based entirely upon its single needle fascicle.

It is an aromatic species. Essential oil can be extracted from the trunk, limbs, needles, and seed cones. Prominent aromatic compounds from each portion of the tree include α-pinene, sabinene, β-pinene, δ-3-carene, β-phellandrene, ethyl octanoate, longifolene, and germacrene D.[9]

Ecology

The seeds are dispersed by the pinyon jay, which plucks them out of the open cones. The jay, which uses the seeds as a food resource,[10] stores many of the seeds for later use, and some of these stored seeds are not used and are able to grow into new trees. The seeds are also eaten by wild turkey, Montezuma quail, and various mammals.[11]

History

Colorado pinyon was described by George Engelmann in 1848 from collections made near Santa Fe, New Mexico on Alexander William Doniphan's expedition to northern Mexico in 1846.

It is most closely related to the single-leaf pinyon, which hybridises with it occasionally where their ranges meet in western Arizona and Utah. It is also closely related to the Texas pinyon, but is separated from it by a gap of about 100 kilometres (62 mi) so does not hybridise with it.

An isolated population of trees in the New York Mountains of southeast California , previously thought to be Colorado pinyons, have recently been shown to be a two-needled variant of single-leaf pinyon from chemical and genetic evidence. Occasional two-needled pinyons in northern Baja California, Mexico have sometimes been referred to Colorado pinyon in the past, but are now known to be hybrids between single-leaf pinyon and Parry pinyon.

Uses

The edible seeds,[10] pine nuts, are extensively collected throughout its range; in many areas, the seed harvest rights are owned by Native American tribes, for whom the species is of immense cultural and economic importance.[citation needed][12] They can be stored for a year when unshelled.[11]

Archaeologist Harold S. Gladwin described pit-houses constructed by southwestern Native Americans c. 400–900 CE; these were fortified with posts made from Pinyon trunks and coated with mud.[13]

Colorado pinyon is also occasionally planted as an ornamental tree and sometimes used as a Christmas tree.

The piñon pine (Pinus edulis) is the state tree of New Mexico.

See also

References

- ↑ This designation has as a part of it a term, 'Tertiary', that is now discouraged as a formal geochronological unit by the International Commission on Stratigraphy.[4]

- ↑ Farjon, A. (2013). "Pinus edulis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T42360A2975133. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42360A2975133.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/42360/2975133. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ "New Mexico Secretary of State: KID'S Corner". http://www.sos.state.nm.us/KidsCorner/StateSymbols.html.

- ↑ Axelrod, Daniel I. (July 1958). "Evolution of the madro-tertiary geoflora". The Botanical Review 24 (7): 433–509. doi:10.1007/BF02872570. http://www.wou.edu/~mcgladm/Geography%20313%20Pacific%20Northwest/for%20exam%201%20physical%20landscape/optional/Madro%20Tertiary%20Geoflora%20Axelrod.pdf.

- ↑ Ogg, James G.; Gradstein, F. M.; Gradstein, Felix M. (2004). A geologic time scale 2004. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78142-6.

- ↑ Moore, Gerry; Kershner, Bruce; Craig Tufts; Daniel Mathews; Gil Nelson; Spellenberg, Richard; Thieret, John W.; Terry Purinton et al. (2008). National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Trees of North America. New York: Sterling. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-4027-3875-3.

- ↑ Rehorn, John T. (Winter–Spring 1997). "The Gift". American Forests 103 (1): 28 caption.

- ↑ Cole, Ken; Fisher, Jessica; Arundel, Samantha; Canella, John; Swift, Sandra (2008). "Geographical and climatic limits of needle types of one- and two-needled pinyon pines". Journal of Biogeography 35 (2): 357–369. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01786.x. PMID 21188300.

- ↑ Little, Elbert (1968). "Two new pinyon varieties from Arizona". Phytologia 17: 329–342.

- ↑ Poulson A, Wilson TM, Packer C, Carlson RE, Buch RM. "Essential oils of trunk, limbs, needles, and seed cones of Pinus edulis (Pinaceae) from Utah". Phytologia 102 (3): 200–207.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Whitney, Stephen (1985). Western Forests (The Audubon Society Nature Guides). New York: Knopf. p. 414. ISBN 0-394-73127-1. https://archive.org/details/westernforests00whit/page/414.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Peattie, Donald Culross (1953). A Natural History of Western Trees. New York: Bonanza Books. pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Fischer, Karen (December 6, 2021). "In New Mexico, Money Grows on Trees". https://www.eater.com/22812750/picking-selling-business-pinon-nuts-harvest-new-mexico-navajo-nation.

- ↑ Peattie, Donald Culross (1953). A Natural History of Western Trees. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 70.

- Ronald M. Lanner, 1981. The Piñon Pine: A Natural and Cultural History. University of Nevada Press. ISBN:0-87417-066-4.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q133096 entry

|