Biology:Accessory nerve

| Accessory nerve | |

|---|---|

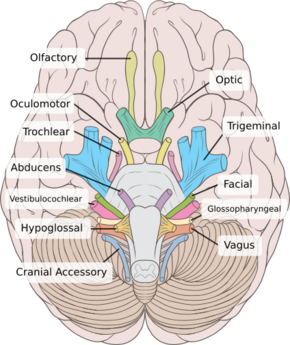

View of the human brain from below. The accessory nerve emerges from the medulla of the brainstem, and is visible at the bottom of the image in blue. | |

| Details | |

| Innervates | sternocleidomastoid muscle, trapezius muscle |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nervus accessorius |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The accessory nerve, also known as the eleventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve XI, or simply CN XI, is a cranial nerve that supplies the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. It is classified as the eleventh of twelve pairs of cranial nerves because part of it was formerly believed to originate in the brain. The sternocleidomastoid muscle tilts and rotates the head, whereas the trapezius muscle, connecting to the scapula, acts to shrug the shoulder.

Traditional descriptions of the accessory nerve divide it into a spinal part and a cranial part.[1] The cranial component rapidly joins the vagus nerve, and there is ongoing debate about whether the cranial part should be considered part of the accessory nerve proper.[2][1] Consequently, the term "accessory nerve" usually refers only to nerve supplying the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, also called the spinal accessory nerve.[3]

Strength testing of these muscles can be measured during a neurological examination to assess function of the spinal accessory nerve. Poor strength or limited movement are suggestive of damage, which can result from a variety of causes. Injury to the spinal accessory nerve is most commonly caused by medical procedures that involve the head and neck.[4] Injury can cause wasting of the shoulder muscles, winging of the scapula, and weakness of shoulder abduction and external rotation.[5]

The accessory nerve is derived from the basal plate of the embryonic spinal segments C1–C6.

Structure

The fibres of the spinal accessory nerve originate solely in neurons situated in the upper spinal cord, from where the spinal cord begins at the junction with the medulla oblongata, to the level of about C6.[1][6] These fibres join together to form rootlets, roots, and finally the spinal accessory nerve itself. The formed nerve enters the skull through the foramen magnum, the large opening at the skull's base.[1] The nerve travels along the inner wall of the skull towards the jugular foramen.[1] Leaving the skull, the nerve travels through the jugular foramen with the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves.[7] The spinal accessory nerve is notable for being the only cranial nerve to both enter and exit the skull. This is due to it being unique among the cranial nerves in having neurons in the spinal cord.[8]

After leaving the skull, the cranial component detaches from the spinal component. The spinal accessory nerve continues alone and heads backwards and downwards. In the neck, the accessory nerve crosses the internal jugular vein around the level of the posterior belly of digastric muscle. As it courses downwards, the nerve pierces through the sternocleidomastoid muscle (approximately 1cm above Erb's point) while sending it motor branches, then continues down until it reaches the trapezius muscle (entering at the junction of the middle and lower third of the anterior border of the trapezius) to provide motor innervation to its upper part.[9]

Nucleus

The fibres that form the spinal accessory nerve are formed by lower motor neurons located in the upper segments of the spinal cord. This cluster of neurons, called the spinal accessory nucleus, is located in the lateral aspect of the anterior horn of the spinal cord, and stretches from where the spinal cord begins (at the junction with the medulla) through to the level of about C6.[1] The lateral horn of high cervical segments appears to be continuous with the nucleus ambiguus of the medulla oblongata, from which the cranial component of the accessory nerve is derived.[8]

Variation

In the neck, the accessory nerve crosses the internal jugular vein around the level of the posterior belly of digastric muscle, in front of the vein in about 80% of people, and behind it in about 20%,[8] and in one reported case, piercing the vein.[10]

Traditionally, the accessory nerve is described as having a small cranial component that descends from the medulla and briefly connects with the spinal accessory component before branching off of the nerve to join the vagus nerve.[1] A study, published in 2007, of twelve subjects suggests that in the majority of individuals, this cranial component does not make any distinct connection to the spinal component; the roots of these distinct components were separated by a fibrous sheath in all but one subject.[6]

Development

The accessory nerve is derived from the basal plate of the embryonic spinal segments C1–C6.[11]

Function

The spinal component of the accessory nerve provides motor control of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.[7] The trapezius muscle controls the action of shrugging the shoulders, and the sternocleidomastoid the action of turning the head.[7] Like most muscles, control of the trapezius muscle arises from the opposite side of the brain.[7] Contraction of the upper part of the trapezius muscle elevates the scapula.[12] The nerve fibres supplying sternocleidomastoid, however, are thought to change sides (Latin: decussate) twice. This means that the sternocleidomastoid is controlled by the brain on the same side of the body. Contraction of the stenocleidomastoid fibres turns the head to the opposite side, the net effect meaning that the head is turned to the side of the brain receiving visual information from that area.[7] The cranial component of the accessory nerve, on the other hand, provides motor control to the muscles of the soft palate, larynx and pharynx.

