Biology:Platanus occidentalis

| American sycamore | |

|---|---|

| |

| An eight-foot diameter sycamore in Sunderland, MA | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Platanaceae |

| Genus: | Platanus |

| Species: | P. occidentalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Platanus occidentalis | |

| |

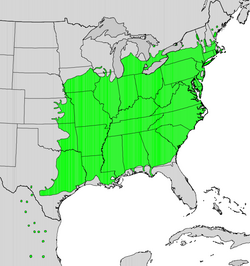

| Generalized natural range of Platanus occidentalis | |

Platanus occidentalis, also known as American sycamore, American planetree, western plane,[2] occidental plane, buttonwood, and water beech,[3] is a species of Platanus native to the eastern and central United States, the mountains of northeastern Mexico, extreme southern Ontario,[4][5] and extreme southern Quebec.[6] It is usually called sycamore in North America, a name which can refer to other types of trees in other parts of the world. The American sycamore is a long-lived species, typically surviving at least 200 years and likely as long as 500–600 years.[7]

The species epithet occidentalis is Latin for "western", referring to the Western Hemisphere, because at the time when it was named by Carl Linnaeus, the only other species in the genus was P. orientalis ("eastern"), native to the Eastern Hemisphere. Confusingly, in the United States, this species was first known in the Eastern United States, thus it is sometimes called eastern sycamore,[8][9] to distinguish it from Platanus racemosa which was discovered later in the Western United States and called western sycamore.

Description

Platanus occidentalis can often be easily distinguished from other trees by its mottled bark which flakes off in large irregular masses, leaving the surface mottled and gray, greenish-white and brown. The bark of all trees has to yield to a growing trunk by stretching, splitting, or infilling, but sycamore bark is more rigid and less elastic than the bark of other trees, so to accommodate the growth of the wood underneath, the tree sheds it in large, brittle pieces.[10]

A sycamore can grow to massive proportions, typically reaching up to 30 to 40 m (98 to 131 ft) high and 1.5 to 2 m (4.9 to 6.6 ft) in diameter when grown in deep soils. The largest of the species have been measured to 53 m (174 ft), and nearly 4 m (13 ft) in diameter. Larger specimens were recorded in historical times. In 1744, a Shenandoah Valley settler named Joseph Hampton and two sons lived for most of the year in a hollow sycamore in what is now Clarke County, Virginia.[11] In 1770, at Point Pleasant, Virginia (now in West Virginia),[12] near the junction of the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers, George Washington recorded in his journal a sycamore measuring 13.67 m (44 ft 10 in) in circumference at 91 cm (3 ft) from the ground.[13]

The sycamore tree is often divided near the ground into several secondary trunks, very free from branches. Spreading limbs at the top make an irregular, open head. Roots are fibrous. The trunks of large trees are often hollow.

Another peculiarity is the way the leaves grow sticky, green buds. In early August, most trees will have tiny buds nestled in the axils of their leaves which will produce the leaves of the coming year. The sycamore branch apparently has no such buds. Instead there is an enlargement of the petiole which encloses the bud in a tight-fitting case at the base of the petiole.[10]

- Bark: Dark reddish brown, broken into oblong plate-like scales; higher on the tree, it is smooth and light gray; separates freely into thin plates which peel off and leave the surface pale yellow, or white, or greenish. Branchlets at first pale green, coated with thick pale tomentum, later dark green and smooth, finally become light gray or light reddish brown.

- Wood: Light brown, tinged with red; heavy, weak, difficult to split. Largely used for furniture and interior finish of houses, butcher's blocks. Specific gravity, 0.5678; relative density, 0.53724 g/cm3 (33.539 lb/cu ft).

- Winter buds: Large, stinky, sticky, green, and three-scaled, they form in summer within the petiole of the full-grown leaf. The inner scales enlarge with the growing shake. There is no terminal bud.

- Leaves: Alternate, palmately nerved, broadly ovate or orbicular, 10 to 23 cm (4 to 9 in) long, truncate or cordate or wedge-shaped at base, decurrent on the petiole. Three to five-lobed by broad shallow sinuses rounded in the bottom; lobes acuminate, toothed, or entire, or undulate. They come out of the bud plicate, pale green coated with pale tomentum; when full grown are bright yellow green above, paler beneath. In autumn they turn brown and wither before falling. Petioles long, abruptly enlarged at base and inclosing the buds. Stipules with spreading, toothed borders, conspicuous on young shoots, caducous.

- Flowers: May, with the leaves; monoecious, borne in dense heads. Staminate and pistillate heads on separate peduncles. Staminate heads dark red, on axillary peduncles; pistillate heads light green tinged with red, on longer terminal peduncles. Calyx of staminate flowers three to six tiny scale-like sepals, slightly united at the base, half as long as the pointed petals. Of pistillate flowers three to six, usually four, rounded sepals, much shorter than the acute petals. Corolla of three to six thin scale-like petals.

- Stamens: In staminate flowers as many of the divisions of the calyx and opposite to them; filaments short; anthers elongated, two-celled; cells opening by lateral slits; connectives hairy.

