Inheritance (object-oriented programming)

In object-oriented programming, inheritance is the mechanism of basing an object or class upon another object (prototype-based inheritance) or class (class-based inheritance), retaining similar implementation. Also defined as deriving new classes (sub classes) from existing ones such as super class or base class and then forming them into a hierarchy of classes. In most class-based object-oriented languages like C++, an object created through inheritance, a "child object", acquires all the properties and behaviors of the "parent object", with the exception of: constructors, destructors, overloaded operators and friend functions of the base class. Inheritance allows programmers to create classes that are built upon existing classes,[1] to specify a new implementation while maintaining the same behaviors (realizing an interface), to reuse code and to independently extend original software via public classes and interfaces. The relationships of objects or classes through inheritance give rise to a directed acyclic graph.

An inherited class is called a subclass of its parent class or super class. The term "inheritance" is loosely used for both class-based and prototype-based programming, but in narrow use the term is reserved for class-based programming (one class inherits from another), with the corresponding technique in prototype-based programming being instead called delegation (one object delegates to another). Class-modifying inheritance patterns can be pre-defined according to simple network interface parameters such that inter-language compatibility is preserved.[2][3]

Inheritance should not be confused with subtyping.[4][5] In some languages inheritance and subtyping agree,[lower-alpha 1] whereas in others they differ; in general, subtyping establishes an is-a relationship, whereas inheritance only reuses implementation and establishes a syntactic relationship, not necessarily a semantic relationship (inheritance does not ensure behavioral subtyping). To distinguish these concepts, subtyping is sometimes referred to as interface inheritance (without acknowledging that the specialization of type variables also induces a subtyping relation), whereas inheritance as defined here is known as implementation inheritance or code inheritance.[6] Still, inheritance is a commonly used mechanism for establishing subtype relationships.[7]

Inheritance is contrasted with object composition, where one object contains another object (or objects of one class contain objects of another class); see composition over inheritance. Composition implements a has-a relationship, in contrast to the is-a relationship of subtyping.

History

In 1966, Tony Hoare presented some remarks on records, and in particular presented the idea of record subclasses, record types with common properties but discriminated by a variant tag and having fields private to the variant.[8] Influenced by this, in 1967 Ole-Johan Dahl and Kristen Nygaard presented a design that allowed specifying objects that belonged to different classes but had common properties. The common properties were collected in a superclass, and each superclass could itself potentially have a superclass. The values of a subclass were thus compound objects, consisting of some number of prefix parts belonging to various superclasses, plus a main part belonging to the subclass. These parts were all concatenated together.[9] The attributes of a compound object would be accessible by dot notation. This idea was first adopted in the Simula 67 programming language.[10] The idea then spread to Smalltalk, C++, Java, Python, and many other languages.

Types

There are various types of inheritance, based on paradigm and specific language.[11]

- Single inheritance

- where subclasses inherit the features of one superclass. A class acquires the properties of another class.

- Multiple inheritance

- where one class can have more than one superclass and inherit features from all parent classes.

"Multiple inheritance ... was widely supposed to be very difficult to implement efficiently. For example, in a summary of C++ in his book on Objective C, Brad Cox actually claimed that adding multiple inheritance to C++ was impossible. Thus, multiple inheritance seemed more of a challenge. Since I had considered multiple inheritance as early as 1982 and found a simple and efficient implementation technique in 1984, I couldn't resist the challenge. I suspect this to be the only case in which fashion affected the sequence of events."[12]

- Multilevel inheritance

- where a subclass is inherited from another subclass. It is not uncommon that a class is derived from another derived class as shown in the figure "Multilevel inheritance".

Multilevel inheritance - The class A serves as a base class for the derived class B, which in turn serves as a base class for the derived class C. The class B is known as intermediate base class because it provides a link for the inheritance between A and C. The chain ABC is known as inheritance path.

- A derived class with multilevel inheritance is declared as follows:

// C++ language implementation class A { ... }; // Base class class B : public A { ... }; // B derived from A class C : public B { ... }; // C derived from B

- This process can be extended to any number of levels.

- Hierarchical inheritance

- This is where one class serves as a superclass (base class) for more than one sub class. For example, a parent class, A, can have two subclasses B and C. Both B and C's parent class is A, but B and C are two separate subclasses.

