Biography:Gaetano Bresci

Gaetano Bresci | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Prato, Tuscany, Italy |

| Died | 22 May 1901 (aged 31) Santo Stefano Island, Latina, Lazio, Italy |

| Occupation | Weaver |

| Movement | Anarchism in Italy |

| Conviction(s) | Murder of Umberto I |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

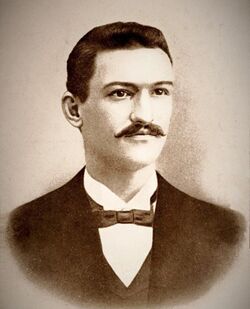

Gaetano Bresci (Italian pronunciation: [ɡaeˈtaːno ˈbreʃʃi]; 11 November 1869 – 22 May 1901) was an Italian anarchist who assassinated King Umberto I of Italy. A weaver by trade, Bresci was radicalized to anarchism at a young age, due to his experiences in poverty. He immigrated to Paterson, New Jersey, in the United States, where he became involved with other Italian immigrant anarchists. News of the Bava Beccaris massacre motivated him to return to Italy, where he planned to assassinate Umberto. Inaction from the police allowed him to return safely, while the sparse police presence during Umberto's scheduled appearance in Monza was unable to prevent Bresci from killing the king in June 1900.

The government of Italy suspected that Bresci had been a part of a conspiracy, but no evidence of such was found, indicating that Bresci had acted alone. He was consequently sentenced to life imprisonment for murder and confined on Santo Stefano Island, where he was found dead of an apparent suicide within the year. After his death, Bresci gained the status of a martyr within the Italian anarchist movement, which defended his regicidal actions. Bresci even inspired some anarchists, such as Leon Czolgosz, to carry out their own acts of propaganda of the deed. Italian anarchists erected a monument to Bresci in Carrara, despite attempts to block it by the government.

Biography

Early life

On 11 November 1869,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Gaetano Bresci was born into a lower middle-class family, in Prato, Tuscany, where he worked as a silk weaver.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) He became radicalized by his experiences in the workplace and joined the Italian anarchist movement at the age of 15.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) After being arrested and falling under police surveillance for his political dissidence, in 1895, he was exiled to Lampedusa by the government of Francesco Crispi.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In prison, Bresci studied anarchist literature and became radicalized even further by the experience.[1] Bresci was granted amnesty in 1896 and returned to the mainland, where he went back to work in a wool factory. During his time there, he developed a reputation as a dandy and engaged in numerous affairs, possibly fathering a child with one of his co-workers.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Emigration

In 1897, Bresci emigrated to the United States.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) From New York City , Bresci moved to Hoboken, New Jersey,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) where he met Sophie Kneiland, an Irish-American with whom he fathered two daughters: Madeleine and Gaetanina.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) To support his family,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Bresci spent his weekdays working as a silk weaver in Paterson,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) returning to Hoboken on weekends.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

In Paterson, Bresci quickly became involved in the local trade unions and the immigrant anarchist movement, regularly attending meetings.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) As a member of the Right to Existence Group (Italian: Gruppo diritti all' esistenza),({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Bresci co-founded the newspaper La Questione Sociale,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) which he financially supported and contributed to its publication as a prolific "firebrand".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) At one of the group's meetings, Bresci reportedly saved the life of Errico Malatesta, when he disarmed a disgruntled individualist anarchist who had shot him.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Bresci ended up leaving the Right to Existence after a few months, as he considered it to be insufficiently radical.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Assassination

After receiving news of the Bava Beccaris massacre, during which hundreds of protesting workers were killed and wounded by the Royal Italian Army, Bresci swore revenge against Umberto I of Italy, who he called the "murderer king".({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) With money from La Questione Sociale,[2] he bought a .38 caliber revolver and a one-way ticket back to Italy,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) informing his wife that he was returning in order to take care of family business.[3]

Bresci was accompanied on his journey by a number of other Italian anarchists.[4] Upon arriving in Le Havre, he and his travelling companions continued on to Paris, where they stayed for a week before finally making for Italy.[5] In June 1900, Bresci returned to his home city of Prato, where he stayed with his brother's family.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Although the local police chief was aware of his presence and knew that police records had listed him as a "dangerous anarchist", he failed to inform the interior ministry or confiscate his passport, leaving Bresci to freely practice firing his revolver on a daily basis.[6]

