Biography:Gopal Krishna Gokhale

Gopal Krishna Gokhale CIE | |

|---|---|

गोपाळ कृष्ण गोखले | |

| |

| Born | Kotluk, Dist. Ratnagiri, Bombay Presidency, British India |

| Died | 15 February 1915 (aged 48) Bombay, Bombay Presidency, British India |

| Alma mater | Elphinstone College |

| Occupation | Professor, Politician |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Movement | Indian Independence movement |

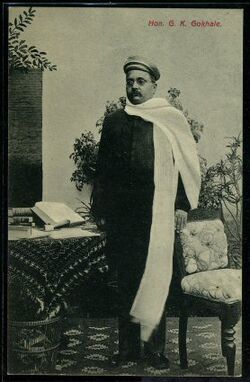

Gopal Krishna Gokhale CIE ![]() pronunciation (help·info) (9 May 1866 – 19 February 1915)[1][2][3][4] was one of the political leaders and a social reformer during the Indian Independence Movement against the British Empire in India. Gokhale was a senior leader of the Indian National Congress and founder of the Servants of India Society. Through the Society as well as the Congress and other legislative bodies he served in, Gokhale campaigned for Indian self-rule and also social reform. He was the leader of the moderate faction of the Congress party that advocated reforms by working with existing government institutions.

pronunciation (help·info) (9 May 1866 – 19 February 1915)[1][2][3][4] was one of the political leaders and a social reformer during the Indian Independence Movement against the British Empire in India. Gokhale was a senior leader of the Indian National Congress and founder of the Servants of India Society. Through the Society as well as the Congress and other legislative bodies he served in, Gokhale campaigned for Indian self-rule and also social reform. He was the leader of the moderate faction of the Congress party that advocated reforms by working with existing government institutions.

Early life

Gopal Krishna Gokhale was born on 9 May 1866 in Kotluk village of Guhagar taluka in Ratnagiri district, in present-day Maharashtra (then part of the Bombay Presidency) in a Chitpavan Brahmin Family. Despite being relatively poor, his family members ensured that Gokhale received an English education, which would place Gokhale in a position to obtain employment as a clerk or minor official in the British Raj. He studied in Rajaram college in kolhapur. Being one of the first generations of Indians to receive a university education, Gokhale graduated from Elphinstone College in 1884. Gokhale's education tremendously influenced the course of his future career – in addition to learning English, he was exposed to western political thought and became a great admirer of theorists such as John Stuart Mill and Edmund Burke.[1][3][4]

Indian National Congress, Tilak and the Split at Surat

Gokhale became a member of the Indian National Congress in 1889, as a protégé of social reformer Mahadev Govind Ranade. Along with other contemporary leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Dadabhai Naoroji, Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai and Annie Besant, Gokhale fought for decades to obtain greater political representation and power over public affairs for common Indians. He was moderate in his views and attitudes, and sought to petition the British authorities by cultivating a process of dialogue and discussion which would yield greater British respect for Indian rights.[1][2][3][4] Gokhale had visited Ireland[1][3][4] and had arranged for an Irish nationalist, Alfred Webb, to serve as President of the Indian National Congress in 1894. The following year, Gokhale became the Congress's joint secretary along with Tilak. In many ways, Tilak and Gokhale's early careers paralleled – both were Chitpavan Brahmin, both attended Elphinstone College, both became mathematics professors, and both were important members of the Deccan Education Society. However, their views concerning how best to improve the lives of Indians became increasingly apparent[1][3][4].[5]

Both Gokhale and Tilak were the front-ranking political leaders in the early 20th century. Though radically different in their ideology, fired by passion to free India from the fetters of foreign rule, Gokhale was viewed as a well-meaning man of moderate disposition, while Tilak was a radical who would not resist using force for the attainment of freedom.[1][3][4] Gokhale believed that the right course for India to give self-government was to adopt constitutional means and cooperate with the British Government. On the contrary, Tilak's messages were protest, boycott and agitation[3][1][4].

The fight between the moderates and extremists came out openly at Surat in 1907, which adversely affected political developments in the country. Both sides were fighting to capture the Congress organisation due to ideological differences. Tilak wanted to put Lala Lajpat Rai in the presidential chair, but Gokhale's candidate was Rash Behari Ghosh. The tussle begun, and there was no hope for compromise. Tilak was not allowed to move an amendment to the resolution in support of the new president-elect. At this the pandal was strewn with broken chairs and shoes were flung by Arvindo Ghosh and his friends. Sticks and umbrellas were thrown on the platform. There was a physical shuffle. When people came running to attack Tilak on the dias, Gokhale went and stood next to Tilak to protect him. The session ended, and the Congress split[1][3][4]. The eyewitness account was written by the Manchester Guardian's reporter Nevison [1][3][4][6].

