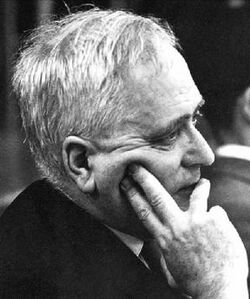

Biography:J. N. Findlay

John Niemeyer Findlay | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 November 1903 Pretoria, Transvaal Colony |

| Died | 27 September 1987 (aged 83) Boston, Massachusetts [1] |

| Nationality | South African |

| Education | Transvaal University College Balliol College, Oxford University of Graz (PhD, 1933) |

| Spouse(s) | Aileen Hawthorn |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic philosophy |

| Institutions | University of Pretoria University of Otago Rhodes University College University of Natal King's College, Newcastle King's College London University of Texas at Austin |

| Doctoral advisor | Ernst Mally |

| Notable students | Arthur Prior[2] |

Main interests | Metaphysics, ethics |

Notable ideas | Rational mysticism |

Influences

| |

John Niemeyer Findlay FBA (/ˈfɪndli/; 25 November 1903 – 27 September 1987), usually cited as J. N. Findlay, was a South African philosopher.

Education and career

Findlay read classics and philosophy as a boy and then at the Transvaal University College,[3][4] (the forerunner of the University of Pretoria).[5]

He then received a Rhodes scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford for the years 1924–1926. He completed Oxford's classics course (also known as "Greats") in June 1926, and stayed on for a fragment of a third year before returning to a lectureship appointment in South Africa. He later completed his doctorate in 1933 at Graz, where he studied under Ernst Mally. From 1927 to 1966 he was lecturer or professor of philosophy at Transvaal/University of Pretoria, the University of Otago in New Zealand, Rhodes University College, Grahamstown, the University of Natal, Pietermaritzburg, King's College, Newcastle, and King's College London. Following retirement from his chair at London (1966) and a year at the University of Texas at Austin, Findlay continued to teach full-time for more than twenty years, first as Clark Professor of Moral Philosophy and Metaphysics at Yale University (1967–1972), then as University Professor and Borden Parker Bowne Professor of Philosophy (succeeding Peter Bertocci) at Boston University (1972–1987).[6][7][8][9]

Findlay was president of the Aristotelian Society from 1955 to 1956 and president of the Metaphysical Society of America from 1974 to 1975, as well as a Fellow of both the British Academy and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[10] He was also an Editorial Advisor of the journal Dionysius. A chair for visiting professors at Boston University carries his name, as does a biennial award given for the best book in metaphysics, as judged by the Metaphysical Society of America. Findlay betrayed a great commitment to the welfare and formation[11] of generations of students (Leroy S. Rouner was fond of introducing him as "Plotinus incarnate"),[citation needed] teaching philosophy in one college classroom after another for sixty-two consecutive academic years. On 10 September 2012 Findlay was voted the 8th "most underappreciated philosopher active in the U.S. from roughly 1900 through mid-century" in a poll conducted among readers of Leiter Reports: A Philosophy Blog, finishing behind George Santayana, Alfred North Whitehead, and Clarence Irving Lewis.[12]

Findlay's autobiographical essay "Confessions of Theory and Life" is printed in Transcendence and the Sacred (1981).[13] Findlay's "My Life” is found in Studies in the Philosophy of J. N. Findlay (1985).[14]

Work

Rational mysticism

At a time when scientific materialism, positivism, linguistic analysis, and ordinary language philosophy were the core academic ideas, Findlay championed phenomenology, revived Hegelianism, and wrote works that were inspired by Theosophy,[15] Buddhism, Plotinus, and Idealism. In his books published in the 1960s, including two series of Gifford Lectures, Findlay developed rational mysticism. According to this mystical system, "the philosophical perplexities, e.g., concerning universals and particulars, mind and body, knowledge and its objects, the knowledge of other minds,".[16] as well as those of free will and determinism, causality and teleology, morality and justice, and the existence of temporal objects, are human experiences of deep antinomies and absurdities about the world. Findlay's conclusion is that these necessitate the postulation of higher spheres, or "latitudes", where objects' individuality, categorical distinctiveness and material constraints are diminishing, lesser in each latitude than in the one below it. On the highest spheres, existence is evaluative and meaningful more than anything else, and Findlay identifies it with the idea of The Absolute.[17]

