Social:Soyombo alphabet

| Soyombo script 𑪁𑩕𑩻𑩕𑪐𑩲𑩕 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Abugida

|

| Languages | Mongolian, Tibetan, Sanskrit |

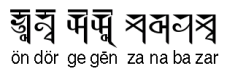

| Creator | Zanabazar, 1686 |

Time period | 17th century–18th century |

Parent systems | Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Soyo, 329 |

Unicode alias | Soyombo |

| |

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

The Soyombo alphabet (Mongolian: Соёмбо бичиг, Soyombo biçig) is an abugida developed by the monk and scholar Zanabazar in 1686 to write Mongolian. It can also be used to write Tibetan and Sanskrit.

A special character of the script, the Soyombo symbol, became a national symbol of Mongolia, and has appeared on the national flag since 1921, and on the Emblem of Mongolia since 1960, as well as money, stamps, etc.

Creation

The Soyombo script was created as the fourth Mongolian script, only 38 years after the invention of the Clear script. The name of the script alludes to this story. It is derived from the Sanskrit word Svayambhu "self-created".

The syllabic system in fact appears to be based on Devanagari, while the base shape of the letters is derived from the Ranjana alphabet. Details of individual characters resemble traditional Mongolian alphabets and the Old Turkic alphabet.

It is unclear whether Zanabazar designed the Soyombo symbol himself or if it had existed beforehand.

Use

The eastern Mongols used the script primarily as a ceremonial and decorative script. Zanabazar had created it for the translation of Buddhist texts from Sanskrit or Tibetan, and both he and his students used it extensively for that purpose.

As it was much too complicated to be adopted as an everyday script, its use is practically nonexistent today. Aside from historical texts, it can usually be found in temple inscriptions. It also has some relevance to linguistic research, because it reflects certain developments in the Mongolian language, such as that of long vowels.

Form

The Soyombo script was the first Mongolian script to be written horizontally from left to right, in contrast to earlier scripts that had been written vertically. As in the Tibetan and Devanagari scripts, the signs are suspended below a horizontal line, giving each line of text a visible "backbone".

The two variations of the Soyombo symbol are used as special characters to mark the start and end of a text. Two of its elements (the upper triangle and the right vertical bar) form the angular base frame for the other characters.

Within this frame, the syllables are composed of one to three elements. The first consonant is placed high within the angle. The vowel is given by a mark above the frame, except for u and ü which are marked in the low center. A second consonant is specified by a small mark, appended to the inside of the vertical bar, pushing any u or ü mark to the left side. A short oblique hook at the bottom of the vertical bar marks a long vowel. There is also a curved or jagged mark to the right of the vertical bar for the two diphthongs.

Alphabet

The first character of the alphabet represents a syllable starting with a short a. Syllables starting with other vowels are constructed by adding a vowel mark to the same base character. All remaining base characters represent syllables starting with a consonant. A starting consonant without a vowel mark implies a following a.

In theory, 20 consonants and 14 vowels would result in almost 4,000 combinations, but not all of those actually occur in Mongolian. There are additional base characters and marks for writing Tibetan or Sanskrit, and some of the symbols used in these two languages will also not be used in Mongolian.

Mongolian

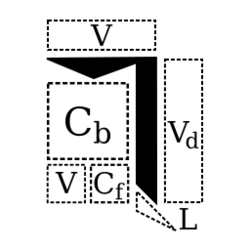

A syllable in Mongolian can contain the following elements: consonant or vocal carrier (Cb), vowel (V), length marker (L), diphthong marker (Vd) and a final consonant Cf).[1]

Vowels

Mongolian uses seven vowels, all of which have a short and a long form. The long form is indicated with the length mark:

| 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | ||

| a | i | e | ü | u | o | ö |

| 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | ||

| ā | ī | ē | ǖ | ū | ō | ȫ |

Diphthong markers are used with other vowel signs to represent diphthongs in Mongolian:

| -i | -u |

Consonants

| 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | ||

| ga/ɣa | ka/qa | ŋa | ǰa | ča | ña | da | ta | na | ba |

| 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | ||

| pa | ma | ya | ra | va | la | ša | sa | ha | ksa |

A final consonant is written with a simplified variant of the basic letter in the bottom of the frame. In cases where it would conflict with the vowels u or ü the vowel is written to the left.