- Hybrid inheritance

- Hybrid inheritance is when a mix of two or more of the above types of inheritance occurs. An example of this is when a class A has a subclass B which has two subclasses, C and D. This is a mixture of both multilevel inheritance and hierarchal inheritance.

Subclasses and superclasses

Subclasses, derived classes, heir classes, or child classes are modular derivative classes that inherit one or more language entities from one or more other classes (called superclass, base classes, or parent classes). The semantics of class inheritance vary from language to language, but commonly the subclass automatically inherits the instance variables and member functions of its superclasses.

The general form of defining a derived class is:[13]

class SubClass: visibility SuperClass

{

// subclass members

};

- The colon indicates that the subclass inherits from the superclass. The visibility is optional and, if present, may be either private or public. The default visibility is private. Visibility specifies whether the features of the base class are privately derived or publicly derived.

Some languages also support the inheritance of other constructs. For example, in Eiffel, contracts that define the specification of a class are also inherited by heirs. The superclass establishes a common interface and foundational functionality, which specialized subclasses can inherit, modify, and supplement. The software inherited by a subclass is considered reused in the subclass. A reference to an instance of a class may actually be referring to one of its subclasses. The actual class of the object being referenced is impossible to predict at compile-time. A uniform interface is used to invoke the member functions of objects of a number of different classes. Subclasses may replace superclass functions with entirely new functions that must share the same method signature.

Non-subclassable classes

In some languages a class may be declared as non-subclassable by adding certain class modifiers to the class declaration. Examples include the final keyword in Java and C++11 onwards or the sealed keyword in C#. Such modifiers are added to the class declaration before the class keyword and the class identifier declaration. Such non-subclassable classes restrict reusability, particularly when developers only have access to precompiled binaries and not source code.

A non-subclassable class has no subclasses, so it can be easily deduced at compile time that references or pointers to objects of that class are actually referencing instances of that class and not instances of subclasses (they do not exist) or instances of superclasses (upcasting a reference type violates the type system). Because the exact type of the object being referenced is known before execution, early binding (also called static dispatch) can be used instead of late binding (also called dynamic dispatch), which requires one or more virtual method table lookups depending on whether multiple inheritance or only single inheritance are supported in the programming language that is being used.

Non-overridable methods

Just as classes may be non-subclassable, method declarations may contain method modifiers that prevent the method from being overridden (i.e. replaced with a new function with the same name and type signature in a subclass). A private method is un-overridable simply because it is not accessible by classes other than the class it is a member function of (this is not true for C++, though). A final method in Java, a sealed method in C# or a frozen feature in Eiffel cannot be overridden.

Virtual methods

If a superclass method is a virtual method, then invocations of the superclass method will be dynamically dispatched. Some languages require that method be specifically declared as virtual (e.g. C++), and in others, all methods are virtual (e.g. Java). An invocation of a non-virtual method will always be statically dispatched (i.e. the address of the function call is determined at compile-time). Static dispatch is faster than dynamic dispatch and allows optimizations such as inline expansion.

Visibility of inherited members

The following table shows which variables and functions get inherited dependent on the visibility given when deriving the class, using the terminology established by C++.[14]

| Base class visibility | Derived class visibility | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Private derivation | Protected derivation | Public derivation | |

|

|

|

|

Applications

Inheritance is used to co-relate two or more classes to each other.

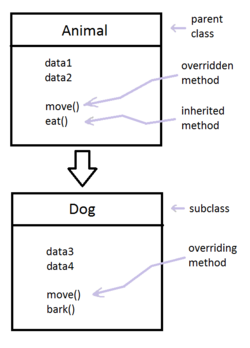

Overriding

Many object-oriented programming languages permit a class or object to replace the implementation of an aspect—typically a behavior—that it has inherited. This process is called overriding. Overriding introduces a complication: which version of the behavior does an instance of the inherited class use—the one that is part of its own class, or the one from the parent (base) class? The answer varies between programming languages, and some languages provide the ability to indicate that a particular behavior is not to be overridden and should behave as defined by the base class. For instance, in C#, the base method or property can only be overridden in a subclass if it is marked with the virtual, abstract, or override modifier, while in programming languages such as Java, different methods can be called to override other methods.[15] An alternative to overriding is hiding the inherited code.

