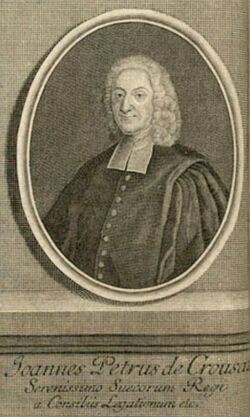

Biography:Jean-Pierre de Crousaz

Jean-Pierre de Crousaz | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 April 1663 Lausanne |

| Died | 22 March 1750 (aged 86) Lausanne |

| Nationality | Swiss |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

Jean-Pierre de Crousaz (13 April 1663 – 22 March 1750) was a Switzerland theologian and philosopher. He is now remembered more for his letters of commentary than his formal works.

Life

De Crousaz was born in Lausanne. He was a many-sided man, whose numerous works on many subjects had a great vogue in their day, but are now forgotten. He has been described as an initiateur plutôt qu'un créateur (an initiator rather than a creator), chiefly because he introduced the philosophy of Descartes to Lausanne in opposition to the reigning Aristotelianism, and also as a Calvinist pedant (for he was a pastor) of the French abbés of the 18th century.[1]

He studied in Geneva, Leiden, and Paris, before becoming professor of philosophy and mathematics at the academy of Lausanne in 1700. He was rector of the academy four times before 1724, when theological disputes led him to accept a chair of philosophy and mathematics at Gröningen. In 1726 he was appointed governor to the young prince Frederick of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel), and in 1735 returned to Lausanne with a good pension. In 1737 he was reinstated in his old chair, which he retained to his death.[1]

Edward Gibbon, describing his first stay at Lausanne (1752–1755), writes in his autobiography, "The logic of de Crousaz had prepared me to engage with his master Locke and his antagonist Bayle".[1]

Works

The most important of his works are:

- Nouvel Essai de logique (1712)

- Géométrie des lignes et des surfaces rectilignes et circulaires (1712)

- Traité du beau (1714)

- Examen du traité de la liberté de penser d'Antoine Collins (1718)

- De l'éducation des enfants (1722, dedicated to the then Princess of Wales)

- Examen du pyrrhonisme ancien et moderne (1733, an attack chiefly on Bayle)

- Examen de l'essai de M. Pope sur l'homme (1737, an attack on the Leibnitzian theory of Pope's poem Essay on Man)

- Logique (6 vols., 1741)

- De l'ésprit humain (1741)

- Réflexions sur l'ouvrage intitulé: La Belle Wolfienne (1743)[2]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Chisholm 1911, p. 512.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911.

References