Husserl and Hegel

Findlay translated into English Husserl's Logische Untersuchungen (Logical Investigations), which he regarded as the author's best work, representing a developmental stage when the idea of phenomenological bracketing was not yet taken as the basis of a philosophical system, covering in fact for loose subjectivism. To Findlay, the work was also one of the peaks of philosophy generally, suggesting superior alternatives both for overly minimalistic or naturalistic efforts in ontology and for Ordinary Language treatments of consciousness and thought.[18][19] Findlay also contributed final editing and wrote addenda to translations of Hegel's Logic and Phenomenology of Spirit.

Wittgenstein

Findlay was first a follower, and then an outspoken critic of Ludwig Wittgenstein.[20] He denounced his three theories of meaning, arguing against the idea of Use, prominent in Wittgenstein's later period and in his followers, that it is insufficient for an analysis of meaning without such notions as connotation and denotation, implication, syntax and most originally, pre-existent meanings, in the mind or the external world, that determine linguistic ones, such as Husserl has evoked. Findlay credits Wittgenstein with great formal, aesthetic and literary appeal, and of directing well-deserved attention to Semantics and its difficulties.[21]

Works

Books

- Meinong's Theory of Objects, Oxford University Press, 1933; 2nd ed. as Meinong's Theory of Objects and Values, 1963

- Hegel: A Re-examination, London: Allen & Unwin/New York: Macmillan, 1958 (Muirhead Library of Philosophy)

- Values and Intentions: A Study in Value-theory and Philosophy of Mind, London: Allen & Unwin, 1961 (Muirhead Library of Philosophy)

- Language, Mind and Value: Philosophical Essays, London: Allen & Unwin/New York: Humanities Press, 1963 (Muirhead Library of Philosophy)

- The Discipline of the Cave, London: Allen & Unwin/New York: Humanities Press, 1966 (Muirhead Library of Philosophy) (Gifford Lectures 1964–1965 [1])

- The Transcendence of the Cave, London: Allen & Unwin/New York: Humanities Press, 1967 (Muirhead Library of Philosophy) (Gifford Lectures 1965–1966 [2])

- Axiological Ethics, London: Macmillan, 1970

- Ascent to the Absolute: Metaphysical Papers and Lectures, London: Allen & Unwin/New York: Humanities Press, 1970 (Muirhead Library of Philosophy)

- Psyche and Cerebrum, Aquinas lecture. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1972

- Plato: The Written and Unwritten Doctrines, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul/New York: Humanities Press, 1974 [22]

- Plato and Platonism, New York: New York Times Book Co., 1976

- Kant and the Transcendental Object, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981

- Wittgenstein: A Critique, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984

Articles/book chapters

- "Time: A Treatment of Some Puzzles"", Australasian Journal of Psychology and Philosophy, Vol. 19, Issue 13 (December 1941): 216–235, reprinted in Language, Mind and Value

- "Morality by Convention", Mind, Vol. 33, No. 210 (1944): 142–169, reprinted in Language, Mind and Value

- "Can God's Existence Be Disproved?", Mind, Vol. 37, No. 226 (1948): 176–183; reprinted in Language, Mind and Value, and, with discussion, in Flew, A. and MacIntyre, A. C., (eds.), New Essays in Philosophical Theology, New York: Macmillan, 1955

- "Linguistic Approach to Psychophysics", Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 1949–1950, reprinted in Language, Mind and Value

- "The Justification of Attitudes", Mind, Vol. 43, No. 250 (1954): 145–161, reprinted in Language, Mind and Value

- "I.—Some Merits of Hegelianism: The Presidential Address," Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Volume 56, Issue 1, 1 June 1956, pp. 1–24

- “The Structure of the Kingdom of Ends”, Henrietta Hertz Lecture, read at the British Academy, (1957)

- "Use, Usage and Meaning", Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary Volumes, Vol. 35. (1961), pp. 223–242

- “The Systematic Unity of Value,” in Akten Des XIV. Internationalen Kongresses Für Philosophie, (1968) Reprinted in Ascent to the Absolute