- Pistil: Ovary superior, one-celled, sessile, ovate-oblong, surrounded at base by long, jointed, pale hairs; styles long, incurved, red, stigmatic, ovules one or two.

- Fruit: Brown heads, solitary or rarely clustered, 2.5 cm (1 in) in diameter, hanging on slender stems three to six inches long; persistent through the winter. These heads are composed of achenes about two-thirds of an inch in length. October.[10]

Distribution

In its native range, it is often found in riparian and wetland areas. The range extends from Iowa to Ontario and New Hampshire in the north, Nebraska in the west, and south to Texas and Florida. It is apparently extirpated from Maine.[14] Closely related species (see Platanus) occur in Mexico and the southwestern states of the United States. It is sometimes grown for timber and has become naturalized in some areas outside its native range. It can be found growing successfully in Bismarck, North Dakota,[15] and it is sold as far south as Okeechobee. The American sycamore is also well adapted to life in Argentina and Australia and is quite widespread across the Australian continent, especially in the cooler southern states such as Victoria and New South Wales.

Ecology

American sycamore is found most commonly in bottomland or floodplain areas, thriving in the wet environments provided by rivers, streams, or abundant groundwater, though it will die after being flooded for more than two weeks at a time.[16] It is a fast-growing, early-mid successional hardwood tree species.[17] Its life cycle follows the pattern of a "weedy" species: it grows mature enough to reproduce rather young and produces large numbers of wind-distributed seeds.[18] The dominance of sycamore in a forest depends on the conditions where it grows; it is often a pioneer species, but in the wet sites that are most ideal for it, it persists as a subclimax to climax species, partly because of its fast growth and very long lifespan.[16]

As one of the largest trees in the wet bottomland habitats where it dominates, it is a key component of the structure of those habitats.[19] The heartwood of a sycamore tree decays quickly, producing large hollow cavities in the center of the trees which are used by many animals as nesting sites.[18] The largest hollow trees can be big enough for black bear dens, but average trees create homes for bats and cavity-nesting birds like wood ducks, barred owls, screech owls, chimney swift, and great-crested flycatcher.[19]

As host plant

American sycamore is the host plant of the sycamore tussock moth, a species which specializes in it, and a major host plant for the drab prominent moth.[19] This plant is also the first host known for Plagiognathus albatus.[20]

Uses

The American sycamore is able to endure a big city environment and was formerly extensively planted as a shade tree,[10] but due to the defacing effects of anthracnose it has been largely usurped in this function by the resistant London plane.[21]

Its wood has been used extensively for butcher's blocks. It has been used for boxes and crates; although coarse-grained and difficult to work, it has also been used to make furniture, siding, and musical instruments.[21]

Investigations have been made into its use as a biomass crop.[22]

Use by Native Americans

The tree bark has traditionally been used by Native Americans to make little dishes for gathering whortleberries.[23]

Pests and diseases

The American sycamore is a favored food plant of the pest sycamore leaf beetle.

American sycamore is susceptible to plane anthracnose disease (Apiognomonia veneta, syn. Gnomonia platani), an introduced fungus found naturally on the Oriental plane P. orientalis, which has evolved considerable resistance to the disease. Although rarely killed or even seriously harmed, American sycamore is commonly partially defoliated by the disease, rendering it unsightly as a specimen tree.

Sometimes mistaken for frost damage, the disease manifests in early spring, wilting new leaves and causing mature leaves to turn brown along the veins. Infected leaves typically shrivel and fall, so that by summer the tree is regrowing its foliage. Cankers form on twigs and branches near infected leaves, serving to spread the disease by spore production and also weakening the tree. Because cankers restrict the flow of nutrients, twigs and branches afflicted by cankers eventually die. Witch's broom is a symptom reflecting the cycle of twigs dying.[24]

As a result of the fungus' damage, American sycamore is often avoided as a landscape tree, and the more resistant London plane (P. × hispanica; hybrid P. occidentalis × P. orientalis) is planted instead.

History

The terms under which the New York Stock Exchange was formed are called the "Buttonwood Agreement", because it was signed under a buttonwood (sycamore) tree at 68 Wall Street, New York City in 1792.

The sycamore made up a large part of the forests of Greenland and Arctic America during the Cretaceous and Tertiary periods. It once grew abundantly in central Europe, from which it has now disappeared.[10] It was brought to Europe early in the 17th century.[25]

See also

- Buttonball Tree, an American sycamore, said to be the largest on the East Coast, located in Sunderland, Massachusetts

- Pinchot Sycamore, an American sycamore that is the largest tree in Connecticut

- Webster Sycamore, formerly the largest American sycamore in West Virginia

- Sycamore maple or European sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus), a maple which is visually very similar to sycamore

References

- ↑ Stritch, L. (2018). "Platanus occidentalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T61956705A136056183. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T61956705A136056183.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/61956705/136056183. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ "Platanus occidentalis". Trees and Shrubs Online. https://treesandshrubsonline.org/articles/platanus/platanus-occidentalis/.

- ↑ Alden, Harry A. (1994). "Fact Sheet for Platanus occidentalis". Center for Wood Anatomy Research. https://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/TechSheets/HardwoodNA/htmlDocs/platan1.html.

