Engineering:Airframe

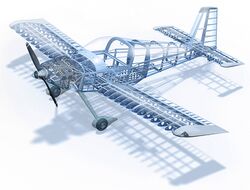

The mechanical structure of an aircraft is known as the airframe.[1] This structure is typically considered to include the fuselage, undercarriage, empennage and wings, and excludes the propulsion system.[2]

Airframe design is a field of aerospace engineering that combines aerodynamics, materials technology and manufacturing methods with a focus on weight, strength and aerodynamic drag, as well as reliability and cost.

History

Modern airframe history began in the United States when a 1903 wood biplane made by Orville and Wilbur Wright showed the potential of fixed-wing designs.

In 1912 the Deperdussin Monocoque pioneered the light, strong and streamlined monocoque fuselage formed of thin plywood layers over a circular frame, achieving 210 km/h (130 mph).[3][4]

First World War

Many early developments were spurred by military needs during World War I. Well known aircraft from that era include the Dutch designer Anthony Fokker's combat aircraft for the German Empire's Luftstreitkräfte, and U.S. Curtiss flying boats and the German/Austrian Taube monoplanes. These used hybrid wood and metal structures.

By the 1915/16 timeframe, the German Luft-Fahrzeug-Gesellschaft firm had devised a fully monocoque all-wood structure with only a skeletal internal frame, using strips of plywood laboriously "wrapped" in a diagonal fashion in up to four layers, around concrete male molds in "left" and "right" halves, known as Wickelrumpf (wrapped-body) construction[5] - this first appeared on the 1916 LFG Roland C.II, and would later be licensed to Pfalz Flugzeugwerke for its D-series biplane fighters.

In 1916 the German Albatros D.III biplane fighters featured semi-monocoque fuselages with load-bearing plywood skin panels glued to longitudinal longerons and bulkheads; it was replaced by the prevalent stressed skin structural configuration as metal replaced wood.[3] Similar methods to the Albatros firm's concept were used by both Hannoversche Waggonfabrik for their light two-seat CL.II through CL.V designs, and by Siemens-Schuckert for their later Siemens-Schuckert D.III and higher-performance D.IV biplane fighter designs. The Albatros D.III construction was of much less complexity than the patented LFG Wickelrumpf concept for their outer skinning.[original research?]

German engineer Hugo Junkers first flew all-metal airframes in 1915 with the all-metal, cantilever-wing, stressed-skin monoplane Junkers J 1 made of steel.[3] It developed further with lighter weight duralumin, invented by Alfred Wilm in Germany before the war; in the airframe of the Junkers D.I of 1918, whose techniques were adopted almost unchanged after the war by both American engineer William Bushnell Stout and Soviet aerospace engineer Andrei Tupolev, proving to be useful for aircraft up to 60 meters in wingspan by the 1930s.

Between World wars

The J 1 of 1915, and the D.I fighter of 1918, were followed in 1919 by the first all-metal transport aircraft, the Junkers F.13 made of Duralumin as the D.I had been; 300 were built, along with the first four-engine, all-metal passenger aircraft, the sole Zeppelin-Staaken E-4/20.[3][4] Commercial aircraft development during the 1920s and 1930s focused on monoplane designs using Radial engines. Some were produced as single copies or in small quantity such as the Spirit of St. Louis flown across the Atlantic by Charles Lindbergh in 1927. William Stout designed the all-metal Ford Trimotors in 1926.[6]

The Hall XFH naval fighter prototype flown in 1929 was the first aircraft with a riveted metal fuselage : an aluminium skin over steel tubing, Hall also pioneered flush rivets and butt joints between skin panels in the Hall PH flying boat also flying in 1929.[3] Based on the Italian Savoia-Marchetti S.56, the 1931 Budd BB-1 Pioneer experimental flying boat was constructed of corrosion-resistant stainless steel assembled with newly developed spot welding by U.S. railcar maker Budd Company.[3]

The original Junkers corrugated duralumin-covered airframe philosophy culminated in the 1932-origin Junkers Ju 52 trimotor airliner, used throughout World War II by the Nazi German Luftwaffe for transport and paratroop needs. Andrei Tupolev's designs in Joseph Stalin 's Soviet Union designed a series of all-metal aircraft of steadily increasing size culminating in the largest aircraft of its era, the eight-engined Tupolev ANT-20 in 1934, and Donald Douglas' firms developed the iconic Douglas DC-3 twin-engined airliner in 1936.[7] They were among the most successful designs to emerge from the era through the use of all-metal airframes.

