Philosophy:Australian modernism

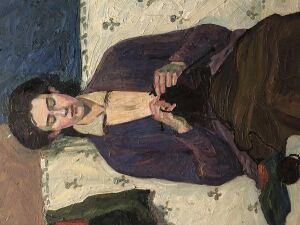

| The Sock Knitter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Grace Cossington Smith |

| Year | 1915 |

| Medium | oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 61.8 cm × 51.2 cm (24.3 in × 20.2 in) |

| Location | Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney |

Australian modernism, similar to European and American modernism, was a social, political and cultural movement that was a reaction to rampant industrialisation, associated moral panic of modernity and the death and trauma of the World Wars.[1]

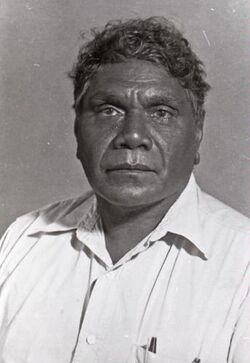

In art, the movement included female artists who reacted against the male-dominated art style of naturalism.[2] It is also important to note the presence of Indigenous Australian art during this time. Indigenous modernism refers to the unique experience of modernity of Aboriginal Australians, that is vastly different to the white Australians' experience of modernity. Albert Namatjira was the first Indigenous modernist to be recognised. It was not until the 1960s and 1970s that scholars began to call Indigenous art modern, as there was a distinction made between modern and contemporary Indigenous art to traditional Indigenous art.[3]

Modernist architecture was also expressed in many buildings in Australia. Modernist architects such as Harry Seidler, Sydney Ancher, Robin Boyd, Roy Grounds and John Morphett were some of the best known names, and the iconic Adelaide Festival Centre is a fine example of modernist architecture.

The mainstream modernist movement began in Australia approximately in 1914 and continued until 1948.[4] Throughout these years tensions continued between the conservative and the avant-garde schools of thought. The years following the Second World War is when Australian modernism gained notability in the art world of Australia. Nationalistic pastoral painting of the Australian landscape were superseded by abstracted, colourful distorted images of modernist works. After the World Wars the dynamics of society in Australia and overseas changed dramatically, causing increased acceptance and attraction towards modernism. Social and political unrest continued due to the devastation of war and increased immigration occurred. This led to a number of European artists moving to Australia, which contributed to the introduction of further art styles, such as surrealism, social realism and expressionism. Additionally, continued technological progress in the later 20th century contributed to an increase in cubism and print making.[1]

History

Beginnings

Modernism reached Australia significantly later than in Europe and America. The high art scene in Australia in the late 19th century and early 20th century predominantly included pastoral paintings, which refer to art which depicts the landscapes and farms of Australia.[2] It wasn't until the early 1900s when there was an influx of female artists who joined their male counterparts to study art in Paris that Modernist ideologies begin to reach Australia.[5] In 1913 the Sydney artist Norah Simpson returned from Europe where she had been studying art in Paris and London at the Westminster School of Art[6] she brought reproductions of leading modernists artists works such as Henri Matisse, Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, etc.[7] She shows these works to her art teacher Antionio Dattilo-Rubbo as well as her fellow pupils at his art school which include notably Australian Modernists such as Grace Cossington-Smith.[7]

Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo was an Italian-born artist and teacher. In 1906 he also studied art in Europe including England, France and Italy, observing art exhibitions and art schools which developed his passion for modern art.[8] Dattilo-Rubbons, passion for modern art and the reproductions brought by Simpson significantly contributed to the development of Modernism in Australia.[1] Notably, as the first Australian Modernist painting, The Sock Knitter by 1914 was created out of Dattilo-Rubbons art school by Norah Simpson's fellow pupil Grace Cossington-Smith.[7]

In Melbourne and opposed to both Impressionism and modernism were the Tonalists, identified, and ridiculed by the mainstream, as 'misty moderns,' led by Max Meldrum from 1916, who propounded a 'scientific' method. One of his disciples Clarice Beckett, abandoned his strictures to give prominence to colour in form, and through the 1920s and early 1930s, independently practiced a reductionism verging on abstraction now recognised as early examples in Victoria of the Modern.[9][10]

