Biography:Friedrich Spee

Friedrich Spee (also Friedrich Spee von Langenfeld; February 25, 1591 – August 7, 1635) was a German Jesuit priest, professor, and poet, most well known as a forceful opponent of witch trials and one who was an insider writing from the epicenter of the European witch-phobia. Spee argued strongly against the use of torture, and as an eyewitness he gathered a book full of details regarding its cruelty and unreliability.[1] He wrote, "Torture has the power to create witches where none exist."[2]

Life

Spee was born at Kaiserswerth on the Rhine. On finishing his early education at Cologne, he entered the Society of Jesus in 1610, and pursued extensive studies and activity as a teacher[1] at Trier, Fulda, Würzburg, Speyer, Worms and Mainz, where he was ordained a Catholic priest in 1622. He became professor at the University of Paderborn in 1624. From 1626 he taught at Speyer, Wesel, Trier and Cologne, and preached at Paderborn, Cologne and Hildesheim.

An attempt to assassinate Spee was made at Peine in 1629. He resumed his activity as professor and priest at Paderborn and later at Cologne, and in 1633 removed to Trier. During the storming of the city by the imperial forces in March 1635 (in the Thirty Years' War), he distinguished himself in the care of the suffering, and died soon afterwards of a plague infection contracted while ministering to wounded soldiers in a hospital.[1][3] His name is often incorrectly cited as "Friedrich von Spee".[4]

Publications

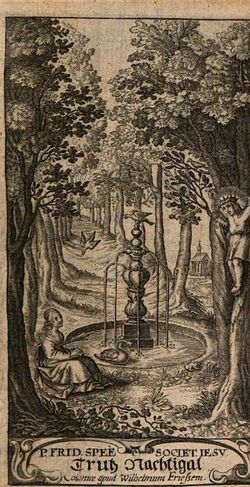

Spee's literary activity was largely confined to the last years of his life, the details of which are relatively obscure. Two of his works were not published until after his death: Goldenes Tugendbuch (Golden Book of Virtues), a book of devotion highly prized by Leibniz, and Trutznachtigall (Rivaling the Nightingale), a collection of fifty to sixty sacred songs, which take a prominent place among religious lyrics of the 17th century and have been repeatedly printed and updated through the present.

Cautio Criminalis

His principal work Cautio Criminalis is a passionate plea on behalf of those accused of witchcraft. The book was first printed anonymously in 1631 at Rinteln and attributed to an "unknown Roman theologian [Incerto Theologo Romano]."[5] It is based on his own experiences in the time and place (along the Rhine) that experienced some of the most intense and fatal witch-hunts, notably the Würzburg witch trials, during which Spee was present. Spee was present as a Jesuit confessor during sessions of torture and executions.

"If the reader will allow me to say something here, I confess that I myself have accompanied several women to their deaths in various places over the years and I am now so certain of their innocence that I feel there's no effort that would not be worth my undertaking to try to reveal this truth."[6]

Spee was reportedly brought to this awareness by a Duke of Brunswick, who invited Spee and another famous Jesuit scholar to supervise a continuation of the torture of a confessed witch. The Jesuits had previously carefully studied the issues and 'told the Duke, "The Inquisitors are doing their duty. They are arresting only people who have been implicated by the confession of other witches."' The Duke then led the Jesuits to a woman being stretched on the rack and asked her, "You are a confessed witch. I suspect these two men of being warlocks. What do you say? Another turn of the rack, executioners." “No, no!” screamed the woman. “You are quite right. I have often seen .. . They can turn themselves into goats, wolves, and other animals. ... Several witches have had children by them. ... The children had heads like toads and legs like spiders." The Duke then asked the Jesuits. "Shall I put you to the torture until you confess, my friends?" Spee thanked God he had been led to this insight by a friend, not an enemy.[7]

Spee wrote in direct opposition to many of the most well-known witch-mongers of his time and, like those works and most others in the demonological lineage going back to the 15th century, Spee also wrote in Latin.

"I pronounce from my soul that for a long time I have not known what trust I can place in those authors, Remy, Binsfeld, Delrio, and others... since virtually every one of their teachings concerning witches is based on no other foundations than fables or confessions extracted through torture."[8]

Spee pleaded for measures of reform, such as a new German imperial law on the subject, and liability to damages on the part of the judges. Cautio Criminalis contains 51 "doubts" [dubiorum] which Spee discussed and carefully de-constructed.[9] Amongst his more notable conclusions were:

- (Dubium 17) That the accused should be provided a lawyer and a legal defense, the enormity of the crime making this all the more important.

- (Dubium 20) That most prisoners will confess to anything under torture in order to stop the pain.

- (Dubium 25) Condemning the accused for not confessing under torture (i.e. having employed the so-called "sorcery of silence") is absurd.

- (Dubium 27) That torture does not produce truth, since those who wish to stop their own suffering can stop it with lies.

- (Dubium 31) Documents the barbarous cruelty, and sexual assaults on women, brought on by the practice of strip- searching and fully shaving [tonderi] every part of prisoner's body prior to the first session of torture.

