Philosophy:Theosophical Society in Costa Rica

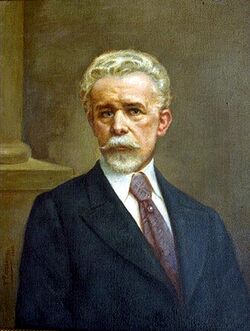

The Theosophical Society in Costa Rica was the local branch of the world Theosophical Society based in Adyar, India. It was founded on March 27, 1904 in the city of San José, and like Freemasonry in Costa Rica, it was the first in Central America, 1 it was introduced by the Spanish painter based in Costa Rica Tomás Povedano who began in Spanish theosophy.[1] Its first lodge or branch was the Virya Branch, which published a magazine of the same name, currently it has four branches or lodges; Virya, Shakti Lodge, Dharma Lodge and HPB.[2]

Theosophy in Costa Rica had an important cultural and intellectual roots in the country, rapidly becoming popular among important sectors of the country's intellectual elite and significantly influencing different political, cultural and artistic movements. Some of the prominent Costa Ricans who have been Theosophists include the aforementioned Povedano, the poet Roberto Brenes Mesén, the writer and first lady María Fernández Le Cappellain, the poet Eunice Odio, the educator Omar Dengo and even the President of the Republic Julio Acosta García.[2][3][4]

History

The Theosophical Society was founded in March 1904 by Tomás Povedano and the Bertod family of Cuban origin, although previously Jorge Madriz, son of the former president and Freemason José María Castro Madriz, had been an adept of theosophy. It quickly became popular among broad sectors of the intellectual population of the country, soon calling the attention of the Catholic Church in Costa Rica, generating angry controversies in the press where both sides clashed with articles of attack and response. On May 8, 1912, the first Theosophical Center located on the Paseo de las Damas in the capital city and on whose date the death of Blavastky and the birth of Buddha were commemorated, however, the building would be burned by a Catholic extremist a year later. In 1917 the then Archbishop of San José Juan Gaspar Stork Werth excommunicated all members of the Theosophical Society.[5][1]

In 1916, the International Bank of Costa Rica, which then worked as a coin minter and was chaired by the theosophist Walter J. Field (Povedano's son-in-law), printed a ten-colón banknote with Field's image showing the theosophical symbol on the flap of his jacket, which caused a scandal by the Church. President Alfredo González Flores received pressure from the Church and his religious family to take action, but he was also faced with influential theosophists such as María Fernández, wife of his Minister of War Federico Tinoco, although finally González opted for the anti-theosophical side.[5]

It is debated how much these disagreements between Catholics and Theosophists had to do with the enmity that arose between González and Tinoco. On January 27, 1917, Tinoco would carry out a coup against González, aided by his brother, the military man José Joaquín Tinoco Granados, and under the Tinoco dictatorship, several theosophists would form part of his government, including Roberto Brenes Mesén. However, it would be another theophist who would lead the anti-Tinoquist opposition and who was González's chancellor, Julio Acosta.

Overthrown Tinoco after the Sapoá Revolution, the 1919 student civic movement and other social uprisings, Acosta participates in the following elections. His status as a Mason and theosophist raised suspicions among the Church, but his triumph was assured by having led the anti-Tinoquist struggle and he won by a wide margin.[6]

On October 6, 1933, Jiddu Krishnamurti visited Costa Rica as part of a tour of Latin America that included Brazil , Uruguay and Mexico. Krishnamurti was enthusiastically received by most of the local theosophical community, although by that time there were differences between Theosophists who denied the messianic character of Krishnamurti and those who supported the thesis of Annie Besant, nevertheless most of the Costa Rican Theosophists were of the second group.[5] The visit did not go unnoticed by the Catholic Church, which reacted furiously.[5]

After these turbulent periods, the presence of the Theosophical Society stabilized, integrating without major controversy into Costa Rican society. Currently, the Costa Rican Theosophical Society is part of the Inter-American Theosophical Federation like most American theosophical societies, and holds public lectures and free courses every week.[2]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Rodríguez Dobles, Esteban (December 2010-Abril 2011). "Conflictos en torno a las representaciones sociales del alma y los milagros. La confrontación entre la Iglesia Católica y la Sociedad Teosófica en Costa Rica (1904-1917)". Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña Vol. 2, Nº 2. ISSN 1659-4223.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Villalobos Salgado, Jorge Andrés. "Teoosfía". Prolades.

- ↑ Introvigne, Massimo (2006). "New Acropolis". in Clarke, Peter B.. Encyclopedia of new religious movements. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 441–442. ISBN 9-78-0-415-26707-6.

- ↑ Introvigne, Massimo (23 November 1997). "Démissionnaires, partants ordinaires et apostats: une étude quantitative auprès d'anciens membres de Nouvelle Acropole en France". CESNUR. https://www.cesnur.org/testi/Acropole.htm.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "El hechizo de Krishnamurti en Costa Rica". La Nación. 2 July 2007. https://www.nacion.com/viva/cultura/el-hechizo-de-krishnamurti-en-costa-rica/NAWQ76I4WRBGFO7JKKHVZCXE2E/story/. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ↑ Porras, Carlos (2 July 2017). "Julio Acosta García, el presidente que viajaba en bus.". mislibrosconnotas.blogspot.com. https://mislibrosconnotas.blogspot.com/2017/07/el-presidente-julio-acosta-garcia.html. Retrieved 16 December 2018.