- “Hegel and the Philosophy of Physics”, in J. J. O’Malley et al (eds.) The Legacy of Hegel: Proceedings of the Marquette Hegel Symposium 1970 (1973)

- "Foreword", in Frederick G. Weiss, ed., Hegel: The Essential Writings, Harper & Row/Harper Torchbooks, 1974. ISBN 0-06-131831-0

- "Foreword", in Hegel’s Logic, William Wallace (trans.), Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1975. ISBN 978-0-19-824512-4 [3]

- "Foreword", in Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit, Oxford University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-19-824597-1

- "Analysis of the Text", in Phenomenology of Spirit, Oxford University Press, 1977: 495–592. ISBN 978-0-19-824597-1 [4]

- "The Myths of Plato", Dionysius, Volume II (1978): 19–34, (reprinted in Alan Olson, ed., Myth, Symbol, and Reality', South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, 1980, 165–84)

- “The Impersonality of God” in God, the Contemporary Discussion, Frederick Sontag & M. Darrol Bryant (eds) (1982)

- "Plato's Unwritten Dialectic of the One and the Great and Small" (1983) The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter, 113.

- “The Hegelian Treatment of Biology and Life”, in Hegel and the Sciences, Robert S. Cohen and Marx W. Wartofsky (eds), (1984)

- "My Life” and "My Encounters with Wittgenstein" in Studies in the Philosophy of J. N. Findlay (1985)

- Findlay's Nachlass (list of posthumous essays derived from Findlay’s lecture notes and published in The Philosophical Forum)

Translations

- Logical Investigations (Logische Untersuchungen), by Edmund Husserl, with an introduction by J.N. Findlay, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. (1970)

Notes

- ↑ John R. Shook (ed.), Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, Thoemmes, 2005, p. 779.

- ↑ Gabbay, Dov M.; Woods, John (2006-05-10) (in en). Logic and the Modalities in the Twentieth Century. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-046303-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=gpwZYXsomEsC&pg=PA400.

- ↑ Kim, Bockja (2010), "Findlay, John Niemeyer" (in en), The Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers (Continuum), doi:10.1093/acref/9780199754663.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-975466-3, https://books.google.com/books?id=Ijpj1tB3Qr0C&pg=PA778, retrieved 2022-05-06, "In 1919, as he began undergraduate studies at Transvaal University College, he became fascinated with the Theosophical Society’s blend of Oriental religious beliefs, which developed into a serious study of Hindu, Buddhist, and Neoplatonist writings. Findlay earned a BA at Transvaal in 1922 and an MA in 1924."

- ↑ Brown, Stuart; Bredin, Hugh Terence (2005-08-01) (in en). Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British Philosophers. A&C Black. pp. 281. ISBN 978-1-84371-096-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=uL3UAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA281. "He was educated at Pretoria High School for Boys and Transvaal University College [...] on the award of a Rhodes Scholarship, from 1924 to 1926 he studied at Balliol College, Oxford, [...] At Oxford he gained a first in the school of literae humaniores. Over his career as a philosophical teacher he held various posts in different countries, beginning in 1927 as lecturer in philosophy at Transvaal University College. During this time, after two extended research visits, he was awarded a doctorate by the University of Graz in Austria for his work on Brentano."

- ↑ "Foundation Years: 1889 – 1929 | Article | University of Pretoria". https://www.up.ac.za/article/2876718/foundation-years-1889-1929.

- ↑ Howard, Alana. "Biography". Gifford Lecture Series. http://www.giffordlectures.org/Author.asp?AuthorID=63.

- ↑ Harris, Errol (Spring 1988), "In Memoriam: John Niemeyer Findlay", Owl of Minerva 19 (2): 252–253, doi:10.5840/owl198819245, https://www.pdcnet.org/owl/content/owl_1988_0019_0002_0252_0253

- ↑ "Awards – Department of Philosophy at Boston University". http://www.bu.edu/philo/awards/index.html#findlay.

- ↑ Quinton, Anthony (1997). "Findlay, John Niemeyer". Biographical dictionary of twentieth-century philosophers. Stuart C. Brown, Diané Collinson, Robert Wilkinson. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06043-5. OCLC 38862354. https://archive.org/details/biographicaldict0000unse_b8m6/page/234/mode/2up.