International influence

After the initial introduction of modernism in Australia in 1914, the movement steadily grew in popularity, with more artists adopting the skills and techniques of Modernism. In the 1920s and 1930s more artists alike Norah Simpson travelled overseas namely to Paris to study. These artists were exposed to an arrange of art teachers who taught them about various new art styles. These artists who travelled to Europe at this time included Grace Cossington-Smith, Anne Dangar and Dorrit Black, who learnt about Cubist theories and methods by their teacher Andre Lhote.[11] These female modernists learnt about cubism in France and brought back these techniques and employed these techniques to the Australian context, For example Dorriet Black's 1932 lino print, Noctornal depicts the Sydney street Wynyard with simplistic forms that are indicative of cubism. Many more art styles and movements emerged from the 1920s and 1930s. Modernism was expressed and accepted differently in different capitals cities of Australia. There were a higher portion of Modernist artists living and working in Sydney, including Margaret Preston and Grace Crowley, so Sydney was a hotspot of Modern art. The key art style and element, however, was design. In Melbourne art was significantly more conceptual and focused on moral panic. The environment in Melbourne at this time was less accepting of Modern art. Adelaide however, approached Modernism completely differently again. Surrealism was a key element of art that came out of Adelaide.[4]

World War influence

In the 1930s across the world including Australia there was increased political and economic uncertainty due to the end of the first World War and the growing tensions that would eventually lead to the Second World War. This social uncertainty meant that the growing Modernist movement became increasingly more appealing to artists which caused an increase in popularity. As the popularity of Modernism steadily continued tensions between the conservative and modern school of thoughts began. However, naturalism (also known as realism) remained the dominant high art culture of Australia.[2]

The end of the World Wars contributed to further acceptance of this movement. In between the first and second World Wars there was a lot of uncertainty social and political unrest which fuelled many modernist artists. Naturalistic art prospered as the national image until the end of the Second World War where even more social and political unrest existed.[2]

After the World War II there was increased public concern about Modernity, industrialisation of modern life which caused increased associations with Modernist Ideas. There was also increased human movement and immigration to Australia due to the death and destruction caused by the Wars in Europe, as compared to Europe there was no damage to infrastructure, homes and towns in Australia. This changing the dynamic's of the Australian way of life. This human movement contributed to greater mixtures of people and life experience meant that the idea of nationalism changed and the image of identity changed this included the national art image. Therefore Modernism became more appealing and widely accepted in the 1940s.These international immigrants changed the dynamics of the Art world of Australia through the introduction of different styles of modern art. These styles included surrealism, social realism and expressionism.[12]

Main art styles and types

Still life and interiors

The Australian female Modernists employed avant-garde techniques and skill to their art however much of the subject matter was quite traditional and not provocative like their European counterparts.[13] This traditionalistic subject matter included Still life's and Interiors which often included objects that were found their own homes and gardens. Although, this kind of subject matter was somewhat repetitive and consequently limited was also quite fluid and free for these women. Australian society placed many restrictions on females as a result of intense patriarchal stereotypes, these Interiors and Still life paintings gave these woman a space to express their own experience which was given less priority in Society. Grace Cossington-Smith 1956 work The Window is an example of such Modernist interior paintings.

Additionally, it is suggested that homosexual men at this time valued from Modernist still lifes and interiors as the national pastoral paintings likewise excluded non-heterosexual men.[7]

Etching/print making

The modernisation of technologies of the 20th century contributed to the development of new ways of producing and creating art through the use of advanced technologies such as etching and print making.[14] The Australian Modernists created multiple different forms of print making. These included coloured and black and white Etchings, Lino printing and relief painting. The artist Dorrit Black created these coloured and black and white lino prints which used cubist imagery of her surroundings.

Cubism

The key and earliest cubists in Australia include Dorriet Black, Anne Dangar and Grace Crowley, who were all students of the French teacher Andre Lhote, who was a salon cubist.[15] Grace Crowley began a teacher in Sydney and taught her ideas of geometric cubist art to further generations and became a significant figure in the modernist and notably cubist style.[16]

Surrealism

Surrealism was first developed in France in the 1920s, and this style did not reach Australia until the 1930s. The international surrealist exhibition held in Burlington Galleries in London in 1936 is seemingly the cause for surrealism to reach Australia. Artist Peter Purves Smith was living in London at this time and attended this exhibition. The influence of this exhibition on his art practice is evident through the "strange figurative distortion"[17] that pervades his works including New York 1936.