Code reuse

Implementation inheritance is the mechanism whereby a subclass re-uses code in a base class. By default the subclass retains all of the operations of the base class, but the subclass may override some or all operations, replacing the base-class implementation with its own.

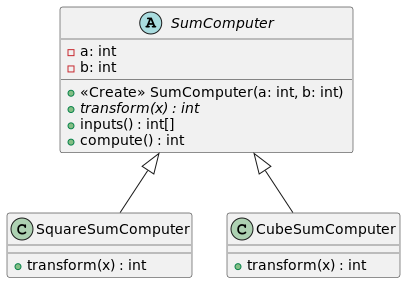

In the following Python example, subclasses SquareSumComputer and CubeSumComputer override the transform() method of the base class SumComputer. The base class comprises operations to compute the sum of the squares between two integers. The subclass re-uses all of the functionality of the base class with the exception of the operation that transforms a number into its square, replacing it with an operation that transforms a number into its square and cube respectively. The subclasses therefore compute the sum of the squares/cubes between two integers.

Below is an example of Python.

class SumComputer:

def __init__(self, a, b):

self.a = a

self.b = b

def transform(self, x):

raise NotImplementedError

def inputs(self):

return range(self.a, self.b)

def compute(self):

return sum(self.transform(value) for value in self.inputs())

class SquareSumComputer(SumComputer):

def transform(self, x):

return x * x

class CubeSumComputer(SumComputer):

def transform(self, x):

return x * x * x

In most quarters, class inheritance for the sole purpose of code reuse has fallen out of favor.[citation needed] The primary concern is that implementation inheritance does not provide any assurance of polymorphic substitutability—an instance of the reusing class cannot necessarily be substituted for an instance of the inherited class. An alternative technique, explicit delegation, requires more programming effort, but avoids the substitutability issue.[citation needed] In C++ private inheritance can be used as a form of implementation inheritance without substitutability. Whereas public inheritance represents an "is-a" relationship and delegation represents a "has-a" relationship, private (and protected) inheritance can be thought of as an "is implemented in terms of" relationship.[16]

Another frequent use of inheritance is to guarantee that classes maintain a certain common interface; that is, they implement the same methods. The parent class can be a combination of implemented operations and operations that are to be implemented in the child classes. Often, there is no interface change between the supertype and subtype- the child implements the behavior described instead of its parent class.[17]

Inheritance vs subtyping

Inheritance is similar to but distinct from subtyping.[4] Subtyping enables a given type to be substituted for another type or abstraction and is said to establish an is-a relationship between the subtype and some existing abstraction, either implicitly or explicitly, depending on language support. The relationship can be expressed explicitly via inheritance in languages that support inheritance as a subtyping mechanism. For example, the following C++ code establishes an explicit inheritance relationship between classes B and A, where B is both a subclass and a subtype of A and can be used as an A wherever a B is specified (via a reference, a pointer or the object itself).

class A {

public:

void DoSomethingALike() const {}

};

class B : public A {

public:

void DoSomethingBLike() const {}

};

void UseAnA(const A& a) {

a.DoSomethingALike();

}

void SomeFunc() {

B b;

UseAnA(b); // b can be substituted for an A.

}

In programming languages that do not support inheritance as a subtyping mechanism, the relationship between a base class and a derived class is only a relationship between implementations (a mechanism for code reuse), as compared to a relationship between types. Inheritance, even in programming languages that support inheritance as a subtyping mechanism, does not necessarily entail behavioral subtyping. It is entirely possible to derive a class whose object will behave incorrectly when used in a context where the parent class is expected; see the Liskov substitution principle.[18] (Compare connotation/denotation.) In some OOP languages, the notions of code reuse and subtyping coincide because the only way to declare a subtype is to define a new class that inherits the implementation of another.

Design constraints

Using inheritance extensively in designing a program imposes certain constraints.

For example, consider a class Person that contains a person's name, date of birth, address and phone number. We can define a subclass of Person called Student that contains the person's grade point average and classes taken, and another subclass of Person called Employee that contains the person's job-title, employer, and salary.

In defining this inheritance hierarchy we have already defined certain restrictions, not all of which are desirable:

- Singleness

- Using single inheritance, a subclass can inherit from only one superclass. Continuing the example given above, a Person object can be either a Student or an Employee, but not both. Using multiple inheritance partially solves this problem, as one can then define a StudentEmployee class that inherits from both Student and Employee. However, in most implementations, it can still inherit from each superclass only once, and thus, does not support cases in which a student has two jobs or attends two institutions. The inheritance model available in Eiffel makes this possible through support for repeated inheritance.

