Biography:Naiche

Naiche | |

|---|---|

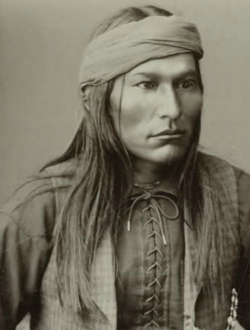

Chiricahua Chokonen N'de Chief Naiche, Arizona | |

| Born | c. 1857 Chiricahua country |

| Died | Mescalero, New Mexico |

| Allegiance | Chiricahua Apache Indians |

| Years of service | 1880–1886 |

| Rank | Chief or Leader of Chiricahua Apaches |

| Battles/wars | Apache Wars |

| Relations | Cochise (father) |

| Other work | artist |

Chief Naiche (/ˈnaɪtʃi/ NYE-chee;[1] c. 1857–1919) was the final hereditary chief of the Chiricahua band of Apache Indians.[2]

Background

Naiche, whose name in English means "meddlesome one" or "mischief maker", is alternately spelled Nache, Nachi, or Natchez.[2]

He was the youngest son of Cochise and his wife Dos-teh-seh (Dos-tes-ey, - "Something-at-the-campfire-already-cooked", b. 1838), His older brother was Tah-zay aka Chief Taza.[3]

Naiche was described as a tall, handsome man with a dignified bearing that reflected the Apache equivalent of a royal bloodline as the son of Cochise (leader of the Chihuicahui local group of the Chokonen and principal chief of the Chokonen band of the Chiricahua Apache) and Dos-teh-seh, daughter of the great Warm Spring/Mimbreño Chief Mangas Coloradas.[4] Britton Davis described him as being 6'1" in height, which was tall for an Apache.[3]

He had three wives, Haozinne, E-Clah-he, and Na-deh-yole, and fourteen children.[4]

Career

Upon the death of his father Cochise in 1874, Naiche's brother Taza became the chief; however, Taza died a few years later in 1876, and the office went to Naiche. In the 1880s, Naiche and Geronimo successfully went to war together.[3]

In 1880, Naiche traveled to Mexico with Geronimo's band, to avoid forced relocation to the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in Arizona. They surrendered in 1883 but escaped the reservation in 1885, back into Mexico.[5]

Officially the leader of the last band of renegade Apaches in the Southwest, Naiche and Geronimo surrendered to General Nelson Miles in 1886.[6]

Naiche and other Apaches requested to return to Arizona, while still imprisoned in Fort Marion. The US did not allow their return, but Kiowa and Comanche tribes offered to share their reservations in southwestern Oklahoma with the Chiricahua, so Naiche and 295 members of his band moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where they became the Fort Sill Apache Tribe. In 1913, Naiche moved to the Mescalero Indian Reservation in New Mexico.[7]

Naiche had the reputation of being the finest Indian artist of that period. He painted his pictures on deer skin in color. His subjects were flowers, deer, other wild animals, turkey, and various objects of nature, as he saw them. He also carved canes from wood and painted them in different colors.[8]

Death

Naiche died of influenza on March 16, 1919 in Mescalero, New Mexico.[2]

Among his descendants:

- Elbys Onea Naiche Hugar

- Silas Cochise

In fiction

Naiche is one of the central characters in the novel Cry of Eagles by William W. Johnstone. The story features Naiche leading a renegade band of Apache in open warfare against white settlers and miners as they attempt to join Geronimo in Mexico. In the final chapter Naiche is killed by the book's protagonist, Falcon MacCallister.[9] Naiche is played by Rex Reason in Douglas Sirk's film Taza, Son of Cochise.

Naiche identified as "Chief Nachez" was a character in Season 6 Episode 22 of The Life And Legend of Wyatt Earp. This episode aired on March 7, 1961. In the episode the Chief Nachez character turns to Wyatt Earp for help in stopping the selling of liquor to members of his tribe. The "Nachez" character was played by George Keymas.[10]

References

- ↑ "St. Joseph's Apache Mission". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_L0YsojuiOg. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Johansen, Bruce E. "Naiche (ca. 1857–1919)." Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. (retrieved 25 Sept 2011)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Delgadillo, Alicia (1 June 2013). From Fort Marion to Fort Sill: A Documentary History of the Chiricahua Apache Prisoners of War, 1886–1913. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 193–. ISBN 978-0-8032-4625-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=iIrWsLDXRqUC&pg=PA193.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Robinson, Sherry (25 April 2016). Apache Voices: Their Stories of Survival as Told to Eve Ball. University of New Mexico Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8263-1848-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=LjFIDAAAQBAJ&pg=PT77.

- ↑ Sheridan, Thomas E. (1998). A History of the Southwest: The Land and Its People. Western National Parks Association. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-877856-76-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=msXwj_0eVRYC&pg=PA41.

- ↑ Kraft, Louis (1 June 2000). Gatewood and Geronimo. University of New Mexico Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-8263-5405-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=fIW7CwAAQBAJ&pg=PT203.

- ↑ Champagne, Duane (1994). Chronology of Native North American History: From Pre-Columbian Times to the Present. Gale Research. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-8103-9195-6. https://archive.org/details/chronologyofnati00duan.

- ↑ Griffin-Pierce, Trudy (13 August 2013). The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Southwest. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-231-52010-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=LdrmWsXR7poC&pg=PA124.

- ↑ William W. Johnstone Cry of Eagles. Published October 1999, Pinnacle Books/Kennsington Publishing Corp.

- ↑ Lentz, Harris M. (1 January 1997). Television Westerns Episode Guide: All United States Series, 1949–1996. McFarland & Company. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7864-0377-6.