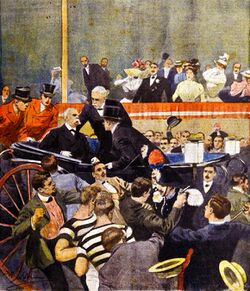

The following month, he visited his sister in Castel San Pietro Terme, before moving on to Milan.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) On 25 July, he met his friend Luigi Granotti, with whom he saw the sights of Milan before travelling to Monza.[7] Here, Bresci learnt that the King of Italy was due to attend a gymnastics competition, while staying at the local Royal Villa. Bresci found a room near the Monza train station and waited to strike.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) For two days, he scouted the area and inquired for information about the King's activities.[8]

After preparing his weapon and thoroughly grooming himself, in the morning of 29 July 1900, Bresci left his hotel intent on assassinating the King at the conclusion of the contest. He spent most of the day walking around town and eating ice cream, briefly stopping for lunch with a stranger, who he told "Look at me carefully, because you will perhaps remember me for the rest of your life."[9] That evening at 21:30, Umberto took his car to the stadium, where he was to hand out medals to the competition's athletes at 22:00. There were very few Carabinieri stationed along the route and not enough to effectively carry out crowd control at the stadium.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Bresci had positioned himself along the road that led out of the stadium, in order to give himself a chance at escape,[9] but the excited crowd swept him within three meters of the King's car and blocked his way out.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) In amongst the crowd, Bresci drew his revolver and shot Umberto.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) As the King lay dying, Bresci was accosted by the angered crowd, but was arrested by a marshal of the Carabinieri before he could be lynched.[10] He accepted arrest without resistance, declaring: "I did not kill Umberto. I have killed the King. I killed a principle."({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

Trial and conviction

A month after the assassination, Bresci's trial was held on 30 August 1900.[11] At his trial, Bresci was defended by Francesco Saverio Merlino,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) who argued that the idolization of kings had weakened Italy and that the criminalization of the anarchist movement had directly led to Umberto's assassination. He then proposed that the decriminalization of radical ideologies and the resumption of civil liberties would be an end to the anarchist "propaganda of the deed".[12] His character was further defended by his old foreman,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) a long-time co-worker,[13] and his own wife, who herself expressed surprise that her husband could have committed the assassination.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Examinations by Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso found no evidence of mental illness, which meant that the prosecution was unable to establish criminal insanity.[13]

The government of Italy assumed that Bresci had acted as part of a conspiracy.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Interior minister Giovanni Giolitti was convinced that the assassination had been plotted by Paterson anarchists, including Errico Malatesta, together with the exiled Neapolitan Queen Maria Sofia, who he alleged was planning to return to power in Italy.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Another popular conspiracy theory asserted that Giuseppe Ciancabilla had originally been selected as the assassin by a revolutionary committee in London, but was replaced by Bresci after he got into a conflict with Malatesta over the editorship of La Questione Sociale.[14] In the ensuing investigation, eleven people – including Bresci's brother, his travel companions and correspondents – were arrested and held in solitary confinement under suspicion of collaborating in the asssassination. They were finally released the following year, when the appellate court in Milan found insufficient evidence of their involvement and dropped the charges.[15] Further investigations in the United States likewise found no evidence of a conspiracy by Paterson anarchists to assassinate Umberto.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})

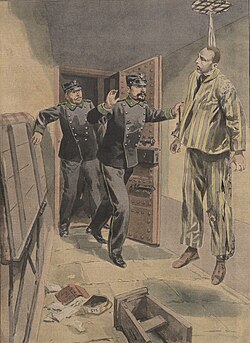

Bresci himself was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) the most severe punishment available, as Italy had already abolished the death penalty.[16] Bresci was initially held in Milan's San Vittore Prison, then transferred to a prison on Elba, where he was illegally held in an underground cell below sea level. Fears of news leaking about the conditions of his imprisonment, combined with unrest among Bresci's supporters in the prison, resulted in him being transferred again on 23 January 1901.[17] He was moved to solitary confinement on the remote Santo Stefano Island,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) where he was held in a small, unfurnished cell,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) with his feet clamped in shackles.[10]

Bresci was only allowed to keep a few personal items, such as clothing and hairstyling tools. His daily rations consisted largely of soup and bread, with meat being saved for Sundays and public holidays, and occasional wine and cheese bought with money sent by his wife.[18] For one hour of each day, he was permitted to exercise in the corridor outside his cell. The rest of his time was spent in solitary confinement, away from other prisoners and prohibited from receiving visitors, with even his own guards being forbidden from speaking to him. To keep himself entertained, he used a napkin as a makeshift football and read from a French dictionary. Bresci reportedly remained in high spirits throughout his time in prison, which the prison authorities reported was due to his belief that he would be freed from prison in an imminent revolution.[19] By May 1901, interior minister Giolitti himself began to fear that Bresci's conspirators were planning to break him out of prison.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) To deter such a plot, Giolitti deployed an armed force to guard the island.[20]

