Biography:Antoine Arnauld

Antoine Arnauld | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 February 1612 |

| Died | 8 August 1694 (aged 82)[1] Liège, Prince-Bishopric of Liège, Holy Roman Empire |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | University of Paris (Collège de Calvi and Collège de Lisieux[2]) |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

Main interests | Theology, metaphysics, epistemology, theodicy |

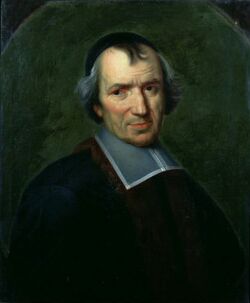

Antoine Arnauld (fr; 6 February 1612 – 8 August 1694) was a French Catholic theologian, priest, philosopher and mathematician. He was one of the leading intellectuals of the Jansenist group of Port-Royal and had a very thorough knowledge of patristics. Contemporaries called him le Grand to distinguish him from his father.

Biography

Antoine Arnauld was born in Paris to the Arnauld family. The twentieth and youngest child of the original Antoine Arnauld, he was originally intended for the bar, but decided instead to study theology at the Sorbonne. Here he was brilliantly successful, and his career was flourishing when he came under the influence of Jean du Vergier de Hauranne, the spiritual director and leader of the convent of Port-Royal, and was drawn in the direction of Jansenism.[3]

His book, De la fréquente Communion (1643), was an important step in making the aims and ideals of this movement intelligible to the general public. It attracted controversy by being against frequent communion. Furthermore, in the frame of the controversy around Jansenius' Augustinus, during which the Jesuits attacked the Jansenists claiming they were heretics similar to Calvinists, Arnauld wrote in defense the Théologie morale des Jésuites (Moral Theology of Jesuits), which would put the base of most of the arguments later used by Pascal in his Provincial Letters denouncing the "relaxed moral" of Jesuit casuistry.[4] Pascal was assisted in this task by Arnauld's nephew Antoine Le Maistre.[5] The Jesuit Nicolas Caussin, former penitentiary to Louis XIII, was charged by his order of writing a defense against Arnauld's book, titled Réponse au libelle intitulé La Théologie morale des Jésuites (1644). Other libels published against Arnauld's Moral Theology of Jesuits included the one written by the Jesuit polemist François Pinthereau (1605–1664), under the pseudonym of the abbé de Boisic, titled Les Impostures et les ignorances du libelle intitulé: La Théologie Morale des Jésuites (1644), who was also the author of a critical history of Jansenism titled La Naissance du Jansénisme découverte à Monsieur le Chancelier (The Birth of Jansenism Revealed to Sir the Chancellor, Leuven, 1654).[3]

During the formulary controversy which opposed Jesuits to Jansenists concerning the orthodoxy of Jansenius' propositions, Arnauld was forced to go into hiding. In 1655 two very outspoken Lettres à un duc et pair on Jesuit methods in the confessional brought a motion of censorship voted against him in the Sorbonne, in quite an irregular manner. This motion prompted Pascal to anonymously write the Provincial Letters. For more than twenty years Arnauld dared not appear publicly in Paris, hiding in religious retreat.[3]

Pascal, however, failed to save his friend, and in February 1656 Arnauld was ceremonially degraded. Twelve years later the so-called "peace" of Pope Clement IX put an end to his troubles; he was graciously received by Louis XIV, and treated almost as a popular hero.[3]

He now set to work with Pierre Nicole on a great work against the Calvinist Protestants: La perpétuité de la foi de l'Église catholique touchant l'eucharistie. Ten years later, however, persecution resumed. Arnauld was compelled to leave France for the Netherlands, finally settling down at Brussels. Here the last sixteen years of his life were spent in incessant controversy with Jesuits, Calvinists and heretics of all kinds. Arnauld gradually evolved away from the rigorous Augustinianism professed by Port-Royal and closer to Thomism, which also postulated the centrality of the "efficacious grace," under the influence of Nicole.[3]

