Biology:Osteospermum moniliferum

| Osteospermum moniliferum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chrysanthemoides monilifera subsp. rotundata | |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Osteospermum |

| Species: | O. moniliferum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Osteospermum moniliferum L. (1753)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Chrysanthemoides monilifera (L.) Norl. (1943) | |

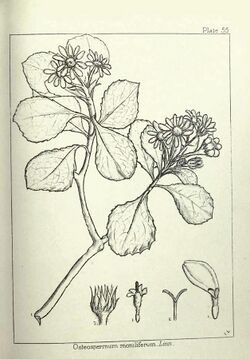

Osteospermum moniliferum (synonym Chrysanthemoides monilifera) is an evergreen flowering shrub or small tree in the daisy family, Asteraceae. It is native to southern Africa, ranging through South Africa and Lesotho to Mozambique and Zimbabwe.[1]

Most subspecies have woolly, dull, serrate, oval leaves, but the subspecies rotundatum has glossy round leaves. Subspecies are known as boneseed and bitou bush in Australasia,[2] or bietou, tick berry, bosluisbessie, or weskusbietou in South Africa.[3] The plant has become a major environmental weed and invasive species in Australia and New Zealand.[2]

Taxonomy

Osteospermum moniliferum has five recognized subspecies:[1]

- Osteospermum moniliferum subsp. canescens (DC.) J.C.Manning & Goldblatt

- Osteospermum moniliferum subsp. moniliferum

- Osteospermum moniliferum subsp. pisiferum (L.) J.C.Manning & Goldblatt

- Osteospermum moniliferum subsp. rotundatum (DC.) J.C.Manning & Goldblatt

- Osteospermum moniliferum subsp. septentrionale (Norl.) J.C.Manning & Goldblatt

Osteospermum moniliferum was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753. It was given the binomial name Chrysanthemoides monilifera in 1943 by Nils Tycho Norlindh.[3] It was one of two species in genus Chrysanthemoides, along with Chrysanthemoides incana (now Osteospermum incanum).[4]

The species name moniliferum comes from the Latin, monile, meaning necklace or collar, referring to the shiny fruit arranged around the flowers like a necklace.[3]

In Australia , O. m. subsp. moniliferum is known by the common name 'boneseed', while O. m. subsp. rotundatum is known by the common name 'bitou bush'.[5] In New Zealand subspecies are not distinguished and O. moniliferum is known simply as 'boneseed'.[6]

Description

Boneseed is a perennial, woody, upright shrub, growing to 3 m (9.8 ft),[7] although occasionally taller.[2] It is a member of the Asteraceae (daisy) family and has showy, bright yellow flowers in swirls of 5–8 'petals' (ray florets) up to 30 mm (1.2 in) in diameter.[7] Fruit are berry-like, spherical at around 8 mm in diameter, and turn dark-brown to black with a bone-coloured seed inside of 6–7 mm diameter. Leaves are 2–6 cm (0.79–2.36 in) long by 1.5–5 cm (0.59–1.97 in) wide, oval tapering to the base with irregularly serrate margins.[2]

Bitou bush can be distinguished from boneseed in part due to its more rounded sprawling habit to 1.5–2 m (4.9–6.6 ft), less noticeably toothy leaf margins and seeds that are egg-like rather than spherical.[2][5][7][8]

Both boneseed and bitou bush hybridise readily, however, so examples of plants demonstrating a fusion of traits is possible.[2]

O. moniliferum has been shown to need pollinators in order to reproduce.[9]

Distribution and habitat

Osteospermum moniliferum occurs naturally in coastal areas of South Africa , reaching into Lesotho, Zimbabwe, and southern Mozambique.[1] Subspecies rotundatum is concentrated along the eastern coast of South Africa from its southern tip through KwaZulu-Natal to southern Mozambique.[4][10] Subspecies moniliferum is concentrated around Cape Town and the Cape Peninsula on South Africa's south western coast, where its native habitats include the Cape Flats Dune Strandveld.[4] Subspecies canescens is native to Kwazulu-Natal, the Northern Provinces, and Free State of South Africa and to Lesotho.[11] Subspecies septentrionale is native to Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and the Northern Provinces.[12]

Invasive species

Australia

In Australia, subspecies rotundatum (bitou bush) has naturalised along the coast of Queensland and New South Wales, while subspecies moniliferum (boneseed) has naturalised along and near the coast in parts of Victoria and South Australia.[5]