In 1939 the first major exhibition that presented surrealist artists and works was showcased. This exhibition was held in the National Gallery of Victoria in 1939 by the Contemporary Art Society. This public received these works well due to the associated fear of the outbreak of war the images within these paintings resonated with the public.[17]

Indigenous modernist art

The term "Indigenous Modernism" is a contentious term due to problematic ideas and perceptions around Indigenous Australian art and imagery in the 20th century by westerners. Many modernists in Australia and in Europe employed Indigenous imagery and or artefacts in their works, as there was an increase interest due to the idea of social evolution, which suggests that the "primitive" cultures hold the key to progress.[18] Artists since have stolen these iconographies since the beginning of Modernism, including the Australian artist Margaret Preston.[19]

Some Indigenous artists accept this association and inclusion in this art period whereas others do not. Therefore, there are multi-dimensional definitions of Indigenous Modernism. Indigenous Modernism has been distinguished as being the unique aesthetic representation of Indigenous Peoples experiences of Modernism which is vastly different to Eurocentric experiences. This relates to timeline as well as physical experiences. This definition assumes and accepts that all types of Indigenous art that being traditional or contemporary is inherently Modernist in nature as all this art for Indigenous Peoples depicts their experiences with Modernity.[3]

Comparatively, other schools of thought state that Modernism as a whole is suppressive to Indigenous Culture and art. It is said that Modernism and modernity are so tightly linked that as modernity caused the death and destruction of cultures other than western which Include Indigenous that Modernism additionally contributed to this destruction of culture. Therefore, on this basis resist the term 'Indigenous Modernism'. This reluctance also stems from not wanting to associate the distorted images that exist in traditional body painting and ground drawings with the "aesthetic abstraction" (73) [20] of western Modernism.[20]

Despite this complex relationship between Indigenous Culture and Modernism there some famous Indigenous 'modernists' artists and movements such as Albert Namatjira and his water colour landscapes which started the Hermannsburg group [21] and the Western Desert Aboriginal art.

Albert Namatjira

Albert Namatjira is an Indigenous artist born in Hermannsburg in central Australia, who painted water-colour landscapes. He is one of the most well-known Modernist Indigenous artists in the western sense of the word.[3] His style was heavily influenced by the artists Rex Battarbee and John Gardner. His first exhibition in Melbourne in 1938 sold out, and his work became very popular. He continued his legacy by sharing his skills with other men who lived around him, inspiring a whole new generation of artists.[citation needed]

Western Desert Art Movement

The Indigenous western acrylic desert art movement began approximately in 1971[22] in Papunya in the Australian outback. This town is home to multiple different groups of Aboriginal Australians who speak different languages, including Pintupi, Luritja, Warlpiri, Arrerrnte, and Anmatyerre, making up the Western Desert cultural bloc. This town was created as a result of an attempted assimilation project by the Government in the 1960s; the peoples had no cultural association with this land, being forcibly moved there. Geoffrey Bardon, a teacher who was sent to this town, helped the cultural dissonance that existed in this town. Initially, he began to teach the children to paint things that related to their world and then encouraged elders of the town to paint murals using acrylic of their dreamtime stories rather than in the desert sand.[23]

This style of art was used to mobilise Indigenous communities and protest for Indigenous rights by the Papunya people. They hoped that their art would showcase to wider society of their culture, connection and claim to the land. Their art gained a lot of attention by wider society, their art was bought, commissioned and showcased in exhibitions. This recognition meant that the Indigenous culture was placed in the forefront of mainstream society more than ever.[22]

Modernist architecture

Well-known modernist architects in Australia include Harry Seidler AC OBE, Sydney Ancher, Arthur Baldwinson, Robin Boyd, and Walter Bunning CMG, who were known for their modernist houses.[24]

Sir Roy Grounds designed the Australian Academy of Science in Canberra in 1959[25]

In Adelaide, John Morphett, at the time with the firm Hassell and Partners was chief architect for the Adelaide Festival Centre.[26] There were also a number churches, university buildings and houses built in modernist style.[27]

See also

- Modernist art

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Australian art :: Learn more :: Discover art :: Art Gallery NSW". https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/discover-art/learn-more/australian-art/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Hunt, Jane (2003). "Victors and Victims? Men, Women, Modernism and art in Australia". Journal of Australian Studies 27 (80): 65–75. doi:10.1080/14443050309387913.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 McLean, Ian (9 May 2016). "Aboriginal Modernism". Routledge Enyclipedia of Modernism. doi:10.4324/9781135000356-REM178-1. https://www.rem.routledge.com/articles/indigenous-modernisms.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Burke, Janine (2007-02-23). "Modernism & Australia: documents on art, design and architecture 1917-1967" (in en). https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/modernism-and-australia-documents-on-art-design-and-architecture-1917-1967-20070224-gdpjde.html.

