Biography:Tracy Hall

Tracy Hall | |

|---|---|

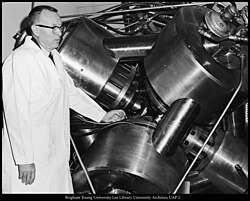

Hall in 1960 | |

| Born | Howard Tracy Hall October 20, 1919 Ogden, Utah, U.S. |

| Died | July 25, 2008 (aged 88) Provo, Utah, U.S. |

| Known for | among the pioneer researchers of synthetic diamonds |

Howard Tracy Hall (October 20, 1919 – July 25, 2008) was an American physical chemist and one of the early pioneers in the research of synthetic diamonds, using a press of his own design.

Early life

Howard Tracy Hall was born in Ogden, Utah in 1919. He often used the name H. Tracy Hall or, simply, Tracy Hall. He was a descendant of Mormon pioneers and grew up on a farm in Marriott, Utah. When still in the fourth grade, he announced his intention to work for General Electric. Hall attended Weber College for two years, and married Ida-Rose Langford in 1941. He went to the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he received his BSc in 1942 and his MSc in the following year. For the next two years, he served as an ensign in the U.S. Navy. Hall returned to the University of Utah in 1946, where he was Henry Eyring's first graduate student, and was awarded his PhD in physical chemistry in 1948. Two months later, he realized his childhood dream by starting work at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York. He joined a team focused on synthetic diamond making, codenamed "Project Superpressure" headed by engineer Anthony Nerad.[1]

GE synthetic diamond project

Hall produced synthetic diamond in a press of his own design[2] on December 16, 1954, and showed that he and others could repeat the process following Hall's procedure, a success which led to the creation of a major supermaterials industry. Hall was one of a group of about a half dozen researchers who had focused on achieving the synthesis for almost four years. These years had seen a succession of failed experiments, an increasingly impatient management, and a complex blend of sharing and rivalries among the researchers.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag Upon breaking open the sample, clusters of diamond octahedral crystals were found on the tantalum metal disks, which apparently acted as a catalyst.

GE went on to make a fortune with Hall's invention. GE rewarded Hall with a $10 savings bond.[3]

Later years

Hall left GE in 1955 and became a full professor of chemistry and director of research at Brigham Young University. At BYU, he invented the tetrahedral and cubic press systems.[4] He transferred the technology for the cubic press system to China in about 1960, and today the vast majority of the world's synthetic diamond powder is produced using the many thousands of cubic presses of Hall's design presently operating in that country. For many years, the first tetrahedral press was displayed in the Eyring Science center on campus at BYU. In the early 1960s, Hall invented the first form of polycrystalline diamond (PCD). He co-founded MegaDiamond in 1966, and later was involved with the founding of Novatek, both of Provo, Utah.

On Sunday, July 4, 1976, he became a bishop in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and served five years. Later he served a church mission to southern Africa with his wife, Ida-Rose Langford. He died on July 25, 2008, in Provo, Utah, at the age of 88. He had seven children, 35 grandchildren and 53 great-grandchildren.

Honors and awards

- 1970 Chemical Pioneer Award by the American Institute of Chemists.[5]

- 1972 American Chemical Society Award for Creative Invention: "For being the first to discover a reproducible reaction system for making synthetic diamonds from graphite, and for the concept and design of a super high pressure apparatus which not only made the synthesis possible, but brought about a whole new era of high pressure research."[1][6]

- 1977 James C. McGroddy Prize for New Materials from the American Physical Society.

- 1994 Utah Governor's Medal for Science and Technology.

- 2004 Honorary degree in Science from the University of Utah[7][8]

- 2016 Weber State University dedicated its new science building in his honor: the Tracy Hall Science Center.[9]

In popular culture

- In the "Peekaboo" episode of Breaking Bad, Walter White mentions that Hall "invented the synthetic diamond" and received only a $10 savings bond from GE for his invention while GE made a fortune, and speaks of the irony of a carbon-based life form being paid in a carbon paper certificate for his work with carbon.[10]

Patents

He was granted 19 patents in his career. Some especially notable ones were:

- U.S. Patent 2,947,608 or [1] "Diamond Synthesis" Howard Tracy Hall, Aug. 2, 1960.

- U.S. Patent 2,947,610 or [2] "Method of Making Diamonds" Howard Tracy Hall, Herbert M. Strong and Robert H. Wentorf, Jr., Aug. 2, 1960.

- U.S. Patent 3,159,876 or [3] "High Pressure Press" Howard Tracy Hall, Dec. 8, 1964.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Tracy Hall, Leading Figure in Diamond Synthesis, Dies Aged 88". element six. http://www.e6.com/en/newscentre/pressreleases/name,901,en.html. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ H. T. Hall (1960). "Ultra-high pressure apparatus". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 31 (2): 125. doi:10.1063/1.1716907. Bibcode: 1960RScI...31..125H. http://67.50.46.175/pdf/19600162.pdf.

- ↑ Maugh II, Thomas H. (2008-07-31). "General Electric chemist invented process for making diamonds in lab". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2008-jul-31-me-hall31-story.html. Retrieved 2017-03-01.

- ↑ "Machine Studies Metals' Strength" (in en-US). The New York Times. 1964-11-06. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1964/11/06/archives/machine-studies-metals-strength.html.

- ↑ "Chemical Pioneer Award". American Institute of Chemists. http://www.theaic.org/award_winners/chem_pioneer.html#cpa60s. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmakers - ↑ Hawkins, Katrina Lynn Corbridge; March 8, KSL.com Posted-; A.m, 2016 at 11:45. "Utah inventions: A better synthetic diamond" (in en). KSL. https://www.ksl.com/article/38801925/utah-inventions-a-better-synthetic-diamond.

- ↑ "Honorary Degree Recipients by Year (1892-2024) - University Leadership" (in en-US). University of Utah. https://administration.utah.edu/honorary-degree-recipients-by-year/.

- ↑ "Tracy Hall Science Center". Weber State University College of Science. https://www.weber.edu/cos/TracyHall.html. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ↑ Kelly, Jeff (2014-01-16). "The Scientist Who Got $10 For A World-Changing Invention". http://knowledgenuts.com/2014/01/16/the-scientist-who-got-10-for-a-world-changing-invention/. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

External links

|