Biology:Asimina tetramera

| Asimina tetramera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Magnoliales |

| Family: | Annonaceae |

| Genus: | Asimina |

| Species: | A. tetramera

|

| Binomial name | |

| Asimina tetramera Small

| |

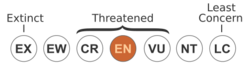

Asimina tetramera, commonly known as the four-petal pawpaw, is a rare species of small tree or perennial shrub endemic to Martin and Palm Beach Counties in the state of Florida.[3] The species is currently listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act and as endangered by the International Union for Conservation. The four-petal pawpaw is part of the Annonaceae family alongside other Asimina species.

A. tetramera grows to between 1 and 3 meters tall with one or more branches.[3] Mature flowers are maroon with some pink streaks and the fruit is yellow-green.[3] It usually has six petals and four sepals.[3]

It lives exclusively in sand pine scrub habitat on the Atlantic Coast Ridge.[4] A. tetramera is pollinated primarily by beetles which feed on tissue on the surface of its stamens and on the inner surface of its petals.[5]

A. tetramera is a fire adapted species.[4] The shrub grows best without the presence of a taller plant canopy shading it.[6] A wildfire may remove these plant canopies to allow for the four-petal pawpaw to flourish.[4] With the return of a shading canopy, the plant growth slows.[4] The removal of the above-ground parts of the plant allows it to grow after a disturbance such as wildfire.

The small range of A. tetramera has been threatened by habitat loss and fire suppression for decades.[2] Human development and disruptive activities has removed suitable land where the species can live.[2] Also, the prevention of wildfires in Florida has limited its ability to grow and reproduce.[2] Work is being done to protect and restore the four-petal pawpaw and its habitat.[4] By protecting existing populations, performing controlled burns, and planting new A. tetramera within its native range, conservationists hope to prevent this rare shrub from going extinct.

Description

The four-petal pawpaw (Asimina tetramera) is a large shrub or small tree. Its fruit is aggregate and yellow-green in color. The fruit is banana-scented when ripe.[4] The seeds of the plant are flat, shiny, and dark brown. The four-petal pawpaw is sensitive to transplantation due to its deep taproot.[7][4]

Size and coloration

It is classified as a large shrub or a small tree.[8] Its growth habit ranges from a small tree or a larger perennial shrub.[4] When sprouting, they are about 2 to 3 centimeters tall from the underground taproot.[5] The plant height ranges from 1 to 3 meters tall.[4] This makes it one of the tallest species of pawpaw.[7]

A mature individual has one or more main stems in the plant.[4] The colors of the branched or unbranched stems vary. This includes red, reddish-brown, brown, grayish-brown, and gray colored bark.[5][8][9] The plant has pale lenticels.[5]

The flowers of the four-pawpaw are maroon with occasional pink streaks.[5] At the start of blooming, they can be seen with cream-colored flowers.[4] The color of the flower changes as it ages. The fruit that the plant produces is yellow-green and aggregate.[9]

Leaf morphology

The leaves of A. tetramera have an oblong shape and alternate in a spiral pattern on the stem. They measure about 5–10 cm in length. The tips of the leaves are usually blunt. The leaf margins of A. tetramera roll under.[7] This means the leaves of the plant have rolled edges.[9] Young leaves are spotted with small reddish hairs. As they age, the leaves turn to a dark green with a smooth surface.[5] The undersides of the leaves are gray-green in color.[9] The undersides are also reticulated as opposed to the smooth top side of the leaf.[5]

Flower structure

A. tetramera has 6 petals split into two sets of three.[7][9] Usually the petals are three-merous, as said before; however, there is evidence of some four-merous flowers in this species.[5] It has four sepals.[9] A. tetramera has a unique number of sepals since other Asimina species only have three.[7] The stamens are arranged in a spiral pattern on the receptacles. The receptacles of the flower have separate carpels.[7][4] The outer petals of the flower are about 1.5 to 3 centimeters long. They are oblong oval shaped.[5]

Life history

Development

A. tetramera grows a deep taproot. The root crown permits the survival of the plant through droughts, wildfires, and other disturbances. If the aboveground parts of the plant are removed, the plant can resprout from the intact roots.[7][4]

Growth rate

A. tetramera is fire adapted and grows at a faster rate when it is in a recently burned environment. Wildfires burn the taller plant canopy that typically shades the A. tetramera. After burning, the plant regenerates at an increased growth rate. This allows for numerous flowers and fruits to grow. The plant's growth rate declines over time as the taller plants take up canopy space again. A. tetramera relies on natural fires which allow the plant to access sunlight. Fire suppression in its habitat has reduced the number of A. tetramera.[4]