- ↑ Genoni, Paul (2004). "Art is the Windoepane". Novels of Australian Women and Modernim in Inter-War Europe: 159–170. https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/JASAL/article/viewFile/9683/9571.

- ↑ Hoorne, Janette (1992). "Misogyny and modernist painting in Australia: How male critics made modernism their own". Journal of Australian Studies 16 (32): 7–18. doi:10.1080/14443059209387082.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Butler, Rex (2010). "French, Floral and Female: A History of UnAustralian Art 1900-1930". Electronic Melbourne Art Journal 1.

- ↑ Oakley, Carmel, "Rubbo, Antonio Salvatore Dattilo (1870–1955)", Australian Dictionary of Biography (National Centre of Biography, Australian National University), http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/rubbo-antonio-salvatore-dattilo-8291, retrieved 2020-02-08

- ↑ Borlase, Nancy (8 December 1979). "In Hostility". The Sydney Morning Herald: pp. 16.

- ↑ Cosic, Miriam (1 April 2021). "Clarice Beckett: The Present Moment. Art Gallery of South Australia, until May 16". The Monthly: pp. 65.

- ↑ Howell, Catherine (2010). "Changing Perspectives on Modernism in Australia: Cubism and Australian Art" (in en). Modernism/Modernity 17 (4): 925–933. doi:10.1353/mod.2010.0039. ISSN 1080-6601.

- ↑ "Australian art :: Learn more :: Discover art :: Art Gallery NSW". https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/discover-art/learn-more/australian-art/.

- ↑ Bulter, Rex (2010). "French, Floral and Female: A History of UnAustralian Art 1900-1930 (part 1)". Electronic Melbourne Art Journal 5. ProQuest 1159208513.

- ↑ "20th-century Australian art: Modern impressions". https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/artsets/sylx9d.

- ↑ Howel, Catherine (2010). Changing Perspectives on Modernism in Australia; Cubism and Australian Art. Johns Hopkins University Press DOI. pp. 3–5.

- ↑ "20th-century Australian art: Cubism in Australia". https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/artsets/uj9ej3.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Collections: The Agapitos/Wilson collection of Australian Surrealism". https://nga.gov.au/australiansurrealism/.

- ↑ Mclean, Ian. "Contemporaneous Traditions: The World in Indigenous Art/ Indigenous Art in the World". http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p245111/pdf/Ian-Mclean.pdf.

- ↑ "Margaret Preston | NGV". https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/exhibition/margaret-preston/.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Mclean, Ian (2008). "Aboriginal Modernism in Central Australia" (in en). Exiles, Diasporas & Strangers: 72–95. https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/aboriginal-modernism-in-central-australia.

- ↑ "Albert Namatjira & the Hermannsburg School" (in en-US). https://japingkaaboriginalart.com/articles/albert-namatjira-the-hermannsburg-school/.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Ginsburg, Faye (2006). "A History of Aboriginal Futures". Critique of Anthropology 26: 27–45. doi:10.1177/0308275X06061482.

- ↑ Wroth, David. "Early Influence of Geoffrey Bardon on Australian Aboriginal Art". https://japingkaaboriginalart.com/articles/geoffrey-bardon-influence/.

- ↑ "Australia's first true Modernist architect". 22 August 2017. https://www.modernhouse.co/who-is-australias-first-true-modernist-architect/.

- ↑ Miletic, Branko, ed (14 October 2020). "Australia's best mid-20th century modern architecture". https://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/features/list/best-australian-mid-century-modern-architecture.

- ↑ Harrison, Stuart (20 November 2019). "South Australian modernism exhibition a study in modesty". https://architectureau.com/articles/sa-modernism-exhibition-a-study-in-modesty/.

- ↑ Keen, Suzie (10 December 2019). "Modernist Adelaide: How mid-century design shaped our city". https://indaily.com.au/news/local/2019/12/10/modernist-adelaide-how-mid-century-design-shaped-our-city/.

|