Accidental Adversaries

Accidental Adversaries is one of the ten system archetypes used in system dynamics modelling, or systems thinking. This archetype describes the degenerative pattern that develops when two subjects cooperating for a common goal, accidentally take actions that undermine each other's success. It is similar to the escalation system archetype in terms of pattern behaviour that develops over time.[1]

Archetype description

The archetype describes a pattern where two subjects have decided to work together because they will benefit from the alliance.[2] Each take actions believing that it will bring benefit to the other and if the cooperation works, they will both benefit from it. Problems start arising when one or both of the subjects need to fix a local gap in performance, maybe due to external pressure. They initiate action to fix the gap and accidentally undermine each other's success. The result of these activities may produce a sense of resentment or frustration between the subjects or it may even turn the subjects into adversaries (hence the archetype name), thereby destroying the alliance.

History

The original set of system archetypes were published in The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge. The exact source of these generic structures is not known. However "Accidental Adversaries" has a clear origin. It is derived from observations made by Jennifer Kemeny, a colleague of Senge's and a contributor to the original archetype descriptions. In her consulting work in the late 1980s she was intrigued at how often potential strategic alliances were unsuccessful, or devolved into outright hostility. Such a recurring phenomenon suggested a structural cause. The essential elements of the archetype were first described during a session Kemeny facilitated. It was the first meeting of the first ever alliance between Walmart and Procter and Gamble. Employees diagrammed how their protective business policies caused unintentional damage to the other company – which responded with similarly defensive actions. The net effect of these "back and forth" behaviors was lower profit and less goodwill – which for a long period of time had overshadowed the possibility of mutual benefit between the organizations. An early description of "Accidental Adversaries" is in The Fifth Discipline: Fieldbook, by Senge, et al.

Description of the model

By way of example, two parties A and B have realised that by uniting forces, they can increase their success, whatever that may be. At a certain point in time, say B, takes corrective actions in order to counteract a decrease in performance due to external pressure. Although B's actions are important for B, their impact on A are not understood or not considered. The result is that now A feels that he is being betrayed and reacts to diminish the negative effects of B's actions. Ironically, A's new actions now obstruct B's success. If this situation persists and the results worsen, the alliance breaks down. A vicious circle is created and each partner has now even forgotten the original purpose of the alliance. A and B's actions now only focus on counteracting the hostile actions taken by the other. A and B thus 'accidentally' become adversaries.[3]

Causal Loop diagram

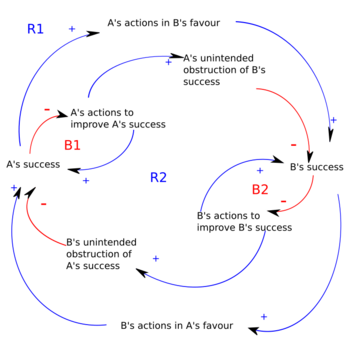

The causal loop diagram in Figure 1 shows the pattern dynamics of the system.[4]

The pattern of behaviour begins with the outer reinforcing loop R1 where A and B have formed a synergistic alliance that benefits both. An action taken by A in favour of B increases B's success and vice versa. At some point in time, though, say B, initiates a series of corrective actions in order to adjust its performance. The actions taken increase performance, whose effects balance the number of corrective actions required. This results in the creation of a balancing loop, B2. These actions also unintentionally obstruct the other party's success, and result in the formation of the negative reinforcing loop R2 that undermines the virtuous reinforcing loop R1. Now each corrective action taken by B causes A to start taking corrective measures as well, thus activating its own balancing loop B1. The formation of R2 is the critical point at which the dynamics of the system go out of control, resembling the Escalation archetype.

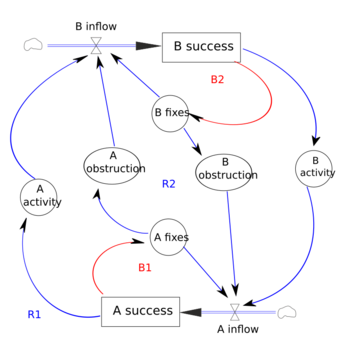

Stock and flow diagram

Figure 2 shows the stock and flow diagram for this archetype.