| 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | ||

| ag/aɣ | ak/aq | aŋ | ad/at | an | ab/ap |

| 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | ||

| am | ar | al | aš | as | ah |

Sanskrit and Tibetan

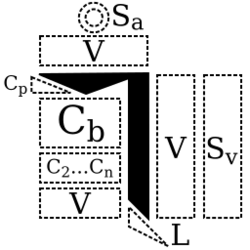

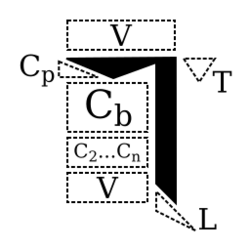

A syllable in Sanskrit or Tibetan can contain the following elements: Consonant in prefix form (Cp), consonant or vocal carrier (Cb), stack of medial consonants (C2…Cn), vowel (V) and length marker (L). For Sanskrit, there are two diacritics: anusvara (Sa) and visarga (Sv). In Tibetan, syllables can be separated by tsheg (T), a small triangle-shaped sign comparable to a space.[1]

Vowels

Sanskrit contains additional vowels ṛ, ṝ, ḷ and ḹ.

| 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | 48px | ||

| a | i | u | ṛ | ḷ | e | ai | o | au |

| 48px | 48px | 48px | ||||||

| ā | ī | ū | ṝ | ḹ |

An anusvara diacritic indicates nasalization (transcribed as ṃ).[2] A visarga indicates post-vocalic aspiration (transcribed as ḥ).[2]

| aṃ | aḥ |

Consonants

Soyombo contains the full set of letters to reproduce Sanskrit and Tibetan. Note that some of the letters represent different sounds in Mongolian, Sanskrit, and Tibetan. The primary difference between the three occurs in Mongolian where letters for Sanskrit voiceless sounds are used for voiced stops, while the letters for voiceless aspirated sounds are used for voiceless stops.[1] In Mongolian, letters used specifically for Tibetan and Sanskrit are called 'гали' galig noting they are characters used for the transcription of foreign sounds.[1]

Consonant clusters in Sanskrit and Tibetan are usually written by stacking several consonants vertically within the same frame. In existing sources clusters occur with up to three consonants, but in theory they could contain as many as possible. Four consonants, ra, la, śa and sa, can also be written as a special prefix, consisting of a small sign written to the left of the main triangle. They are pronounced before the other consonants.

Punctuation

Apart from the Soyombo symbol, the only punctuation mark is a full stop, represented by a vertical bar. In inscriptions, words are often separated by a dot at the height of the upper triangle (tsheg).

Unicode

Soyombo script has been included in the Unicode Standard since the release of Unicode version 10.0 in June 2017. The Soyombo block comprises 81 characters.[3] The proposal to encode Soyombo was submitted by Anshuman Pandey.[1] The Unicode proposal was revised in December 2015.

The Unicode block for Soyombo is U+11A50–U+11AAF:

The Menksoft IMEs provide alternative input methods.[4]

See also

- Mongolian writing systems

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Pandey, Anshuman (2015-01-26). "L2/15-004 Proposal to Encode the Soyombo Script". https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2015/15004r-soyombo.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The Unicode Standard, Chapter 14.7: Soyombo". June 2017. https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode10.0.0/ch14.pdf#G41941.

- ↑ "Unicode 10.0.0". Unicode Consortium. June 20, 2017. https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode10.0.0/. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ↑ "内蒙古蒙科立软件有限责任公司 - 首页". Menksoft.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-22. https://web.archive.org/web/20120222092700/http://www.menksoft.com/CommunityModules/ArticlesH/ArticlesViewH.aspx?pageID=0&ItemID=13546&mid=3436&wversion=Staging. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

External links

- Soyombo script - Omniglot

- Soyombo fonts (TeX/Metafont)

- Soyombo fonts (TTF)

Further reading

- Соёмбын нууц ба синергетик. Эмхэтгэсэн Б. Болдсайхан, Б. Батсанаа, Ц. Оюунцэцэг. Улаанбаатар 2005. (Secrets and Synergetic of Soyombo. Compiled by B. Boldsaikhan, B. Batsanaa, Ts. Oyuntsetseg. Ulaanbaatar 2005.)