Reproductive cycle

The flowers of the four-petal pawpaw open before the parts inside are matured. The stigmas of the flower become receptive to pollen.[4] Following this, the anthers develop to allow pollen release.[5] The four-petal pawpaw is not a self-fertilizing plant.[5] Four-petal pawpaws have cream-colored flowers when they start to bloom. During maturation, the flowers become maroon. Sometimes the flowers are yellow. If the flower is pollinated, the day following fertilization it will lose its petals. If the flower remains unfertilized, the flowers will fall off days after the release of pollen. Pollinated carpels of the flower develop into fruit. The fruits ripen between 2 and 3 months and are greenish-yellow.[3] The number of fruit developed depends on the availability of pollinators.[5]

Timing of reproduction

The best growth occurs in the seasons following a wildfire. This happens after the destruction of the plants shading A. tetramera as well as its own aboveground parts. The new leaves of the four-petal pawpaw first grow in April and then continue into the summer. The flowers bloom from March through July. The peak blooming occurs in April and May. Flowers only occur on the new growths on the plant.[7]

Offspring quality and quantity

A. tetramera grows based on the resources available. The time it takes to flower is correlated with fruit development.[5] More growth and more flowers occur after a disturbance like a wildfire. Best growth occurs when there is a burn the prior spring. Evidence suggests cutting the stem may also promote growth instead of burning. The seeds of A. tetramera have a high oil content in the endosperm. Seed viability is best in new seeds. Old seeds have low viability due to oil loss. After 1–8 months, seedlings appear. The root system develops before the appearance of seedlings. Most seedlings emerge from September through March.[7][4]

Age of dispersal

Seeds are dispersed around A. tetramera. The fruits of the plant are consumed by animals which allows for dispersion. These animals include gopher tortoises, raccoons, and rodents like beach mice.[7][4]

Annual dormancy

Growth stalls in the four-petal pawpaw when it is shaded by other plants. It remains this way until a disturbance removes the plants that outgrow it. The four-petal pawpaw has the ability to remain dormant underground before it resprouts.[5][7][4]

Age-specific mortality rates

It is very long-lived, probably living well over a century, and able to spend much of its time in a dormant state underground before sprouting again.[3]

Ecology

Specialist insect species use A. tetramera to rear larvae. Both Zebra swallowtail butterflies and Asimina webworm moths lay eggs on A. tetramera leaves and the emerging larvae then eat leaves and flowers from the growing plant.[5] Herbivory damages the developing shoots, which stimulates growth in the plant and extends the breeding cycle for the insects.[5]

The shelf fungus Phylloporia frutica attacks A. tetramera at wounded sites near the ground and the mushroom structure emerges from branching points on the plant.[4] The fungus is not fatal to the plant but may decrease flowering and number of produced fruit.[4]

Common fruit-eating animals include gopher tortoises, raccoons, beach mice and other rodents, and other small mammals.[4][10] The seeds of these fruits may be dispersed and buried as they are eaten by animals, but they do not need to be ingested in order to germinate.[4][11]

Pollination

For Asimina species, pollen is released in aggregates as tetrad structures held together by viscin threads.[5] A. tetramera emits a foul odor as it matures and pollen is released. This foul odor is used to mimic the odor of both fermenting fruit and feces in order to diversify the types of pollinators that visit it.[12]

A. tetramera flowers are primarily pollinated by beetles.[5] The 3 inner petals of the flower form a chamber that beetles occupy between the female and male phases of floral development.[13][5] Beetles feed on grooved structures covering the stamen, inner petal tissue, and pollen grains as they are released after maturation.[5] Beetles leave the flower after the petals fall with pollen on their elytra (forewings), legs, and mouth parts which they may transfer to another flower.[5]

Flowers are also pollinated by several types of flies and wasps that are attracted to their foul odor.[5]

Cox (1998) surveyed the two largest known populations of A. tetramera for insect interactions. The zebra longhorn beetle was observed visiting A. tetramera flowers the most. Beetles represented 12 out 17 visitor species.[5]

Habitat

A. tetramera is found exclusively in coastal dune sand pine scrub habitat.[4] Sand pine scrub is defined by dispersed sand pines and patchy openings.[4] Other associated plant taxa include scrub oaks (Quercus myrtifolia, Q. geminata, Q. chapmanii), saw palmetto, rusty lyonia, and other species of shrub.[14] A. tetramera occurs only along the Atlantic Coastal Ridge complex in the excessively-drained quartz sand of the paola classification.[4] The sand pine scrub ecosystem is mediated by frequent fires that historically created disturbance every 10–50 years.[12] These disturbances enhance the structure and complexity of the system for several years by creating gaps in the canopy for colonization of different vegetation types.[4]

