Biography:Al-Ash`ari

Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī | |

|---|---|

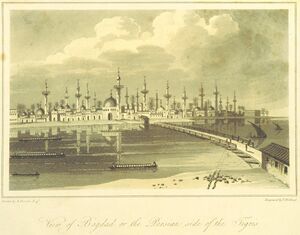

A depiction of Baghdad from 1808, taken from the print collection in Travels in Asia and Africa, etc. (ed. J. P. Berjew, British Library); al-Ashʿarī spent his entire life in this city in the twelfth-century | |

| Scholastic theologian; Champion of Islam Imām of the Scholastic Theologians Imām of the Sunnis | |

| Venerated in | Sunni Islam, but his theology has been controversial among those latter-day Sunnis who follow the Athari creed |

| Major shrine | Tomb of al-Ashʿarī, Baghdad, Iraq |

Template:Infobox Muslim scholar

Al-Ashʿarī (الأشعري; full name: Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Ismāʿīl ibn Isḥāq al-Ashʿarī; c. 874–936 (AH 260–324), reverentially Imām al-Ashʿarī) was an Arab Sunni Muslim scholastic theologian and eponymous founder of Ashʿarism or Asharite theology, which would go on to become "the most important theological school in Sunni Islam".[1]

According to scholar Jonathan A.C. Brown, although "the Ash'ari school of theology is often called the Sunni 'orthodoxy,'" "the original ahl al-hadith, early Sunni creed from which Ash'arism evolved has continued to thrive alongside it as a rival Sunni 'orthodoxy' as well."[2] According to Brown this competing orthodoxy exists in the form of the "Hanbali/über-Sunni orthodoxy"[3]

Al-Ashʿarī was notable for taking an intermediary position between the two diametrically opposed schools of theological thought prevalent at the time: He opposed both the Muʿtazilites, who advocated the extreme use of reason in theological debate, and the Zahirites, Mujassimites and Muhaddithin, who were entirely opposed to the use of reason or kalam, and condemned any theological debate altogether.[4]

Al-Ashʿari's school eventually won "wide acceptance within Sunni Islam, the official theological creed of which came largely to be defined by Ashʿarī principles."[1] Due to his efforts, Al-Ashʿarī came to be revered by Sunni Muslims for having successfully "integrated the rationalist methodology of the speculative theologians into the framework of orthodox Islam."[5] He continues to be honored by the epithets Imām al-mutakallimūn ("Leader of the Scholastic Theologians") and Imām ahl as-sunnah wa l-jamāʿah ("Leader of the Sunnis").[1]

Biography

Al-Ash'ari was born in Basra,[6] Iraq, and was a descendant of the famous companion of Muhammad, Abu Musa al-Ashari.[7] As a young man he studied under al-Jubba'i, a renowned teacher of Muʿtazilite theology and philosophy.[8] He remained a Muʿtazalite until his fortieth year when al-Ash'ari saw Muhammad in a dream 3 times in Ramadan. Muhammad told him to support what was related from himself, that is, the traditions (hadiths).[9] After this experience, he left the Muʿtazalites and became one of its most distinguished opponents, using the philosophical methods he had learned.[6] Al-Ash'ari then spent the remaining years of his life engaged in developing his views and in composing polemics and arguments against his former Muʿtazalite colleagues. He is said to have written up to three hundred works, of which only four or five are known to be extant.[10]

Views

After leaving the Muʿtazili school, and joining the side of Traditionalist theologians[11] al-Ash'ari formulated the theology of Sunni Islam.[12] He was followed in this by a large number of distinguished scholars, most of whom belonged to the Shafi'i school of law.[13] The most famous of these are Abul-Hassan Al-Bahili, Abu Bakr Al-Baqillani, al-Juwayni, Al-Razi and Al-Ghazali. Thus Al-Ash'ari’s school became, together with the Maturidi, the main schools reflecting the beliefs of the Sunnah.[13]

In line with Sunni tradition, al-Ash'ari held the view that a Muslim should not be considered an unbeliever on account of a sin even if it were an enormity such as drinking wine or theft. This opposed the position held by the Khawarij.[14]

Al-Ash'ari also believed it impermissible to violently oppose a leader even if he were openly disobedient to the commands of the sacred law.[14]

Al-Ash'ari spent much of his works opposing the views of the Muʿtazili school. In particular, he rebutted them for believing that the Qur'an was created and that deeds are done by people of their own accord.[13] He also rebutted the Muʿtazili school for denying that Allah can hear, see and has speech. Al-Ash’ari confirmed all these attributes stating that they differ from the hearing, seeing and speech of creatures, including man.[13]

He was also noted for his teachings on atomism.[15]

Legacy

The 18th century Islamic scholar Shah Waliullah stated:

- A Mujadid appears at the end of every century: The Mujadid of the first century was Imam of Ahlul Sunnah, Umar bin Abdul Aziz. The Mujadid of the second century was Imam of Ahlul Sunnah Muhammad Idrees Shaafi. The Mujadid of the third century was the Imam of Ahlul Sunnah, Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari. The Mujadid of the fourth century was Abu Abdullah Hakim Nishapuri.[16]

Earlier major scholars also held positive views of al-Ash'ari and his efforts, among them Qadi Iyad and Taj al-Din al-Subki.[17]

Works

The Ashari scholar Ibn Furak numbers Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari's works at 300, and the biographer Ibn Khallikan at 55;[18] Ibn Asāker gives the titles of 93 of them, but only a handful of these works, in the fields of heresiography and theology, have survived. The three main ones are:

- Maqālāt al-islāmīyīn,[19] it comprises not only an account of the Islamic sects but also an examination of problems in kalām, or scholastic theology, and the Names and Attributes of Allah; the greater part of this works seems to have been completed before his conversion from the Muʿtaziltes.