Death

On 22 May 1901,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Gaetano Bresci was found hanging by the neck in his cell.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) The word "Vengeance" had been carved into the wall.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) With his cell under constant surveillance, Bresci had apparently hanged himself while one of his guards was asleep and the other was using the toilet. The prison director reported that Bresci had hanged himself from his cell window using a towel knotted to the collar of his jacket, two items that prisoners were prohibited from possessing. All this occurred at a time that Bresci was awaiting the results of an appeal to the Court of Cassation. He also left wine and cheese, which he had reportedly purchased that very morning, uneaten.[21]

Upon receiving word of Bresci's death, interior minister Giolitti immediately dispatched a prison inspector to Santo Stefano, where he reportedly arrived late in the night of 22–23 May. The inspector and three physicians then performed an autopsy on Bresci, confirming that he had died of strangulation, but also finding that his body had undergone a level of putrefaction that suggested he had died earlier than reported. On 26 May, Bresci was buried in the prison cemetery, interred with his belongings and letters from his wife that he had not been permitted to read.[22] The New York Times celebrated the news of Bresci's death, while Umberto's successor Victor Emmanuel III commented that it was "perhaps the best thing that could have happened to the unhappy man."[11]

The circumstances of Bresci's death aroused suspicion, with a number of historians suggesting that he was murdered.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Investigations into Giolitti's papers in the Central Archives of the State found two empty folders pertaining to Bresci, in which the title of the first indicated that the prison inspector had actually arrived on the island on 18 May 1901. While looking further into the case, Italian journalist Arrigo Petacco found that Bresci's page in the Santo Stefano prison registry had been torn out.[23]

Legacy

As of Bresci's assassination of Umberto, Luigi Pelloux's reactionary government was replaced by a left-wing government under Giuseppe Saracco and Italy experienced a return to democracy. Other than a series of arrests during the investigation of the case, the state repression that Italian anarchists had expected in the wake of the assassination never actually manifested.[24]

The assassination quickly became a cornerstone of the Italian left-wing counterculture,[25] and anarchists came to regard Bresci himself as a martyr.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) On Italian anarchist postcards, Bresci's face was superimposed onto the Statue of Liberty,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) and his deeds were eulogized in a poem by Voltairine de Cleyre and in Italian revolutionary music.[26] One Roman Catholic priest was imprisoned for declaring his support for Bresci's actions, which he characterised as "an instrument of divine vengeance against a dynasty that has deprived the Popes of their temporal power."[27] In 1910, the future fascist dictator Benito Mussolini praised Bresci in the pages of the socialist newspaper Lotta di Classe.[28] Bresci's actions were also admired by Luigi Lucheni, who himself had assassinated Empress Elisabeth of Austria a few years prior.[29]

When an Italian monarchist newspaper L'Araldo Italiano raised one thousand dollars for a decoration for Umberto's tomb,[25] the Paterson anarchists responded by quickly raising the same amount to support his widow and two daughters,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) despite police harassment of their fundraising events.({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) After Bresci's regicide inspired the anarchist Leon Czolgosz to assassinate United States President William McKinley later that year,[10] Bresci's family was forced to flee their home in Cliffside Park, New Jersey, due to mounting public pressure and police surveillance.[30]

Italian anarchists from Paterson and New York established groups in his name.[31] By 1914, the New York-based Bresci group had reached 600 members, who met frequently in East Harlem's 106th Street.[32] The group was implicated in a plot to assassinate John D. Rockefeller, the richest person of the fin de siècle era. The following year, the group was infiltrated by an undercover operation and two of its members were convicted of plotting to bomb St. Patrick's Cathedral in Manhattan.[33]

In 1976, a street in Bresci's home town of Prato was named after him.[10] During the 1980s, Tuscan anarchists commissioned a monument to Bresci to be erected in Turigliano, near Carrara, but it was blocked by the government.[34][35] It was erected overnight in Turigliano cemetery (it) in 1990.[36] Vittorio Emanuele III commissioned the Expiatory Chapel of Monza to commemorate the place where his father was assassinated.[37]

See also

- List of unsolved deaths

References

- ↑ Jensen 2014, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ Kemp 2018, p. 61.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, p. 145.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, p. 146.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, p. 147.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, pp. 149.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Kemp 2018, p. 62.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Carey 1978, p. 53.

- ↑ Levy 2007, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Jensen 2014, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, pp. 151–153.

- ↑ Jensen 2014, p. 192.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, p. 164.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, p. 165.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, pp. 169–170.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, p. 166.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, p. 167.

- ↑ Pernicone & Ottanelli 2018, p. 250.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Levy 2007, p. 213.

- ↑ Kemp 2018, pp. 62–64.