Alternative model

An alternative form of the model is shown in Figure 3. The differences are in the two reinforcing loops R3 and R4. Here, A and B specifically take actions to improve their growth, not, as before, to adjust their performance to a pre-determined target. By seeking improvement through R3 and R4, A and B suppress the effects of R1 and establish the negative-effect reinforcing loop R2, that in turn, completely takes over B5 and B6. The two balancing loops B5 and B6 are formed by, respectively,

- B's success->B's actions in A's favour->A's success->A's actions to improve A's success->A's unintended obstruction of B's success and

- A's success->A's actions in B's favour->B's success->B's actions to improve B's success->B's unintended obstruction of A's success.

.

Model behaviour

The archetype behaviour over time is shown in Figure 4.

Both parties show a similar trend in direction and rate of change of success, with one trailing behind the other one due to system delays. Even though the pattern shows stable periods, the overall trend follows a downward direction.[2] The above simulation can be run from InsightMaker.[5]

Possible leverage points

It is possible to achieve leverage by introducing or re-emphasising a link between each party's success,[6] thus re-establishing the outer virtuous reinforcing loop shown in Figure 3. Kemeny proposes a list of seven action steps to deal with the unintended consequences of each party's actions, given their mental models:[7]

- Reconstruct the conditions that were the catalyst for collaboration.

- Review the original understandings and expected mutual benefits.

- Identify conflicting incentives that may be driving adversarial behaviour.

- Map the unintended side effects of each party’s actions.

- Develop overarching goals that align the efforts of the parties.

- Establish metrics to monitor collaborative behaviour.

- Establish routine communication

Example

A classic example of the Accidental Adversaries system archetype is that of Procter and Gamble supplying Wal-Mart. When Procter and Gamble's profits decline, they introduce promotions. This results in extra costs and decreasing profitability for Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart's responds by stocking-up – buying large quantities of products during the discount period – and then selling them at regular prices when promotions end, thereby increasing its margins. Procter and Gamble's production now faces great swings in volume because Wal-Mart does not need to order products for months, which adds to P and G's costs. To improve their situation, Procter and Gamble pushes even more on promotions, blaming at the same time Wal-Mart for their problems. Wal-Mart reacts by stocking-up even more. Eventually, Procter and Gamble finds itself putting a lot of effort into promotions, at the expense of new product development, while Wal-Mart concentrates solely on buying and storing promoted products rather than improving their operations. The situation is described by the causal loop diagram in Figure 5. In the Procter and Gamble/Wal-Mart case, leverage was achieved by bringing both parties together to understand the structure they had unintentionally created, even though each party 's action was completely rational and understandable from their local perspective.[7]

References

- ↑ Senge, P. et al. (1994). The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook. New York: Doubleday Currency.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Braun B. (2002) The System Archetypes

- ↑ Accidental Adversaries Systems Archetype at SystemsWiki.org. "Accidental Adversaries Systems Archetype - SystemsWiki". Archived from the original on 2011-09-20. https://web.archive.org/web/20110920154719/http://www.systemswiki.org/index.php?title=Accidental_Adversaries_Systems_Archetype. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ↑ Accidental Adversaries at Systems-Thinking.org. http://www.systems-thinking.org/theWay/saa/aa.htm

- ↑ "Clone of Accidental Adversaries". http://insightmaker.com/insight/678.

- ↑ Wolstenholme E. F. (2003) Towards the definition and use of a core set of archetypal structures in system dynamics

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Kemeny J (1994) "Accidental Adversaries": When Friends Become Foes, The Systems Thinker, Vol. 5, No. 1

Further reading

Senge, Peter (1990). The Fifth Discipline. Currency. ISBN:0-385-26095-4.

Senge, P. et al. (1994). The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook. New York: Doubleday Currency.

Forrester, J. W. (1971, 1973). World Dynamics. Cambridge, MA: Wright Allen Press.

Forrester, Jay W. (1969). Urban Dynamics. Pegasus Communications. ISBN:1-883823-39-0.

Forrester, J. W. (1975). Collected Papers of Jay W. Forrester. Cambridge, MA: Wright-Allen Press.

Kim D, Kim C, A Pocket Guide to Using the Archetypes, Pegasus Communications, May 1994.

Ramsey P, Wells R, Managing the Archetypes: Accidental Adversaries, Pegasus Communications, 2001.

Kim D, Anderson V, Systems Archetype Basics: From Story to Structure, Pegasus Communications, 1998.

External links

- Systems Thinking.org

- System Dynamics Society

- SystemsWiki

- InsightMaker

- Simgua modelling tool

- Vensim modelling software

|