- Static

- The inheritance hierarchy of an object is fixed at instantiation when the object's type is selected and does not change with time. For example, the inheritance graph does not allow a Student object to become an Employee object while retaining the state of its Person superclass. (This kind of behavior, however, can be achieved with the decorator pattern.) Some have criticized inheritance, contending that it locks developers into their original design standards.[19]

- Visibility

- Whenever client code has access to an object, it generally has access to all the object's superclass data. Even if the superclass has not been declared public, the client can still cast the object to its superclass type. For example, there is no way to give a function a pointer to a Student's grade point average and transcript without also giving that function access to all of the personal data stored in the student's Person superclass. Many modern languages, including C++ and Java, provide a "protected" access modifier that allows subclasses to access the data, without allowing any code outside the chain of inheritance to access it.

The composite reuse principle is an alternative to inheritance. This technique supports polymorphism and code reuse by separating behaviors from the primary class hierarchy and including specific behavior classes as required in any business domain class. This approach avoids the static nature of a class hierarchy by allowing behavior modifications at run time and allows one class to implement behaviors buffet-style, instead of being restricted to the behaviors of its ancestor classes.

Issues and alternatives

Implementation inheritance is controversial among programmers and theoreticians of object-oriented programming since at least the 1990s. Among them are the authors of Design Patterns, who advocate interface inheritance instead, and favor composition over inheritance. For example, the decorator pattern (as mentioned above) has been proposed to overcome the static nature of inheritance between classes. As a more fundamental solution to the same problem, role-oriented programming introduces a distinct relationship, played-by, combining properties of inheritance and composition into a new concept.[citation needed]

According to Allen Holub, the main problem with implementation inheritance is that it introduces unnecessary coupling in the form of the "fragile base class problem":[6] modifications to the base class implementation can cause inadvertent behavioral changes in subclasses. Using interfaces avoids this problem because no implementation is shared, only the API.[19] Another way of stating this is that "inheritance breaks encapsulation".[20] The problem surfaces clearly in open object-oriented systems such as frameworks, where client code is expected to inherit from system-supplied classes and then substituted for the system's classes in its algorithms.[6]

Reportedly, Java inventor James Gosling has spoken against implementation inheritance, stating that he would not include it if he were to redesign Java.[19] Language designs that decouple inheritance from subtyping (interface inheritance) appeared as early as 1990;[21] a modern example of this is the Go programming language.

Complex inheritance, or inheritance used within an insufficiently mature design, may lead to the yo-yo problem. When inheritance was used as a primary approach to structure programs in the late 1990s, developers tended to break code into more layers of inheritance as the system functionality grew. If a development team combined multiple layers of inheritance with the single responsibility principle, this resulted in many very thin layers of code, with many layers consisting of only 1 or 2 lines of actual code.[citation needed] Too many layers make debugging a significant challenge, as it becomes hard to determine which layer needs to be debugged.

Another issue with inheritance is that subclasses must be defined in code, which means that program users cannot add new subclasses at runtime. Other design patterns (such as Entity–component–system) allow program users to define variations of an entity at runtime.

See also

- Archetype pattern

- Circle–ellipse problem – Problem in object-oriented programming

- Defeasible reasoning – Reasoning that is rationally compelling, though not deductively valid

- Interface (computing) – Shared boundary between elements of a computing system

- Mixin

- Polymorphism (computer science) – Using one interface or symbol with regards to multiple different types

- Protocol

- Role-oriented programming – Programming paradigm based on conceptual understanding of objects

- Trait (computer programming) – Concept used in object-oriented programming

- Virtual inheritance – Technique in the C++ language

Notes

References

- ↑ Johnson, Ralph (August 26, 1991). "Designing Reusable Classes". https://www.cse.msu.edu/~cse870/Input/SS2002/MiniProject/Sources/DRC.pdf.

- ↑ Madsen, OL (1989). "Virtual classes: A powerful mechanism in object-oriented programming". Conference proceedings on Object-oriented programming systems, languages and applications - OOPSLA '89. pp. 397–406. doi:10.1145/74877.74919. ISBN 0897913337.