- ↑ "Platanus occidentalis", County-level distribution map from the North American Plant Atlas (NAPA) (Biota of North America Program (BONAP)), 2014, http://bonap.net/MapGallery/County/Platanus%20occidentalis.png

- ↑ Sullivan, Janet (1994), Platanus occidentalis, US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Forest Service (USFS), Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/plaocc/all.html

- ↑ Gingras, Pierre. "Un nouvel arbre au Québec". La Presse. https://www.lapresse.ca/maison/cour-et-jardin/jardiner/201010/14/01-4332445-un-nouvel-arbre-au-quebec.php.

- ↑ "USDA Plant Guide: American Sycamore". https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/plantguide/pdf/cs_ploc.pdf.

- ↑ "Eastern Sycamore". Cornell Botanic Gardens. https://cornellbotanicgardens.org/plant/eastern-sycamore/.

- ↑ "Platanus occidentalis - Plant Finder". Missouri Botanical Garden. https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=285137.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Keeler, Harriet L. (1900). Our Native Trees and How to Identify Them. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 263–268. https://archive.org/details/ournativetreesa02keelgoog.

- ↑ Kercheval, Samuel (1833). A History of the Valley of Virginia. Samuel H. Davis. pp. 74. https://archive.org/stream/ahistoryvalleyv01jacogoog#page/n58.

- ↑ "George Washington and the Great Kanawha Valley". http://www.galliagenealogy.org/History/washington.htm.

- ↑ Dale Luthringer (2007-03-22). "Historical sycamore dimensions". Eastern Native Tree Society. http://www.nativetreesociety.org/historic/historical_sycamore_dimensions.htm.

- ↑ "Maine Natural Areas Program Rare Plant Fact Sheet for Platanus occidentalis". http://www.maine.gov/dacf/mnap/features/plaocc.htm.

- ↑ "2018 Register of Champion Trees". NDSU–North Dakota Forest Service. https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/ndfs/documents/champ-tree-register-18-revised-04-15-2019.pdf.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Wells, O.O.; Schmidtling, R.C.. "Sycamore". United States Department of Agriculture. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_2/platanus/occidentalis.htm.

- ↑ Lázaro-Lobo, Adrián; Lucardi, Rima D.; Ramirez‐Reyes, Carlos; Ervin, Gary N. (March 2021). "Region-wide assessment of fine-scale associations between invasive plants and forest regeneration". Forest Ecology and Management 483: 118930. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2021.118930.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Paratley, Rob. "Economic Botany and Cultural History: Sycamore". University of Kentucky. https://ufi.ca.uky.edu/treetalk/ecobot-sycamore.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis)". https://bplant.org/plant/158.

- ↑ Wheeler, A. G. (15 July 1980). "Life History of Plagiognathus albatus (Hemiptera: Miridae), with a Description of the Fifth Instar". Annals of the Entomological Society of America 73 (4): 354–356. doi:10.1093/aesa/73.4.354. https://academic.oup.com/aesa/article/73/4/354/123082. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Grimm, William C. (1983). The Illustrated Book of Trees. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books. pp. 257–259. ISBN 0-8117-2220-1. https://archive.org/details/illustratedbooko0000grim/page/257.

- ↑ Devine, Warren D.; Tyler, Donald D.; Mullen, Michael D.; Houston, Allan E.; Joslin, John D.; Hodges, Donald G.; Tolbert, Virginia R.; Walsh, Marie E. (May 2006). "Conversion from an American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis L.) biomass crop to a no-till corn (Zea mays L.) system: Crop yields and management implications". Soil and Tillage Research 87 (1): 101–111. doi:10.1016/j.still.2005.03.006.

- ↑ Kalm, Pehr (1772) (in en). Travels into North America: containing its natural history, and a circumstantial account of its plantations and agriculture in general, with the civil, ecclesiastical and commercial state of the country, the manners of the inhabitants, and several curious and important remarks on various subjects. London: T. Lowndes. pp. 48-49. ISBN 9780665515002. OCLC 1083889360.

- ↑ Swift, C.E. (October 2011). "Sycamore Anthracnose". Colorado State University Extension. http://www.ext.colostate.edu/pubs/garden/02930.html.

- ↑ Olmert, Michael (1996). Milton's Teeth and Ovid's Umbrella: Curiouser & Curiouser Adventures in History. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 217. ISBN 0-684-80164-7. https://archive.org/details/miltonsteethovid00olme/page/217.

Bibliography

- Fergus, Charles (2002). Trees of Pennsylvania and the Northeast. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books. pp. 162–6. ISBN 978-0-8117-2092-2. OCLC 49493542. https://books.google.com/books?id=4LKBcxNzHZAC&pg=PA162. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

External links

- University of Michigan at Dearborn: Native American Ethnobotany of Platanus occidentalis (American sycamore)

- Cirrusimage.com: American Sycamore — diagnostic photographs and information

- Forestry.about.com: American sycamore - Platanus occidentalis

- Bioimages.vanderbilt.edu: photos of Platanus occidentalis

Wikidata ☰ Q157739 entry

|