- ↑ Levy 2007, pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Levy 2007, pp. 212–213.

- ↑ Jensen 2014, pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Carey 1978, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Castañeda 2017, p. 94.

- ↑ Bencivenni 2017, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Bencivenni 2017, p. 68.

- ↑ Hofmann, Paul (1991). That Fine Italian Hand. Henry Holt and Company. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-8050-1729-8. https://archive.org/details/thatfineitalianh00hofm.

- ↑ "Lost their marbles" (in en). The Economist: p. 38. 30 August 1986. ISSN 0013-0613. http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/82YwQ3.

- ↑ "'A Gaetano Bresci, Gli Anarchici' in Piazza La Statua Contestata". La Repubblica. 4 May 1990. http://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/1990/05/04/gaetano-bresci-gli-anarchici-in-piazza.html.

- ↑ Macadam, Alta (1997) (in en). Northern Italy: From the Alps to Bologna (10th ed.). London: A & C Black. p. 74. ISBN 0-7136-4294-7. https://archive.org/details/northernitalyfro0000maca/.

Bibliography

- Bencivenni, Marcella (2017). "Fired by the Ideal: Italian Anarchists in New York City, 1880s–1920s". in Goyens, Tom. Radical Gotham: Anarchism in New York City from Schwab's Saloon to Occupy Wall Street. University of Illinois Press. pp. 54–76. ISBN 978-0-252-09959-5. https://archive.org/details/radicalgothamana0000unse/.

- Carey, George W. (December 1978). "The Vessel, The Deed, and the Idea: Anarchists in Paterson, 1895-1908". Antipode 10-11 (3–1): 46–58. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.1978.tb00115.x. ISSN 1467-8330. Bibcode: 1978Antip..10...46C.

- Castañeda, Christopher J. (2017). "Times of Propaganda and Struggle: El Despertar and Brooklyn’s Spanish Anarchists, 1890–1905". in Goyens, Tom. Radical Gotham: Anarchism in New York City from Schwab's Saloon to Occupy Wall Street. University of Illinois Press. pp. 77–99. ISBN 978-0-252-09959-5. https://archive.org/details/radicalgothamana0000unse/.

- Jensen, Richard Bach (2014). "The Assassination of Umberto I of Italy". The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism: An International History, 1878–1934. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03405-1. OCLC 936070232.

- Kemp, Michael (2018). "The Cook, the Blacksmith, the King and the Weaver". Bombs, Bullets and Bread: The Politics of Anarchist Terrorism Worldwide, 1866–1926. McFarland & Company. pp. 60–64. ISBN 978-1-4766-3211-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=J7VqDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT60.

- Levy, Carl (2007). "The Anarchist Assassin and Italian History, 1870s to 1930s". Assassinations and Murder in Modern Italy. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 207–221. doi:10.1057/9780230606913_17. ISBN 978-02306-0691-3.

- Pernicone, Nunzio; Ottanelli, Fraser M (2018). Assassins Against the Old Order: Italian Anarchist Violence in Fin De Siècle Europe. University of Illinois Press. doi:10.5406/j.ctv513d7b. ISBN 978-0-252-05056-5. OCLC 1050163307.

Further reading

- Galzerano, Giuseppe (2001) (in it). Gaetano Bresci: vita, attentato, processo, carcere e morte dell'anarchico che giustiziò Umberto I. Casal Velino: Galzerano. OCLC 49712282.

- Nash, Jay Robert (1998). Terrorism in the 20th Century: A Narrative Encyclopedia From the Anarchists, through the Weathermen, to the Unabomber. M. Evans. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4617-4769-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=Rt4vCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA3.

- Pasi, Paolo (2014) (in it). Ho ucciso un princìpio. Vita e morte di Gaetano Bresci, l'anarchico che sparò al re. Milan: Elèuthera. ISBN 978-8896904503. OCLC 884723991.

- Perrone, Charles (2004). "Bresci, Gaetano". Encyclopedia of New Jersey. Rutgers University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8135-3325-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=_r9Ni6_u0JEC&pg=PA97.

- Petacco, Arrigo (2001) (in it). L'anarchico che venne dall'America. Storia di Gaetano Bresci e del complotto per uccidere Umberto I. Milan: Oscar Mondadori. ISBN 88-04-49087-X.

- Santin, Fabio; Riccomini, Marco (2006) (in it). Gaetano Bresci: un tessitore anarchico. Montespertoli: MIR Edizioni. ISBN 88-88282-88-2.

- Vecoli, Rudolph J. (1999). "Bresci, Gaetano (1869–1901), silk weaver and regicide" (in en). American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1501197. ISBN 0-19-520635-5.