- ↑ Davies, Turk (2021). Advanced Methods and Deep Learning in Computer Vision. Elsevier Science. pp. 179–342.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cook, William R.; Hill, Walter; Canning, Peter S. (1990). "Inheritance is not subtyping". Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages (POPL). pp. 125–135. doi:10.1145/96709.96721. ISBN 0-89791-343-4.

- ↑ Cardelli, Luca (1993). Typeful Programming (Technical report). Digital Equipment Corporation. p. 32–33. SRC Research Report 45.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Mikhajlov, Leonid; Sekerinski, Emil (1998). "A study of the fragile base class problem". Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Object-Oriented Programming (ECOOP). 1445. Springer. pp. 355–382. doi:10.1007/BFb0054099. ISBN 978-3-540-64737-9. http://extras.springer.com/2000/978-3-540-67660-7/papers/1445/14450355.pdf. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ↑ Tempero, Ewan; Yang, Hong Yul; Noble, James (2013). "What programmers do with inheritance in Java". ECOOP 2013–Object-Oriented Programming. 7920. Springer. pp. 577–601. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-39038-8_24. ISBN 978-3-642-39038-8. https://www.cs.auckland.ac.nz/~ewan/qualitas/studies/inheritance/TemperoYangNobleECOOP2013-pre.pdf.

- ↑ Hoare, C. A. R. (1966). Record Handling (PDF) (Technical report). pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Dahl, Ole-Johan; Nygaard, Kristen (May 1967). "Class and subclass declarations". IFIP Working Conference on Simulation Languages. Oslo: Norwegian Computing Center. https://www.ub.uio.no/fag/naturvitenskap-teknologi/informatikk/faglig/dns/dokumenter/classandsubclass1967.pdf.

- ↑ Dahl, Ole-Johan (2004). "The Birth of Object Orientation: the Simula Languages". Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2635. 15–25. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-39993-3_3. ISBN 978-3-540-21366-6. https://www.mn.uio.no/ifi/english/about/ole-johan-dahl/bibliography/the-birth-of-object-orientation-the-simula-languages.pdf.

- ↑ "C++ Inheritance". https://www.cs.nmsu.edu/~rth/cs/cs177/map/inheritd.html.

- ↑ Stroustrup, Bjarne (1994). The Design and Evolution of C++. Pearson. p. 417. ISBN 9780135229477.

- ↑ Schildt, Herbert (2003). The complete reference C++. Tata McGraw Hill. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-07-053246-5. https://archive.org/details/ccompletereferen00schi_178.

- ↑ Balagurusamy, E. (2010). Object Oriented Programming With C++. Tata McGraw Hill. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-07-066907-9.

- ↑ override(C# Reference)

- ↑ "GotW #60: Exception-Safe Class Design, Part 2: Inheritance". Gotw.ca. http://www.gotw.ca/gotw/060.htm.

- ↑ Venugopal, K.R.; Buyya, Rajkumar (2013). Mastering C++. Tata McGraw Hill Education Private Limited. p. 609. ISBN 9781259029943.

- ↑ Mitchell, John (2002). "10 "Concepts in object-oriented languages"". Concepts in programming language. Cambridge University Press. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-521-78098-8. https://archive.org/details/conceptsprogramm00mitc.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Holub, Allen (1 August 2003). "Why extends is evil". http://www.javaworld.com/article/2073649/core-java/why-extends-is-evil.html.

- ↑ Seiter, Linda M.; Palsberg, Jens; Lieberherr, Karl J. (1996). "Evolution of object behavior using context relations". ACM SIGSOFT Software Engineering Notes 21 (6): 46. doi:10.1145/250707.239108. http://www.ccs.neu.edu/research/demeter/papers/context-journal/_context.html.

- ↑ America, Pierre (1991). "Designing an object-oriented programming language with behavioural subtyping". REX School/Workshop on the Foundations of Object-Oriented Languages. 489. pp. 60–90. doi:10.1007/BFb0019440. ISBN 978-3-540-53931-5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221501695.

Further reading

- Meyer, Bertrand (1997). "24. Using Inheritance Well". Object-Oriented Software Construction (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-629155-4.

- Samokhin, Vadim (2017). "Implementation Inheritance Is Evil". HackerNoon. Medium. https://medium.com/@wrong.about/inheritance-based-on-internal-structure-is-evil-7474cc8e64dc.

|