In 1937, the Lockheed XC-35 was specifically constructed with cabin pressurization to undergo extensive high-altitude flight tests, paving the way for the Boeing 307 Stratoliner, which would be the first aircraft with a pressurized cabin to enter commercial service.[4]

Second World War

During World War II, military needs again dominated airframe designs. Among the best known were the US C-47 Skytrain, B-17 Flying Fortress, B-25 Mitchell and P-38 Lightning, and British Vickers Wellington that used a geodesic construction method, and Avro Lancaster, all revamps of original designs from the 1930s. The first jets were produced during the war but not made in large quantity.

Due to wartime scarcity of aluminium, the de Havilland Mosquito fighter-bomber was built from wood—plywood facings bonded to a balsawood core and formed using molds to produce monocoque structures, leading to the development of metal-to-metal bonding used later for the de Havilland Comet and Fokker F27 and F28.[3]

Postwar

Postwar commercial airframe design focused on airliners, on turboprop engines, and then on jet engines. The generally higher speeds and tensile stresses of turboprops and jets were major challenges.[8] Newly developed aluminium alloys with copper, magnesium and zinc were critical to these designs.[9]

Flown in 1952 and designed to cruise at Mach 2 where skin friction required its heat resistance, the Douglas X-3 Stiletto was the first titanium aircraft but it was underpowered and barely supersonic; the Mach 3.2 Lockheed A-12 and SR-71 were also mainly titanium, as was the cancelled Boeing 2707 Mach 2.7 supersonic transport.[3]

Because heat-resistant titanium is hard to weld and difficult to work with, welded nickel steel was used for the Mach 2.8 Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-25 fighter, first flown in 1964; and the Mach 3.1 North American XB-70 Valkyrie used brazed stainless steel honeycomb panels and titanium but was cancelled by the time it flew in 1964.[3]

A computer-aided design system was developed in 1969 for the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle, which first flew in 1974 alongside the Grumman F-14 Tomcat and both used boron fiber composites in the tails; less expensive carbon fiber reinforced polymer were used for wing skins on the McDonnell Douglas AV-8B Harrier II, F/A-18 Hornet and Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit.[3]

Modern era

Airbus and Boeing are the dominant assemblers of large jet airliners while ATR, Bombardier and Embraer lead the regional airliner market; many manufacturers produce airframe components.[relevant? ]

The vertical stabilizer of the Airbus A310-300, first flown in 1985, was the first carbon-fiber primary structure used in a commercial aircraft; composites are increasingly used since in Airbus airliners: the horizontal stabilizer of the A320 in 1987 and A330/A340 in 1994, and the center wing-box and aft fuselage of the A380 in 2005.[3]

The Cirrus SR20, type certificated in 1998, was the first widely produced general aviation aircraft manufactured with all-composite construction, followed by several other light aircraft in the 2000s.[10]

The Boeing 787, first flown in 2009, was the first commercial aircraft with 50% of its structure weight made of carbon-fiber composites, along with 20% aluminium and 15% titanium: the material allows for a lower-drag, higher wing aspect ratio and higher cabin pressurization; the competing Airbus A350, flown in 2013, is 53% carbon-fiber by structure weight.[3] It has a one-piece carbon fiber fuselage, said to replace "1,200 sheets of aluminium and 40,000 rivets."[11]

The 2013 Bombardier CSeries have a dry-fiber resin transfer infusion wing with a lightweight aluminium-lithium alloy fuselage for damage resistance and repairability, a combination which could be used for future narrow-body aircraft.[3] In 2016, the Cirrus Vision SF50 became the first certified light jet made entirely from carbon-fiber composites.

In February 2017, Airbus installed a 3D printing machine for titanium aircraft structural parts using electron beam additive manufacturing from Sciaky, Inc.[12]

| Material | B747 | B767 | B757 | B777 | B787 | A300B4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminium | 81% | 80% | 78% | 70% | 20% | 77% |

| Steel | 13% | 14% | 12% | 11% | 10% | 12% |

| Titanium | 4% | 2% | 6% | 7% | 15% | 4% |

| Composites | 1% | 3% | 3% | 11% | 50% | 4% |

| Other | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 5% | 3% |

Safety

Airframe production has become an exacting process. Manufacturers operate under strict quality control and government regulations. Departures from established standards become objects of major concern.[14]

A landmark in aeronautical design, the world's first jet airliner, the de Havilland Comet, first flew in 1949. Early models suffered from catastrophic airframe metal fatigue, causing a series of widely publicised accidents. The Royal Aircraft Establishment investigation at Farnborough Airport founded the science of aircraft crash reconstruction. After 3000 pressurisation cycles in a specially constructed pressure chamber, airframe failure was found to be due to stress concentration, a consequence of the square shaped windows. The windows had been engineered to be glued and riveted, but had been punch riveted only. Unlike drill riveting, the imperfect nature of the hole created by punch riveting may cause the start of fatigue cracks around the rivet.