A. tetramera is a shade intolerant understory plant.[11][4] It occurs in varying levels of canopy, but it thrives in habitat where it has the most access to light.[4] A. tetramera is easily outcompeted by larger sand pine and oak trees and even saw palmetto shrubs which are less likely to be shaded out.[4] The presence of these frequent fires indicates better quality habitat for A. tetramera even if individuals have remained in a vegetative state for many years.[6] Too much fire, however, can reduce the cover vegetation that is home to rodents which help disperse the seeds.[10]

Range

Coastal dune sand pine scrub communities along the Atlantic Coastal Ridge have been decimated over the past decades and exist as fragmented islands of habitat for A. tetramera.[4] As a result, the range of the shrub is limited to Martin and Palm Beach Counties in the state of Florida.[12]

Conservation

Past and current geographical distribution

The known distribution of A. tetramera has always been small.[15] Past distribution includes only the counties of Martin and Palm Beach in Florida, USA.[15] Today, the distribution remains only in these two counties, but has become more fragmented and sparse over time. Rather than a continuous distribution across the counties, four-petal pawpaw populations exist in small patches within the identified range. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's (USFWS) Five-Year review from 2022, the southernmost population of A. tetramera has disappeared. Therefore, the size of the species’ distribution has shrunk, and the southern tip of the range has shifted about 7.5 miles north.[12]

There are thought to be about 1,400 remaining individuals across an estimated 14 locations.[12] Most are found within Jonathan Dickinson State Park. However, none of the populations are known to have more than 150 individuals each. More than half of the identified populations exist on private land.[16]

Major threats

There are two primary threats to A. tetramera and its habitat: human-induced habitat loss or modification and the reduction of wildfire occurrences.[2] Human-induced habitat loss is caused by human development and disturbance caused by recreational activities.[2] Martin and Palm Beach Counties, where A. tetramera lives, are densely populated.[4] Land is frequently cleared to build new houses or commercial buildings. Because the four-petal pawpaw is an endemic species (meaning it only occurs in a singular, small area), any amount of habitat loss has a great negative impact on its population status. As human population density and activity continue to increase in Florida, suitable habitat for A. tetramera will continue to be lost.[2]

The four-petal pawpaw is a fire-adapted species.[2] Because of this, it relies on wildfires for growth and reproduction (see life history section). Without wildfires, the plant has reduced growth and flowering.[2] Less flowering leads to a reduced chance for the plant to successfully reproduce.[2] This greatly reduces the population's growth rate. When more pawpaws die than are reproduced, the growth rate becomes negative, and population size declines. Natural wildfires also clear out some overstory species (tall trees that usually create a lot of shade).[2] Without these wildfires, the overstory species can overgrow and shade out pawpaws. Too much shade can stunt the growth of the shrub, causing stress which decreases its health.

Modern perceptions of wildfires have created environmental policies that focus on preventing wildfires. Often, wildfires either do not happen or are immediately put out. However, wildfires are a natural and important part of the ecosystem's functions. When human policies quench wildfires, the natural processes needed for four-petal pawpaws to survive and reproduce are lost.

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services listing

The four-petal pawpaw is protected at the state level via the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS). It is labeled as State-endangered under the Regulated Plants Index.[12] This listing provides protection for the plant, but does not directly protect the plant's habitat.

Endangered Species Act listing

Asimina tetramera was first proposed as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) on November 1, 1985.[17] It was officially listed on September 26, 1986, and its protection under the ESA went into effect on October 27, 1986.[18]

The original report proposing A. tetramera endangerment status argued that the species “is threatened by destruction of its habitat or commercial and residential construction, and by successional changes in habitat”. It mentions that the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution was ordered through the ESA to make reports on plant species that may be threatened or endangered. Although A. tetramera was included in the report (in 1975), its proposal to be labeled an endangered species “expired” before it could be approved.[2]

Reasons given for why the four-petal pawpaw should be listed as endangered include:

- (A) Active destruction and disturbance of its habitat/range,

- (D) Inadequate regulation practices, especially in terms of habitat protection, and

- (E) Other threats, such as lack of wildfires to promote sprouting and reproduction.