In January 1908, Tilak was arrested on charge of sedition and sentenced to six years imprisonment and dispatched to Mandalay. This left the whole political field open for the moderates. When Tilak was arrested, Gokhale was in England. Lord Morley, the Secretary of State for India, was opposed to Tilak's arrest. However, the Viceroy Lord Minto did not listen to him and considered Tilak's activities as sedituious and his arrest necessary for the maintenance of law and order.[1][3][4][6]

Gokhale’s one major difference with Tilak centred around one of his pet issues, the Age of Consent Bill introduced by the British Imperial Government, in 1891–92. Gokhale and his fellow liberal reformers, wishing to purge what they saw as superstitions and abuses in their native Hinduism, supported the Consent Bill to curb child marriage abuses. Though the Bill was not extreme, only raising the age of consent from ten to twelve, Tilak took issue with it; he did not object per se to the idea of moving towards the elimination of child marriage, but rather to the idea of British interference with Hindu tradition. For Tilak, such reform movements were not to be sought under imperial rule when they would be enforced by the British, but rather after independence was achieved, when Indians would enforce it on themselves. The bill however became law in the Bombay Presidency.[1][3][4][7] The two leaders also vied for the control of the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, and the founding of the Deccan Sabha by Gokhale in 1896 was the consequence of Tilak coming out ahead[1][3][4][8].

Gokhale was deeply concerned with the future of Congress after the split in Surat. He thought it necessary to unite the rival groups, and in this connection he sought the advice of Annie Besant. On his deathbed he reportedly expressed his wish to his friend Sethur to see the Congress united.[1][3][4][6] Alas! That was not to be. He died on February 19, 1915. Though Gokhale and Tilak differed in their ideologies for attaining freedom, they had great respect for each other's patriotism, intelligence, work and sacrifice. When Gokhale died, Tilak wrote an editorial in Kesari and paid a glowing tribute to Gokhale.[1][3][4]

Economist with liberal polity

Gokhale's mentor, justice M.G. Ranade started the Sarvajanik Sabha Journal. Gokhale assisted him.[1][3][4] Gokhale's deposition before the Welby Commission on the financial condition of India won him accolades. His speeches on the budget in the Central Legislative Council were unique, with thorough statistical analysis. He appealed to the reason. He played a leading role in bringing about Morley_Minto Reforms, the beginning of constitutional reforms in India.[1][3][4] The comprehensive biography of Gopal Krishna Gokhale by Govind Talwalkar[1] portrays Gokhale's work in the context of his time, giving the historical background in the 19th century.[9] Gokhale was the scholar, the social reformer, and the statesman, arguably the greatest Indian liberal.[1][3][4]

Servants of India Society

In 1905, when Gokhale was elected president of the Indian National Congress and was at the height of his political power, he founded the Servants of India Society to specifically further one of the causes dearest to his heart: the expansion of Indian education. For Gokhale, true political change in India would only be possible when a new generation of Indians became educated as to their civil and patriotic duty to their country and to each other. Believing existing educational institutions and the Indian Civil Service did not do enough to provide Indians with opportunities to gain this political education, Gokhale hoped the Servants of India Society would fill this need. In his preamble to the SIS's constitution, Gokhale wrote that "The Servants of India Society will train men prepared to devote their lives to the cause of country in a religious spirit, and will seek to promote, by all constitutional means, the national interests of the Indian people."[1][2][3][4][10] The Society took up the cause of promoting Indian education in earnest, and among its many projects organised mobile libraries, founded schools, and provided night classes for factory workers.[11] Although the Society lost much of its vigour following Gokhale’s death, it still exists to this day, though its membership is small.

Involvement with British Imperial Government

Gokhale, though an now as the leader of the Indian nationalist movement, was not primarily concerned with independence but rather with social reform; he believed such reform would be best achieved by working within existing British government institutions, a position which earned him the enmity of more aggressive nationalists such as Tilak. Undeterred by such opposition, Gokhale would work directly with the British throughout his political career to further his reform goals.

In 1899, Gokhale was elected to the Bombay Legislative Council. He was elected to the Imperial Council of the Governor-General of India on 20 December 1901,[1][3][4][12] and again on 22 May 1903 as non-officiating member representing Bombay Province.[1][3][13][4][14]

The empirical knowledge coupled with the experience of the representative institutions made Gokhale an outstanding political leader, moderate in ideology and advocacy, a model for the people's representatives.[1][3][13][4] His contribution was monumental in shaping the Indian freedom struggle into a quest for building an open society and egalitarian nation.[1][3][13][4] Gokhale's achievement must be studied in the context of predominant ideologies and social, economic and political situation at that time, particularly in reference to the famines, revenue policies, wars, partition of Bengal, Muslim League and the split in the Congress at Surat.[1][3][13][4]