- Kitāb al-luma[20]

- Kitāb al-ibāna 'an usūl al-diyāna,.[21] The authenticity of this book has been called into question. For example, Richard McCarthy, in his Theology of Ash'ari, writes, "...I am unable to subscribe wholeheartedly to the proposition that the ibāna, in the form in which we have it, is a genuine work of al-Ash'ari," comparing the creed in that book to the creed found in al-Ash'ari's Maqālāt.[22]

However, George Makdisi[23] and Ignác Goldziher[24] consider this work as genuine, and Salafists maintain that the book marks al-Ash'ari's late repentance and his return to the beliefs of the salaf. Salafists expound that the book was written after he recanted his earlier beliefs and accepted Athari beliefs, following his encounter with the Hanbalite scholar Al-Hasan ibn 'Ali al-Barbahari, and was primarily an attempt to call his previous followers back to Islam.[25] Professor Sherman Jackson recounts that Ibn Taymiyyah, citing the Ash'ari Historian Ibn `Asakir, presented Al-Ashari's words in the Ibāna as a defense during his trial on charges of anthropomorphism.[26]

Early Islam scholars

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Anvari, Mohammad Javad and Koushki, Matthew Melvin, “al-Ashʿarī”, in: Encyclopaedia Islamica, Editors-in-Chief: Wilferd Madelung and, Farhad Daftary.

- ↑ Brown, Jonathan A.C. (2009). Hadith: Muhammad's Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World. Oneworld Publications (Kindle edition). p. 180.

- ↑ Brown, Jonathan (2007). The Canonization of al‐Bukhārī and Muslim: The Formation and Function of the Sunnī Ḥadīth Canon. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. Pg 137. ISBN 9789004158399.

- ↑ M. Abdul Hye,Ash’arism, Philosophia Islamica.

- ↑ Michel Adrien Allard, "Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī," Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 John L. Esposito, The Islamic World: Abbasid-Historian, p 54. ISBN:0195165209

- ↑ I.M.N. Al-Jubouri, History of Islamic Philosophy: With View of Greek Philosophy and Early History of Islam, p 182. ISBN:0755210115

- ↑ Marshall Cavendish Reference, Illustrated Dictionary of the Muslim World, p 87. ISBN:0761479295

- ↑ William Montgomery Watt, Islamic Philosophy and Theology, p 84. ISBN:0202362728

- ↑ I. M. Al-Jubouri, Islamic Thought: From Mohammed to September 11, 2001, p 177. ISBN:1453595856

- ↑ Anjum, Ovamir (2012). Politics, Law, and Community in Islamic Thought. Cambrdige University Press. p. 108. https://books.google.ca/books?id=0SePRbkpXvMC&pg=PA108&dq=ibn+hanbal+and+vindicated+by+its+triumph&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiHlKzyue7NAhVHMz4KHWOSAgUQ6AEIGzAA#v=onepage&q=ibn%20hanbal%20and%20vindicated%20by%20its%20triumph&f=false. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ John L. Esposito, The Oxford History of Islam, p 280. ISBN:0199880417

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 http://www.arabnews.com/node/211921

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Jeffry R. Halverson, Theology and Creed in Sunni Islam: The Muslim Brotherhood, Ash'arism, and Political Sunnism, p 77. ISBN:0230106587

- ↑ Ash'ari - A History of Muslim Philosophy

- ↑ Izalat al-Khafa, p. 77, part 7.

- ↑ Fatwa No. 8001. Who are the Ash'arites? - Dar al-Ifta' al-Misriyyah

- ↑ Beirut, III, p.286, tr. de Slaine, II, p.228

- ↑ ed. H. Ritter, Istanbul, 1929-30

- ↑ ed. and tr. R.C. McCarthy, Beirut, 1953

- ↑ tr. W.C. Klein, New Haven, 1940

- ↑ McCarthy, Richard J. (1953). The Theology of Al-Ashari. Imprimerie Catholique. p. 232.

- ↑ Makdisi, George. 1962. Ash’ari and the Asharites and Islamic history I. Studia Islamica 17: 37–80

- ↑ Ignaz Goldziher, Vorlesungen uber den Islam, 2nd ed. Franz Babinger (Heidelberg: C. Winter, 1925), 121;

- ↑ Richard M. Frank, Early Islamic Theology: The Mu'tazilites and al-Ash'ari, Texts and studies on the development and history of kalām, vol. 2, pg. 172. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2007. ISBN:9780860789789

- ↑ Jackson, Sherman A. “Ibn Taymiyyah on Trial in Damascus.” Journal of Semitic Studies 39 (Spring 1994): 41–85.

External links

- Imam Abu‘l-Hasan al-Ash‘ari by Shaykh Gibril Haddad

- Imam Ash’ari Repudiating Asha’rism? by Shaykh Nuh Keller

Further reading