Sections B and C (overutilization and disease/predation) were not considered as threats to A. tetramera.[2]

Under the ESA, the four-petal pawpaw is protected through rules that protect its critical habitat, the prevention of any activity that would harm the plant or its habitat, the creation of conservation/restoration plans, and funding for such actions.[18]

Five-year reviews

Despite the four-petal pawpaw becoming an endangered species under the ESA in 1986, there have only been three official 5-year reviews for the species: 1991, 2009, and 2022. Each of the first two reviews present no change in status for A. tetramera (the species remains endangered)[12]

The most recent five-year review of Asimina tetramera was released by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in January 2022. It reports a decrease in the total number of populations.[12] In 2009, there were 16 populations on 21 different sites, but only 9 different populations on 14 different sites in 2021. Of the 9 remaining populations, around half are believed to be increasing or stable. This means the remaining half of the populations are declining. The total estimated number of remaining individuals is 1,400. This is lower than the estimated number reported in 2009, at 1,800 individuals.[12]

A chart is provided in the 2022 five-year review which outlines all the sites where four-petal pawpaw populations have been identified.[12] The largest populations are in Jonathan Dickinson State Park (495 individuals in 2006 and “100s” in 2021), Juno Dunes Natural Area South (335 in 2018/2021), and Juno Dunes Natural Area North (302 in 2016).[12] These larger populations all occur on protected land (i.e. state parks).[12]

In regard to threats, the 2022 review identifies continued human development as the biggest threat to A. tetramera habitat.[12] It predicts that habitat loss due to development and land clearing will continue to increase, especially due to human population growth in Martin and Palm Beach Counties, Florida. Other threats listed include inadequate regulations, low reproductive rates, invasive species, and herbicides used against invasive species.[12] It is unclear if climate change effects will impact A. tetramera populations.[12] However, these factors are considered potential threats. Included in climate-change-related potential threats are sea level rise, increased average temperature, changes in precipitation patterns, and more frequent or intense hurricanes.[12] The degree of potential harm of these factors on A. tetramera is varied.[12] Sea level rise is identified as having a high potential for negative impact on A. tetramera because it could cause direct loss of the plants coastal habitat.[12]

Recommendations by the 2022 five-year review for continued management of the four-petal pawpaw include introducing more individuals in protected areas with appropriate habitat conditions.[12] Previous attempts of this practice have not been very successful. The USFWS suggests more research into habitat requirements to increase success rates of this form of management. To address direct habitat destruction, the USFWS argues for increasing resources for habitat maintenance and restoration efforts.[12]

The 2022 review also provides “recommendations for future activities”, which fall into three categories: Recovery Activities, Research/Monitoring, and Outreach/Collaboration.[12] Recovery Activities include collecting A. tetramera seeds for “ex situ” safeguarding, continuing propagation, identifying suitable habitat for introduction, prescribed burns, and careful invasive species management.[12] Research and monitoring recommendations consist of surveying for suitable habitat, continuing (and expanding) monitoring of populations, studying associated pollinators, and analyzing the impacts of climate change on the species.[12] Proposed outreach and collaboration activities include partnering county, state, and federal agencies in research and conservation practices, publicizing information about the species and its conservation (i.e. through media), and engaging youth and volunteers in conservation and monitoring projects.[12]

Species Status Assessment

There is currently no Species Status Assessment available for Asimina tetramera (as of 2022).

Recovery Plan

The four-petal pawpaw's current recovery plan is laid out under the South Florida Multi-Species Recovery Plan (MSRP),[4] which was issued on May 18, 1999. The plan was most recently amended in September 2019.[16] In the South Florida MSRP, A. tetramera was included amongst 8 mammals species, 13 bird species, 10 reptile species, 2 invertebrate species, and 34 other plant species.[4]

The two primary recommended recovery actions are prescribed (controlled) burning and protection of remaining habitat.[4] Prescribed burns and biomass reduction (cutting back plants) are currently a management technique used in Jonathan Dickinson State Park.[4][16][10] Numerous species-level recovery actions are presented by the USFWF under the Recovery Plan.[16] The plan suggests continuously surveying the two counties where A. tetramera has been identified. The goal is to record any changes in population trends and species range. Previously unknown sites or sub-populations may be found as surveys continue.[16] Another plan is creating and maintaining a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) database of A. tetramera. The database would contain information on plant locations, plant/population status, and population sizes. This would allow for convenient visualization of changing trends in four-petal pawpaw populations. Other plans include protecting existing populations, using “local or regional planning to protect habitat”, and continuing research on life history characteristics. “Ex situ”, or “off site”, conservation is also mentioned as a recovery action.[16] In this approach, the plants are grown in controlled conditions, including greenhouses or protected areas. By having some controlled four-petal pawpaw plants, seed can be collected and genetic diversity can be maintained.[16] The plan also makes note of the importance of enforcing protective measures. Taking, removing, or intentionally damaging the plant is banned. According to the Recovery Plan, offenders of such actions should be punished.[16]

2019 Recovery Plan amendment

The recovery plan was amended in 2019.[16] The amendment added delisting criteria for the four-petal pawpaw because the original plan only included “downlisting” criteria.[16] Delisting guidelines act as a set of goals from which conservation plans can be made. By abiding by these goals, the chance of A. tetramerea populations surviving and/or growing is increased. The delisting criteria includes:

- At least 25 populations are stable or growing

- The populations meeting the first criterion are within the habitat of historical range (sand pine scrub).