His inexhaustible energy is best expressed by his famous reply to Nicole, who complained of feeling tired. "Tired!" echoed Arnauld, "when you have all eternity to rest in?" His energy was not exhausted by purely theological questions. He was one of the first to adopt the philosophy of René Descartes, though with certain orthodox reservations relating to Meditations on First Philosophy; and between 1683 and 1685 he had a long battle with Nicolas Malebranche on the relation of theology to metaphysics. On the whole, public opinion leant to Arnauld's side. When Malebranche complained that his adversary had misunderstood him, Boileau silenced him with the question: "My dear sir, whom do you expect to understand you, if M. Arnauld does not?" {{Citation needed|date=November 2007} nsive correspondence with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, regarding the latter's views detailed in his "Discourse on Metaphysics" (1686). Arnauld died, aged 82, in Brussels.[3]

Popular record for Arnauld's penetration was much increased in his L'Art de penser, commonly known as the Port-Royal Logic,[3] which kept its place as an elementary text-book until the 20th century and is considered a paradigmatical work of term logic.

Arnauld came to be regarded as important among the mathematicians of his time; one critic described him as the Euclid of the 17th century. After his death, his reputation began to wane. Contemporaries admired him as a master of intricate reasoning; on this, Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, the greatest theologian of the age, agreed with Henri François d'Aguesseau, the greatest lawyer. However, his eagerness to win every argument endeared him to no one. "In spite of myself," Arnauld once said regretfully, "my books are seldom very short." . Despite Arnauld's achievements in various fields, his name is mostly known because of Pascal's acclaimed writings, which were more fit for the general public than Arnauld's technical essays. Boileau wrote for him a famous epitaph, consecrating his memory as

“Au pied de cet autel de structure grossière

Gît sans pompe, enfermé dans une vile bière,

Le plus savant mortel qui jamais ait écrit;”

...

(“At the foot of this rough structure altar

Lies without pomp, locked in a vile casket,

The most learned mortal who ever wrote;”)

…

Antoine Arnauld's complete works (thirty-seven volumes in forty-two parts) were published in Paris, 1775–1781. There is a study of his philosophy in Francisque Bouillier, Histoire de la philosophie cartésienne (Paris, 1868); and his mathematical achievements are discussed by Franz Bopp in the 14th volume of the Abhandlung zur Geschichte der mathematischen Wissenschaften (Leipzig, 1902).

Principal works

The links are to the Gallica version.

- Œuvres complètes, Lausanne, 42 vol in-4°, 1775-1781. List of volumes online, on wikisource

- De la fréquente communion où les sentimens des Pères, des papes et des Conciles touchant l'usage des sacremens de pénitence et d'Eucharistie sont fidèlement exposez. Paris : A. Vitré, 1643. Full text in original French : [1]

- Grammaire générale et raisonnée contenant les fondemens de l'art de parler, expliqués d'une manière claire et naturelle. Paris : Prault fils l'aîné, 1754. Full text in original French : [2]

- La logique ou l'art de penser contenant outre les règles communes, plusieurs observations nouvelles, propres à former le jugement. Paris : G. Desprez, 1683. Full text in original French : [3]

- La perpétuité de la Foy de l'Eglise catholique touchant l'Eucharist deffendue contre le livre du sieur Claude. Paris: Charles Savreux, 1669.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The new Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. 1. Baker, 1960

- ↑ Walter Farquhar Hook, An ecclesiastical biography, containing the lives of ancient fathers and modern divines, interspersed with notices of heretics and schismatics, Volume 1, 1844 p. 284.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Vincent Carraud (author of Pascal et la philosophie, PUF, 1992), Le jansénisme , Société des Amis de Port-Royal, on-line since June 2007 (in French)

- ↑ Arnauld Family at concise.britannica.com, accessed 25 June 2008

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Arnauld s.v. Antoine—le grand Arnauld". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 626-627.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Arnauld s.v. Antoine—le grand Arnauld". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 626-627.

Further reading

- Nathan, Henry (1970). "Arnauld, Antoine". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 291–292. ISBN 0-684-10114-9.

External links

- Error in Template:Internet Archive author: Antoine Arnauld doesn't exist.

- Kremer, Elmer. "Antoine Arnauld". in Zalta, Edward N.. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/arnauld/.

- "Antoine Arnauld". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Antoine Arnauld", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Arnauld.html.

- The Leibniz-Arnauld correspondence, slightly modified for easier reading

"Arnauld". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913. - Has a significant section on Antoine

"Arnauld". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913. - Has a significant section on Antoine

|