Classification

Among researchers there is disagreement regarding the terminology used to describe the type of information carried by the accessory nerve. As the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles are derived from the pharyngeal arches, some researchers believe the spinal accessory nerve that innervates them must carry specific special visceral efferent (SVE) information.[13] This is in line with the observation that the spinal accessory nucleus appears to be continuous with the nucleus ambiguus of the medulla. Others consider the spinal accessory nerve to carry general somatic efferent (GSE) information.[14] Still others believe it is reasonable to conclude that the spinal accessory nerve contains both SVE and GSE components.[15]

Clinical significance

Examination

The accessory nerve is tested by evaluating the function of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles.[7] The trapezius muscle is tested by asking the patient to shrug their shoulders with and without resistance. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is tested by asking the patient to turn their head to the left or right against resistance.[7]

One-sided weakness of the trapezius may indicate injury to the nerve on the same side of an injury to the spinal accessory nerve on the same side (Latin: ipsilateral) of the body being assessed.[7] Weakness in head-turning suggests injury to the contralateral spinal accessory nerve: a weak leftward turn is indicative of a weak right sternocleidomastoid muscle (and thus right spinal accessory nerve injury), while a weak rightward turn is indicative of a weak left sternocleidomastoid muscle (and thus left spinal accessory nerve).[7]

Hence, weakness of shrug on one side and head-turning on the other side may indicate damage to the accessory nerve on the side of the shrug weakness, or damage along the nerve pathway at the other side of the brain. Causes of damage may include trauma, surgery, tumours, and compression at the jugular foramen.[7] Weakness in both muscles may point to a more general disease process such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Guillain–Barré syndrome or poliomyelitis.[7]

Injury

Injury to the spinal accessory nerve commonly occurs during neck surgery, including neck dissection and lymph node excision. It can also occur as a result of blunt or penetrating trauma, and in some causes spontaneously.[16][5] Damage at any point along the nerve's course will affect the function of the nerve.[9] The nerve is intentionally removed in "radical" neck dissections, which are attempts at exploring the neck surgically for the presence and extent of cancer. Attempts are made to spare it in other forms of less aggressive dissection.[5]

Injury to the accessory nerve can result in neck pain and weakness of the trapezius muscle. Symptoms will depend on at what point along its length the nerve was severed.[5] Injury to the nerve can result in shoulder girdle depression, atrophy, abnormal movement, a protruding scapula, and weakened abduction.[5] Weakness of the shoulder girdle can lead to traction injury of the brachial plexus.[9] Because diagnosis is difficult, electromyogram or nerve conduction studies may be needed to confirm a suspected injury.[5] Outcomes with surgical treatment appear to be better than conservative management, which entails physiotherapy and pain relief.[16] Surgical management includes neurolysis, nerve end-to-end suturing, and surgical replacement of affected trapezius muscle segments with other muscle groups, such as the Eden-Lange procedure.[16]

Damage to the nerve can cause torticollis.[17]

History

English anatomist Thomas Willis in 1664 first described the accessory nerve, choosing to use "accessory" (described in Latin as nervus accessorius) meaning in association with the vagus nerve.[18]

In 1848, Jones Quain described the nerve as the "spinal nerve accessory to the vagus", recognizing that while a minor component of the nerve joins with the larger vagus nerve, the majority of accessory nerve fibres originate in the spinal cord.[3][19] In 1893 it was recognised that the heretofore named nerve fibres "accessory" to the vagus originated from the same nucleus in the medulla oblongata, and it came to pass that these fibres were increasingly viewed as part of the vagus nerve itself.[3] Consequently, the term "accessory nerve" was and is increasingly used to denote only fibres from the spinal cord; the fact that only the spinal portion could be tested clinically lent weight to this opinion.[3]

See also

Additional images

-

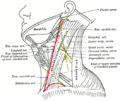

Course and distribution of the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and accessory nerves. The accessory nerve (top left) travels down through the jugular foramen with the other two nerves, and then passes down, usually over the internal jugular vein, to supply the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles

-

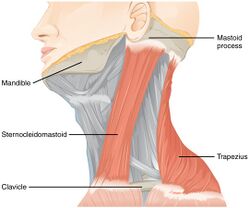

Side of the neck, with accessory nerve seen between the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles

-

The brain and upper spinal cord in a cadaver specimen. The accessory nerve can be seen as a number of rootlets arising from the medulla.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 459.