- (Dubium 44) That accusations against alleged accomplices stemming from torture were of little value: either the tortured person was innocent, in which case she had no accomplices, or she was really in league with the Devil, in which case her denunciations could not be trusted either.

Spee was particularly concerned about cases where a person was tortured and forced to denounce (accuse) accomplices, who were then tortured and forced to denounce more accomplices, until everyone was under suspicion:

- "Many people who incite the Inquisition so vehemently against sorcerers in their towns and villages are not at all aware and do not notice or foresee that once they have begun to clamor for torture, every person tortured must denounce several more. The trials will continue, so eventually the denunciations will inevitably reach them and their families, since, as I warned above, no end will be found until everyone has been burned." (Dubium 15)[1]

Legacy

Cautio Criminalis helped bring an end to witch-hunting. The moral impact created by the publication was considerable. Already within the 17th century, a number of new editions and translations had appeared. Among the members of Spee's Jesuit order, his treatise found a favorable reception.

Philipp van Limborch was a Dutch Protestant but his influential History of the Inquisition (1692) refers favorably to the work of the Jesuit Spee.[10] Limborch was close with the Englishman John Locke as the two pushed for religious toleration.[11]

Hymns

Spee wrote the lyrics and tunes of dozens of hymns, and is still the most heavily attributed author in German Catholic hymnals today.[1] Although an anonymous hymnist during his lifetime, today he is credited with several popular works including the Advent song "O Heiland, reiß die Himmel auf", the Christmas carols "Vom Himmel hoch, o Engel, kommt" and "Zu Bethlehem geboren", and the Easter hymn "Lasst uns erfreuen" widely used with the 20th-century English texts "Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones" and "All Creatures of Our God and King".[citation needed]

See also

Other prominent contemporary critics of witch hunts:

- Gianfrancesco Ponzinibio (fl. 1520)

- Johannes Wier (1515–1588)

- Reginald Scot (1538–1599)

- Cornelius Loos (1546–1595)

- Anton Praetorius (1560–1613)

- Alonso Salazar y Frias (1564–1636)

- Balthasar Bekker (1634–1698)

- Robert Calef (1648–1719)

- Francis Hutchinson (1660–1739)

- Christian Thomasius (1655-1728)

- Árni Magnússon (1633–1730)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Friedrich Spee von Langenfeld: Cautio Criminalis, or a Book on Witch Trials (1631), translated by Marcus Hellyer. University of Virginia Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8139-2182-1. The translator's introduction (pp. vii–xxxvi) contains many details on Spee's life.

- ↑ "vis tormentorum parit Sagas quae non sunt" from Dubium 49 of Cautio Criminalis p. 419.

- ↑ Frank Wegerhoff, Heiko Schäfer, WDR-Fernseh-Dokumentation: Vorfahren gesucht - Wolfgang Niedecken; Rainer Decker, Neue Quellen zu Friedrich Spee von Langenfeld und seiner Familie, in: Westfälische Zeitschrift 165 (2015) S. 160f.

- ↑ Friedrich Spee zum 400 Geburtstag. Kolloquium der Friedrich-Spee-Gesellschaft Trier (in German). Paderborn: Gunther Franz, 2001.

- ↑ See 1631 Edition from Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Muenchen

- ↑ Spee, Question (Dubium) XI, Reason (Ratio) III, p. 50. For Hellyer's translation see p.39.

- ↑ Pinker (2011, pp. 138-139). Mannix (1964, pp. 134-135). McKay ( 2009, p. 320).

- ↑ Spee trans Hellyer p. 83

- ↑ "Dubiorum seu Qaeestionum huius Libri." Cautio Criminalis (1632) see Index. Note, Marcus Hellyer (2003) translates this line in the index as "doubts or questions of this book" but thereafter translates Spee's use of "Dubium" as the somewhat milder choice of "Question" i.e. "Dubium I" becomes "Question I" instead of "Doubt I." Here we are following Gerhard Schormann in leaving it in the Latin i.e. "Dubium 9" see Der Krieg gegen die Hexen (1991) p.178.

- ↑ Chapter XXI, p.231 of the Latin edition. For English translation see below.

- ↑ 1731 English translation of Limborch, see preface p.xi.

Further reading

- Cautio Criminalis, 2nd Edition, 1632[1]

- , Wikidata Q116897625

- , Wikidata Q116896896

- , Wikidata Q1520283

- Frank Sobiech: Jesuit Prison Ministry in the Witch Trials of the Holy Roman Empire. Friedrich Spee SJ and his Cautio Criminalis (1631), (Bibliotheca Instituti Historici Societatis Iesu, 80). Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, Rome 2019, ISBN 978-88-7041-380-9.

|

- ↑ Note, per Marcus Hellyer, this edition may have been anonymously shepherded into print by Spee working with a printer in Cologne (not Frankfurt). For publication history both of the Rinteln 1631 edition and of the Frankfurt (= Cologne) 1632 edition, see Frank Sobiech: Jesuit Prison Ministry in the Witch Trials of the Holy Roman Empire. Friedrich Spee SJ and his Cautio Criminalis (1631), (Bibliotheca Instituti Historici Societatis Iesu, 80). Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, Rome 2019, pp. 106-164.