Mentor to Gandhi

Gokhale was famously a mentor to Mahatma Gandhi in latter's formative years.[1][2][3][13][4] In 1912, Gokhale visited South Africa at Gandhi's invitation. As a young barrister, Gandhi returned from his struggles against the Empire in South Africa and received personal guidance from Gokhale, including a knowledge and understanding of India and the issues confronting common Indians. By 1920, Gandhi emerged as the leader of the Indian Independence Movement. In his autobiography, Gandhi calls Gokhale his mentor and guide. Gandhi also recognised Gokhale as an admirable leader and master politician, describing him as pure as crystal, gentle as a lamb, brave as a lion and chivalrous to a fault and the most perfect man in the political field.[1][13] Despite his deep respect for Gokhale, however, Gandhi would reject Gokhale's faith in western institutions as a means of achieving political reform and ultimately chose not to become a member of Gokhale's Servants of India Society.[1][3][13][4][15]

Family

Gokhale married twice. His first marriage took place in 1880 when he was in his teens to Savitribai, who suffered from an incurable ailment. He married a second time in 1887 while Savitribai was still alive. His second wife died after giving birth to two daughters in 1899. Gokhale did not marry again and his children were looked after by his relations[1][3][13][4][16][17]

Works

- English weekly newspaper, The Hitavad (The people's paper)

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 Talwalkar, Govind (2015). Gopal Krishna Gokhale : Gandhi's political guru. New Delhi: Pentagon Press. ISBN 9788182748330. OCLC 913778097. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/913778097.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Sastri, Srinivas. My Master Gokhale.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 Talwalkar, Govind (2006). Gopal Krishna Gokhale: His Life and Times. Rupa & Co,..

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 Talwalkar, Govind (2003). Nek Namdar Gokhale ( In Marathi Language). Pune, India: Prestige Prakashan.

- ↑ Jim Masselos, Indian Nationalism: An History, Bangalore, Sterling Publishers (1991), 95.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Datta, V.N. (August 6, 2006). "A Gentle Colossus". http://www.tribuneindia.com/2006/20060806/spectrum/book1.htm.

- ↑ D. Mackenzie Brown, Indian Political Thought from Ranade to Bhave, Los Angeles: University of California Press (1961), 77.

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar. From Plassey to Partition and After (2015 ed.). Orient Blackswan Private Limited. p. 248. ISBN 978-81-250-5723-9.

- ↑ Guha, Ramchandra (24 March 2018). "In Praise of Govind Talwalkar". https://www.hindustantimes.com/columns/in-praise-of-govind-talwalkar-a-great-editor-every-city-state-in-india-needs-today/story-SLgqqqw94GsKdfq0v5PgfJ.html.

- ↑ Stanley Wolpert, Tilak and Gokhale: Revolution and Reform in the Making of Modem India, Berkeley, U. California (1962), 158–160.

- ↑ Carey A. Watt, “Education for National Efficiency: Constructive Nationalism in North India, 1909–1916,” in Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 31, No. 2 (May 1997), 341–342, 355.

- ↑ Gokhale: The Indian Moderates and the British Raj, by Bal Ram Nanda, (Princeton University Press, 2015) p133

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Govind Talwalkar, Gopal Krishna Gokhale:Gandhi's Political Guru, Pentagon Press, 2015 22.

- ↑ India List and India Office List for 1905. Harrison and Sons, London. 1905. https://books.google.com/books?id=3VQTAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA2-PA213&dq=central+provinces+and+berar&cd=6#v=onepage&q=central%20provinces%20and%20berar&f=false. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ Jim Masselos, Indian Nationalism: An History, Bangalore, Sterling Publishers (1991), 157.

- ↑ HOYLAND, JOHN S. (1933). Gopal Krishna Gokhale: His life and Speeches. CALCUTTA: Y.M.C.A. PUBLISHING HOUSE 5 RUSSELL STREET. p. 29. http://oudl.osmania.ac.in/bitstream/handle/OUDL/13455/216612_Gopal_Krishna_Gokhale_His_Life_And_Speeches.pdf?sequence=2.

- ↑ SASTRI., V.S. SRINIVASA (1937). Life of Gopal Krishna Gokhale. Bangalore India: The Bangalore Press. http://dspace.gipe.ac.in/jspui/bitstream/10973/248/6/GIPE-019745-gokhale.pdf.

Further reading

- Govind Talwalkar, Gopal Krishna Gokhale: Gandhi's Political Guru, Pentagon Press, New Delhi, 2015

- Govind Talwalkar, Gopal Krishna Gokhale: his Life and Times , Rupa Publication, Delhi, 2005

- V.S. Srinivas Sastri, My Master Gokhale

- Govind Talwalkar, Nek Namdar Gokhale (In Marathi Language), Prestige Prakashan, Pune, 2003

- J. S. Hoyland, Gopal Krishna Gokhale (1933)

External links

"Gokhale, Gopal Krishna". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

"Gokhale, Gopal Krishna". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.