New Zealand

In New Zealand O. moniliferum, which is listed on the National Pest Plant Accord, is common in coastal locations throughout the North Island, and can also be found in the South Island in Nelson City, Port Hills (Christchurch) and the Otago Peninsula.[6]

Impact

In Australia, O. moniliferum has been particularly successful in invading natural bushland. In part, this is due to the species' ability to establish on relatively nutrient-poor soils[13] and in areas exposed to salt such as coastlines, as well as the ability of the seeds to germinate readily.[7] Disturbances such as fire can assist O. moniliferum to spread as the plant produces a large amount of seed that can persist in the soil seed bank for 10 years or more, and this reserve in turn enables the species to quickly recolonize a burnt area.[2]

An individual plant can produce 50,000 seeds a year, about 60% of which are viable.[7] Once germinated, seedlings grow vigorously with dense, bushy growth.[13] This lush growth shades out and displaces slower growing native species that might otherwise occupy the same ecological niche.[5] Rapid, vigorous growth also means that O. moniliferum is capable of flowering and setting seed within 12–18 months,[13] making it extremely persistent even in situations where disturbance or regular management activity is common.

Once established, the plant's shallow root system enables it to absorb moisture after light rain before the moisture reaches the roots of more deeply rooted species[7] further limiting opportunities for slower growing species to establish and out-compete O. moniliferum over time. Furthermore, outside of Southern Africa the plant has few local, indigenous pathogens or predators to control its growth[5] also reducing the potential for gaps to emerge that might provide opportunities for other species to reestablish. The net consequence of C. monilifera's growth characteristics is that outside of its natural ecosystem it can ultimately form large, dense, unhealthy stands of a single species with extraordinarily poor biodiversity.

The plant can extend its existing range in a variety of ways. Its fruit is attractive to birds, rabbits, other animals and even some insects such as ants, and because seeds are tough and difficult to digest they will often be dispersed in animal droppings.[13][14] Seeds can also spread on vehicles and equipment, in contaminated soil, in garden waste, along water drainage lines and deliberately by human intervention.[2] Osteospermum moniliferum, unlike many other weed species, is not generally considered to be a problem for agricultural productivity due to its sensitivity to trampling as well as being readily grazed by stock.[7][13][14]

Control

Osteospermum moniliferum is potentially susceptible to a range of control strategies, but Burgman and Lindenmayer recommended that the strategy chosen be responsive to the local situation and available resources.[5] Due to its relatively shallow root system, removal by hand is an ideal method of control.[5][14] Where manual removal is impractical, many common herbicides can be used, in which case the herbicide is commonly applied directly to the wood of the plant via a cut notch, or at the end of a pruned stump.[5] Mechanical removal of O. moniliferum by tractor or other machinery can also be effective, but that process can be extremely indiscriminate, and is only recommended in areas of poor environmental values and minimal erosion risk.[5]

Another way of tackling an infestation is the use of controlled burns, but there are risks associated with that method. Principally, O. moniliferum has higher moisture levels than many Australian indigenous species so, for burns to be effective, a burn of higher than normal intensity is required. That can, in turn, have a detrimental impact on indigenous vegetation which has evolved in response to more frequent, lower-intensity fires. Furthermore, fire can trigger re-germination from the extensive O. moniliferum seed bank, potentially worsening the situation. However, if a program is implemented to monitor and control C. monilifera seedlings following the burn and emerging O. moniliferum seedlings are removed, burning can be extremely effective at exhausting the seed bank and minimising the chances of re-infestation.[5][7]

Various methods of biological control have been attempted, particularly the introduction of insects which are natural enemies of O. moniliferum, such as the bitou tip moth (Comostolopsis germana) and bitou seed fly (Mesoclanis polana).[5] Although they have had some success in controlling bitou bush (ssp. rotundatum) in Australia, to date they have not had similar success in combating boneseed (ssp. moniliferum).[5]