- ↑ "John Niemeyer Findlay" (in en). https://www.amacad.org/person/john-niemeyer-findlay. "John Niemeyer Findlay (1903 – 1987) Boston University; Boston, MA Philosopher; Educator AREA Humanities and Arts SPECIALTY Philosophy and Religious Studies ELECTED 1975"

- ↑ '"I owe to [Findlay’s] teaching, directly or indirectly, all that I know of either Logic or Ethics" (A. N. Prior).

- ↑ "Underappreciated philosophers active in the U.S. from roughly 1900 through mid-century?". https://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2012/09/underappreciate-philosophers-active-in-the-us-from-roughly-1900-through-mid-century.html.

- ↑ Transcendence and the sacred. Notre Dame, Ind. : University of Notre Dame Press. 1981. ISBN 978-0-268-01841-2. http://archive.org/details/transcendencesac0000unse.

- ↑ Cohen, R. S. (Robert Sonné); Martin, R. M. (Richard Milton); Westphal, Merold (1985). Studies in the philosophy of J.N. Findlay. Albany : State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-795-3. http://archive.org/details/studiesinphiloso00cohe.

- ↑ "[My Gifford Lectures] ... represent my attempt to cull an eternal, necessary theosophy from the defective theosophic teaching of my adolescence" (Studies in the Philosophy of J. N. Findlay, p. 45). Findlay's Gifford Lectures also may well constitute the most comprehensive defense of the doctrine of the transmigration of the soul (reincarnation) in 20th-century academic philosophy.

- ↑ Findlay, J. N. (1966), "Preface", written at London, The Transcendence of the Cave, New York: Humanities Press (published 1967), http://www.giffordlectures.org/Browse.asp?PubID=TPTCAV&Volume=0&Issue=0&ArticleID=1

- ↑ Drob, Sanford L, Findlay's Rational Mysticism: An Introduction, http://www.jnfindlay.com/findlay/about/index.html

- ↑ Findlay, J. N. (1970), "Translator's Introduction (Abridged)", written at New Haven, Connecticut, in Moran, Dermot, Logical Investigations, I, New York: Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0-415-24189-8

- ↑ Ryle, Gilbert; Findlay, J. N. (1961), "Symposium: Use, Usage and Meaning", Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary Volumes 35: 240, https://www.sfu.ca/~jeffpell/Phil467/RyleUseUsage61.pdf, retrieved 2008-06-14

- ↑ see Findlay's Wittgenstein: A Critique, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984

- ↑ Ryle, Gilbert; Findlay, J. N. (1961), "Symposium: Use, Usage and Meaning", Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary Volumes 35: 231–242, https://www.sfu.ca/~jeffpell/Phil467/RyleUseUsage61.pdf, retrieved 2008-06-14

- ↑ Findlay's findings herein are summarized in his "Plato's Unwritten Dialectic of the One and the Great and Small" (1983). The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter. 113. (available as an Open Access download).

References

- Robert S. Cohen, Richard M. Martin, and Merold Westphal (eds.), Studies in the Philosophy of J.N. Findlay, Albany NY: State University of New York Press, 1985 (Includes autobiographical note by Findlay and his account of encounters with Wittgenstein). ISBN 978-0-87395-795-3

- Bockja Kim, Morality as the End of Philosophy: The Teleological Dialectic of the Good in J.N. Findlay's Philosophy of Religion, University Press of America, 1999. ISBN 978-0-7618-1490-0

- Michele Marchetto, Impersonal Ethics: John Niemeyer Findlay's Value-theory, Avebury, 1996. ISBN 978-1-85972-272-5

- Douglas Lackey, "John Niemeyer Findlay". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

External links

- John Niemeyer Findlay 1903–1987, Alasdair MacIntyre, Hegel Bulletin, Volume 8, Issue 2 (number 16), Autumn/Winter 1987 , pp. 4–7. (Open Access).

- John Niemeyer Findlay 1903–1987, Alasdair MacIntyre, Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 111, 2001, pp. 429–512.

- John Niemeyer Findlay tribute page by Dr. Sanford L. Drob

- Philosophical History: The Otago Department

- Gifford Lecture Series – Biography – John Niemeyer Findlay