Biography:Andrey Markov

Andrey Markov | |

|---|---|

Андрей Марков | |

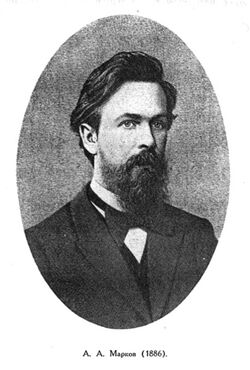

Markov in 1886 | |

| Born | 14 June 1856 Ryazan, Russia |

| Died | 20 July 1922 (aged 66) Petrograd, Russia |

| Alma mater | St. Petersburg University |

| Known for | Markov chains Markov processes Stochastic processes |

| Children | Andrey Markov Jr. |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics, specifically probability theory and statistics |

| Institutions | St. Petersburg University |

| Doctoral advisor | Pafnuty Chebyshev |

| Doctoral students |

|

Andrey Andreyevich Markov[lower-alpha 1] (14 June [O.S. 2 June] 1856 – 20 July 1922) was a Russian mathematician celebrated for his pioneering work in stochastic processes. He extended foundational results—such as the law of large numbers and the central limit theorem—to sequences of dependent random variables, laying the groundwork for what would become known as Markov chains. To illustrate his methods, he analyzed the distribution of vowels and consonants in Alexander Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, treating letters purely as abstract categories and stripping away any poetic or semantic content.

He was also a strong chess player.[citation needed]

Markov and his younger brother Vladimir Andreyevich Markov (1871–1897) proved the Markov brothers' inequality. His son, another Andrey Andreyevich Markov (1903–1979), was also a notable mathematician, making contributions to constructive mathematics and recursive function theory.[2]

Biography

Andrey Markov was born on 14 June 1856 in Ryazan, Russia. He attended the St. Petersburg Grammar School, where some teachers saw him as a rebellious student. In his academics he performed poorly in most subjects other than mathematics. Later in life he attended Saint Petersburg Imperial University. Among his teachers were Yulian Sokhotski (differential calculus, higher algebra), Konstantin Posse (analytic geometry), Yegor Zolotarev (integral calculus), Pafnuty Chebyshev (number theory and probability theory), Aleksandr Korkin (ordinary and partial differential equations), Mikhail Okatov (mechanism theory), Osip Somov (mechanics), and Nikolai Budajev (descriptive and higher geometry).

He completed his studies at the university and was later asked if he would like to stay and have a career as a mathematician. He later taught at high schools and continued his own mathematical studies. In this time he found a practical use for his mathematical skills.

In 1913, he conducted a study on the distribution of vowels and consonants in the first 20,000 letters of Alexander Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, treating the text as a sequence of symbols and analyzing the statistical relationships between them. By classifying each letter as either a vowel or a consonant and analyzing the probabilities of transitions between these categories, Markov demonstrated that chains of dependent events could be rigorously modeled. This was the first empirical application of what are now called Markov chains.

He died at age 66 on 20 July 1922.

Timeline

In 1877, Markov was awarded a gold medal for his outstanding solution of the problem:

About Integration of Differential Equations by Continued Fractions with an Application to the Equation .

During the following year, he passed the candidate's examinations, and he remained at the university to prepare for a lecturer's position.

In April 1880, Markov defended his master's thesis "On the Binary Square Forms with Positive Determinant", which was directed by Aleksandr Korkin and Yegor Zolotarev. Four years later in 1884, he defended his doctoral thesis titled "On Certain Applications of the Algebraic Continuous Fractions".

His pedagogical work began after the defense of his master's thesis in autumn 1880. As a privatdozent he lectured on differential and integral calculus. Later he lectured alternately on "introduction to analysis", probability theory (succeeding Chebyshev, who had left the university in 1882) and the calculus of differences. From 1895 through 1905 he also lectured in differential calculus.

One year after the defense of his doctoral thesis, Markov was appointed extraordinary professor (1886) and in the same year he was elected adjunct to the Academy of Sciences. In 1890, after the death of Viktor Bunyakovsky, Markov became an extraordinary member of the academy. His promotion to an ordinary professor of St. Petersburg University followed in the fall of 1894.

In 1896, Markov was elected an ordinary member of the academy as the successor of Chebyshev. In 1905, he was appointed merited professor and was granted the right to retire, which he did immediately. Until 1910, however, he continued to lecture in the calculus of differences.

In connection with student riots in 1908, professors and lecturers of St. Petersburg University were ordered to monitor their students. Markov refused to accept this decree, and he wrote an explanation in which he declined to be an "agent of the governance". Markov was removed from further teaching duties at St. Petersburg University, and hence he decided to retire from the university.

Markov was an atheist. In 1912, he responded to Leo Tolstoy's excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church by requesting his own excommunication. The Church complied with his request.[3][4]

In 1913, the council of St. Petersburg elected nine scientists honorary members of the university. Markov was among them, but his election was not affirmed by the minister of education. The affirmation only occurred four years later, after the February Revolution in 1917. Markov then resumed his teaching activities and lectured on probability theory and the calculus of differences until his death in 1922.

See also

- List of things named after Andrey Markov

- Chebyshev–Markov–Stieltjes inequalities

- Gauss–Markov theorem

- Gauss–Markov process

- Hidden Markov model

- Markov blanket

- Markov chain

- Markov decision process

- Markov's inequality

- Markov brothers' inequality

- Markov information source

- Markov network

- Markov number

- Markov property

- Markov process

- Stochastic matrix (also known as Markov matrix)

- Subjunctive possibility

Notes

References

- ↑ E.g. Shannon, Claude E. (July–October 1948). "A Mathematical Theory of Communication". Bell System Technical Journal 27 (3): 379–423. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x. Bibcode: 1948BSTJ...27..379S. http://cm.bell-labs.com/cm/ms/what/shannonday/shannon1948.pdf. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ↑ Драгалин [transliteration: "Dragalin"] (1979). (in Russian) Математический интуиционизм. Введение в теорию доказательств (English translation: "Mathematical Intuitionism: An Introduction to Proof Theory"). Наука. pp. 256.

- ↑ "Of course, Markov, an atheist and eventual excommunicate of the Church quarreled endlessly with his equally outspoken counterpart Pavel Nekrasov. The disputes between Markov and Nekrasov were not limited to mathematics and religion, they quarreled over political and philosophical issues as well." Gely P. Basharin, Amy N. Langville, Valeriy A. Naumov, The Life and Work of A. A. Markov, page 6.

- ↑ Loren R. Graham; Jean-Michel Kantor (2009). Naming Infinity: A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity. Harvard University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4. "Markov (1856–1922), on the other hand, was an atheist and a strong critic of the Orthodox Church and the tzarist government (Nekrasov exaggeratedly called him a Marxist)."

Sources

Further reading

- Karl-Georg Steffens (28 July 2007). The History of Approximation Theory: From Euler to Bernstein. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 98–105. ISBN 978-0-8176-4475-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=IjFJNoq638kC&pg=PA98.

- А. А. Марков. "Распространение закона больших чисел на величины, зависящие друг от друга". "Известия Физико-математического общества при Казанском университете", 2-я серия, том 15, с. 135–156, 1906.

- A. A. Markov. "Extension of the limit theorems of probability theory to a sum of variables connected in a chain". reprinted in Appendix B of: R. Howard. Dynamic Probabilistic Systems, volume 1: Markov Chains. John Wiley and Sons, 1971.

- Pavlyk, Oleksandr (February 4, 2013). "Centennial of Markov Chains" (in en). Wolfram Blog. http://blog.wolfram.com/2013/02/04/centennial-of-markov-chains/.

External links

|