The Lockheed L-188 Electra turboprop, first flown in 1957 became a costly lesson in controlling oscillation and planning around metal fatigue. Its 1959 crash of Braniff Flight 542 showed the difficulties that the airframe industry and its airline customers can experience when adopting new technology.

The incident bears comparison with the Airbus A300 crash on takeoff of the American Airlines Flight 587 in 2001, after its vertical stabilizer broke away from the fuselage, called attention to operation, maintenance and design issues involving composite materials that are used in many recent airframes.[15][16][17] The A300 had experienced other structural problems but none of this magnitude.

See also

- Longeron

- Former

- Chord (aeronautics)

- Aircraft fairing

- Vertical stabilizer

References

- ↑ Wragg, David W. (1974). A Dictionary of Aviation (1st American ed.). New York: Frederick Fell, Inc.. p. 22. ISBN 0-85045-163-9.

- ↑ "FAA Definitions". http://www.faa-aircraft-certification.com/faa-definitions.html.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Graham Warwick (Nov 21, 2016). "Designs That Changed The Way Aircraft Are Built". Aviation Week & Space Technology. http://aviationweek.com/commercial-aviation/designs-changed-way-aircraft-are-built.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Richard P. Hallion (July 2008). "Airplanes that Transformed Aviation". Air & space magazine (Smithsonian). http://www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/airplanes-that-transformed-aviation-46502830/?all.

- ↑ Wagner, Ray; Nowarra, Heinz (1971). German Combat Planes: A Comprehensive Survey and History of the Development of German Military Aircraft from 1914 to 1945. New York: Doubleday. pp. 75 & 76.

- ↑ David A. Weiss (1996). The Saga of the Tin Goose. Cumberland Enterprises.

- ↑ Peter M. Bowers (1986). The DC-3: 50 Years of Legendary Flight. Tab Books.

- ↑ Charles D. Bright (1978). The Jet Makers: the Aerospace Industry from 1945 to 1972. Regents Press of Kansas. http://www.generalatomic.com/jetmakers/index.html.

- ↑ Aircraft and Aerospace Applications. INI International. 2005. http://www.key-to-metals.com/PrintArticle.asp?ID=96.

- ↑ "Top 100 Airplanes:Platinum Edition". Flying: p. 11. November 11, 2013. http://www.flyingmag.com/photo-gallery/photos/top-100-airplanes-platinum-edition?pnid=44581.

- ↑ Leslie Wayne (May 7, 2006). "Boeing Bets the House on Its 787 Dreamliner". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/07/business/yourmoney/07boeing.html.

- ↑ Graham Warwick (Jan 11, 2017). "Airbus To 3-D Print Airframe Structures". Aviation Week & Space Technology. http://aviationweek.com/technology/airbus-3-d-print-airframe-structures.

- ↑ Woidasky, Jörg; Klinke, Christian; Jeanvré, Sebastian (5 November 2017). "Materials Stock of the Civilian Aircraft Fleet". Recycling 2 (4): 21. doi:10.3390/recycling2040021.

- ↑ Florence Graves and Sara K. Goo (Apr 17, 2006). "Boeing Parts and Rules Bent, Whistle-Blowers Say". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/04/16/AR2006041600803.html.

- ↑ Todd Curtis (2002). "Investigation of the Crash of American Airlines Flight 587". AirSafe.com. http://www.airsafe.com/events/aa587.htm.

- ↑ James H. Williams Jr. (2002). "Flight 587". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/jhwill/www/Flight587.html.

- ↑ Sara Kehaulani Goo (Oct 27, 2004). "NTSB Cites Pilot Error in 2001 N.Y. Crash". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A63850-2004Oct26.html.

Further reading

- Michael Gubisch (9 July 2018). "Analysis: Are composite airframes feasible for narrowbodies?". Flightglobal. https://www.flightglobal.com/news/articles/analysis-are-composite-airframes-feasible-for-narro-449415/.

|