In a study carried out by researchers at the University of New England and published in 2017, it was found that a serious error was made with the introduction of biological control agents into Australia for C. moniliferum ssp. rotundatum. Bitou seed fly (Mesoclanis polana) was introduced based on the naive belief that it is a natural enemy of O. moniliferum. After reviewing many hours of video footage of bitou bush flowers in Northern NSW, researchers at the School of Ecosystem Management[15] found that Mesoclanis polana is actually the most frequent pollinator of O. moniliferum.[9] Because O. moniliferum is a weed of National Significance in Australia, that oversight could potentially be devastating to Australian ecosystems. Much like the introduction of the cane toad to control the population of cane beetles, such a discovery is an important reminder about the importance of thoroughly researching biological control agents before introducing them into new ecosystems.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Osteospermum moniliferum L. Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Blood, K (2001), Environmental weeds: a field guide for SE Australia, Melbourne, Vic., Australia: CH Jerram & Associates, pp. 46–47, 86, ISBN 0-9579086-0-1, OCLC 156877920

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 van Jaarsveld, Ernst (April 2001), Chrysanthemoides monilifera (L.) T.Nord., Kirstenbosch, South Africa: SA National Biodiversity Institute, archived from the original on 2008-08-21, https://web.archive.org/web/20080821133930/http://www.plantzafrica.com/plantcd/chrysanthmon.htm, retrieved 2008-08-04 (Archived by )

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Scott, John K (1996), "Population ecology of Chrysanthemoides monilifera in South Africa: implications for its control in Australia", The Journal of Applied Ecology 33 (6): 1496–1508, doi:10.2307/2404788, ISSN 0021-8901

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 Brougham, KJ; Cherry, H; Downey, PO (2006), Boneseed management manual: current management and control options for boneseed (Chrysanthemoides monilifera ssp. monilifera) in Australia, Sydney, NSW, Australia: Department of Environment and Conservation NSW, pp. 2–5, archived from the original on 2008-01-13, https://web.archive.org/web/20080113232157/http://www.weeds.org.au/WoNS/bitoubush/docs/boneseed_sect4.pdf, retrieved 2008-08-04(Archived by the Wayback Machine: Introduction, Sections 1, 2, 3, , , )

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Roy, Bruce; Popay, Ian; Champion, Paul; James, Trevor; Rahman, Anis (2004), An Illustrated Guide to Common Weeds of New Zealand (2nd ed.), New Zealand Plant Protection Society, ISBN 0-473-09760-5, OCLC 57620998, archived from the original on 2008-10-15, https://web.archive.org/web/20081015043126/http://www.rnzih.org.nz/pages/chrysanthemoidesmonilifera.htm (Archived by )

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 CRC for Australian Weed Management (2003), Weed Management Guide – Boneseed - Chrysanthemoidesmonilifera ssp. monilifera, pp. 1–2, archived from the original on 2008-07-24, https://web.archive.org/web/20080724080421/http://www.weedscrc.org.au/documents/wmg_boneseed.pdf, retrieved 2008-08-04 (Archived by the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ Auld, BA; Medd, RW (1992), Weeds: an illustrated botanical guide to the weeds of Australia (Revised ed.), Melbourne, Vic., Australia: Inkata Press, p. 93, ISBN 0-909605-37-8, OCLC 16581672

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gross, Caroline L.; Whitehead, Joshua D.; Silveira de Souza, Camila; Mackay, David (2017-09-21). "Unsuccessful introduced biocontrol agents can act as pollinators of invasive weeds: Bitou Bush (Chrysanthemoides monilifera ssp. rotundata) as an example". Ecology and Evolution 7 (20): 8643–8656. doi:10.1002/ece3.3441. ISSN 2045-7758. PMID 29075478.

- ↑ Osteospermum moniliferum subsp. rotundatum (DC.) J.C.Manning & Goldblatt. Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ↑ Osteospermum moniliferum subsp. canescens (DC.) J.C.Manning & Goldblatt. Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ↑ Osteospermum moniliferum subsp. septentrionale (Norl.) J.C.Manning & Goldblatt. Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Parsons, WT (1973), Noxious weeds of Victoria, Melbourne, Vic., Australia: Inkata Press, pp. 100–101, ISBN 0-909605-00-9, OCLC 874633

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Emert, S (2001), Gardener's companion to weeds (2nd ed.), Sydney, NSW, Australia: Reed New Holland, p. 100, ISBN 1-876334-77-0, OCLC 52245716

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20171222052955/https://www.une.edu.au/study/study-options/what-to-study/study-areas/animal-related-studies/ecosystem-management

External links

Wikidata ☰ {{{from}}} entry

|