- There are conservation or management practices in place that ensure the habitat remains, allowing for the growth of pawpaw populations to continue or remain steady.[16]

This amendment also mentions that the population declines of A. tetramera may have caused a loss in genetic diversity. This raises another point of concern because genetic diversity loss makes it easier for populations to be wiped out by major events (i.e. hurricanes, disease outbreak). Management practices are emphasized as an important recovery plan. It specifically mentions controlled burning, controlling non-native or invasive species, and restoring the scrub pine habitats as was to work towards A. tetramera recovery.[16]

References

- ↑ Treher, A. (2022). "Asimina tetramera". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T30379A152335178. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T30379A152335178.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/30379/152335178. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Proposed Endangered and Threatened Status for Three Florida Shrubs". Federal Register 50: 45634–45638. 1985-11-01. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1985-11-01/pdf/FR-1985-11-01.pdf#page=52.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 "Asimina tetramera". https://irlspecies.org/taxa/index.php?quicksearchselector=on&quicksearchtaxon=asimina+tetramera&taxon=&formsubmit=Search+Terms.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 4.31 4.32 4.33 4.34 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service South Florida Field Office (1999-05-18). "Multi-Species Recovery Plan: Asimina tetramera". http://www.fws.gov/verobeach/msrppdfs/fourpetal.pdf.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 Cox, Anne Cheney (1998-11-05). Comparative reproductive biology of two Florida pawpaws asimina reticulata chapman and asimina tetramera small. doi:10.25148/etd.fi14061532. http://dx.doi.org/10.25148/etd.fi14061532.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Roberts, Richard E (2000). "SAND PINE SCRUB VEGETATION RESPONSE TO TWO BURNING AND TWO NON-BURNING TREATMENTS". https://talltimbers.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/114-RobertsandCox2000_op.pdf.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 Nelson, G (1996). The Shrubs and Woody Vines of Florida. Sarasota, FL.: Pineapple Press, Inc..

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1998). "Asimina tetramera". https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/30379/9542441.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Walker, James W. (1971). "Pollen Morphology, Phytogeography, and Phylogeny of the Annonaceae". Contributions from the Gray Herbarium of Harvard University 202 (202): 1–130. doi:10.5962/p.272704.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Center for Plant Conservation. "National Collection Plant Profile: Asimina tetramera". http://www.centerforplantconservation.org/collection/cpc_viewprofile.asp?CPCNum=315.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kral, Robert (1983). A report on some rare, threatened, or endangered forest-related vascular plants of the South. Atlanta, Ga.: USDA Forest Service, Southern Region. pp. 448–451.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 12.17 12.18 12.19 12.20 12.21 12.22 12.23 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Florida Ecological Services Field Office (January 2022). "Four-petal pawpaw (Asimina tetramera) 5-year Review: Summary and Evaluation". https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/tess/species_nonpublish/3628.pdf.

- ↑ Gottsberger, Gerhard (October 2014). "Basal Angiosperms and beetle pollution". Conference: XI Congreso Latinoamericano de Botánica e LXV Congresso Nacional de Botânica. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299980423.

- ↑ Schmalzer, Paul A.; Boyle, Shannon R.; Swain, Hilary M. (1999). "Scrub Ecosystems of Brevard County, Florida: A Regional Characterization". Florida Scientist 62 (1): 13–47. ISSN 0098-4590. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24320960.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Small, John K. (1926). "A New Pawpaw from Florida.". Torreya 26 (3): 56. ISSN 0096-3844. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40596457.

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 South Florida Ecological Services Office staff (March 2019). "Recovery Plan for the endangered Asimina tetramera (Four-petal pawpaw) DRAFT AMENDMENT 1". https://ecos.fws.gov/docs/recovery_plan/Four%20Petal%20PawPaw%20Recovery%20Plan%20Amendment.pdf.

- ↑ "ECOS: Species Profile". https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/species/3461.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Status for Three Florida Shrubs". Federal Register 51: 34415–34418. 1986-09-12. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1986-09-26/pdf/FR-1986-09-26.pdf#page=1.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q4806999 entry

|