- ↑ "Spinal Accessory Nerve". Structure of the Human body, Loyola University Medical Education Network. http://www.meddean.luc.edu/lumen/MedED/grossanatomy/h_n/cn/cn1/cn11.htm.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Terence R. Anthoney (1993). Neuroanatomy and the Neurologic Exam: A Thesaurus of Synonyms, Similar-Sounding Non-Synonyms, and Terms of Variable Meanings. Boca Raton: CRC-Press. pp. 69–73. ISBN 0-8493-8631-4.

- ↑ "Iatrogenic accessory nerve injury". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 78 (2): 146–50. 1996. PMID 8678450.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Kelley, Martin J.; Kane, Thomas E.; Leggin, Brian G. (February 2008). "Spinal Accessory Nerve Palsy: Associated Signs and Symptoms". Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 38 (2): 78–86. doi:10.2519/jospt.2008.2454. PMID 18560187.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Is the cranial accessory nerve really a portion of the accessory nerve? Anatomy of the cranial nerves in the jugular foramen". Anatomical Science International 82 (1): 1–7. 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1447-073X.2006.00154.x. PMID 17370444.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Talley, Nicholas (2014). Clinical Examination. Churchill Livingstone. pp. 424–5. ISBN 978-0-7295-4198-5.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Finsterer, Josef; Grisold, Wolfgang (2015). "Disorders of the lower cranial nerves". Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice 6 (3): 377–91. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.158768. PMID 26167022.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 460.

- ↑ "Anatomic relationship between the spinal accessory nerve and the jugular vein: a cadaveric study". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 33 (2): 175–179. 2010. doi:10.1007/s00276-010-0737-y. PMID 20959982.

- ↑ Skórzewska, A; Bruska, M; Woźniak, W (1994). "The development of the spinal accessory nerve in human embryos during 5th week (stages 14 and 15).". Folia Morphologica 53 (3): 177–84. PMID 7883243.

- ↑ Kelley, Martin J.; Kane, Thomas E.; Leggin, Brian G. (February 2008). "Spinal Accessory Nerve Palsy: Associated Signs and Symptoms". Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 38 (2): 78–86. doi:10.2519/jospt.2008.2454. PMID 18560187. ""The upper trapezius elevates, the middle trapezius retracts, and the lower trapezius depresses. In unison, the pri- mary function of the trapezius is to up- wardly rotate the scapula during shoulder elevation, forming a force couple with the serratus anterior"".

- ↑ William T. Mosenthal (1995). A Textbook of Neuroanatomy: With Atlas and Dissection Guide. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. p. 12. ISBN 1-85070-587-9.

- ↑ Duane E. Haines (2004). Neuroanatomy: an atlas of structures, sections, and systems. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-4677-9. https://archive.org/details/neuroanatomyatla00hain.

- ↑ "Muscle Dorso-Fascialis — A Case Report". Journal of the Anatomical Society of India 50 (2): 159–160. 2001.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Martin, Ryan M.; Fish, David E. (2 November 2007). "Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 1 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s12178-007-9000-5. PMID 19468892.

- ↑ Tomczak, K (2013). "Torticollis". Journal of Child Neurology 28 (3): 365–378. doi:10.1177/0883073812469294. PMID 23271760.

- ↑ Davis, Matthew C.; Griessenauer, Christoph J.; Bosmia, Anand N.; Tubbs, R. Shane; Shoja, Mohammadali M. (January 2014). "The naming of the cranial nerves: A historical review". Clinical Anatomy 27 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1002/ca.22345. PMID 24323823.

- ↑ Jones Quain (1848). Elements of Anatomy. 2 (5th ed.). London: Taylor, Walton, and Maberly. p. 812. https://books.google.com/books?id=wSAEAAAAQAAJ.

- Books

- Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice. editor-in-chief, Susan Standring (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. 2008. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

External links

- MedEd at Loyola GrossAnatomy/h_n/cn/cn1/cn11.htm

- lesson6 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- cranialnerves at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (XI)

- Anatomy photo:28:13-0115 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- "11-1". Cranial Nerves. Yale School of Medicine. http://www.yale.edu/cnerves/cn11/cn11_1.html.

|