Biology:Creation of life from clay

From HandWiki

Short description: Miraculous birth theme in multiple mythologies

The creation of life from clay is a miraculous birth theme that appears throughout world religions and mythologies.

Religion and folklore

- According to Genesis 2:7 "And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul".

- According to the Qur'an (Qur'an 23:12),[1][2] God created man from clay.

- In Jewish folklore, a golem (Hebrew: גולם) is an animated anthropomorphic being that is created entirely from inanimate matter, usually clay or mud.[3]

- In Sumerian mythology, the gods Enki or Enlil create a servant of the gods, humankind, out of clay and blood (see Enki and the Making of Man). In another Sumerian story, both Enki and Ninmah create humans from the clay of the Abzu, the fresh water of the underground. They take turns in creating and decreeing the fate of the humans.[4]

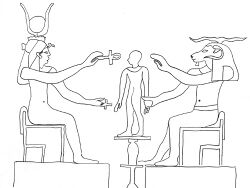

- According to Egyptian mythology, the god, Khnum, creates human children from clay before placing them into their mother's womb.[5][6]

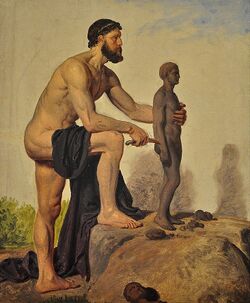

- In Greek mythology, according to Pseudo-Apollodorus,[7] Prometheus molded men out of water and earth. Near the town of Panopeus, the remaining used clay was allegedly still present in historical times as two cart-sized rocks that smelled like a human body.[8][9] Myths about Prometheus were inspired by Near Eastern Myths about Enki.[10]

- Also in Greek mythology, Prometheus moulds a clay statue of Minerva, the goddess of wisdom to whom he is devoted, and gives it life from a stolen sunbeam.[11]

- Pandora, from Greek mythology, was fashioned from clay and given the quality of “naïve grace combined with feeling”.[12]

- In Zoroastrian mythology, first the primordial ox, Gavaevodata, and subsequently the primordial human, Gayomart are created from mud by the supreme deity Ahura Mazda.

- In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu is created by the goddess Aruru out of clay to be a partner for Gilgamesh, "mighty in strength".

- According to Chinese mythology, (see Chu Ci and Imperial Readings of the Taiping Era), Nüwa molded figures from the yellow earth, giving them life and the ability to bear children.[13]

- In the Babylonian creation epic Enuma Elish, the goddess, Ninhursag, created humans from clay.

- According to Hindu mythology, Parvati, the mother of Ganesha, created her son from clay and turned the clay into flesh and blood.

- According to some Laotian folk religion, there are stories of humans created from mud or clay.

- In Hawaiian tradition, the first man was composed of muddy water and his female counterpart was taken from his side parts (story may be partially or entirely christianized).[14]

- The Yoruba culture holds that the god Obatala, likewise, created the human race from clay.[15]

- The Māori people believe that Tāne Mahuta, god of the forest, created the first woman out of clay and breathed life into her.

- According to Inca mythology, the creator god, Viracocha, formed humans from clay on his second attempt at creating living creatures.[16]

- In Norse mythology, humans are made from sand in tree trunks.[17]

- In the Korean Seng-gut narrative, humans are created from red clay.

- According to the beliefs of some Indigenous Americans, the Earth-maker formed the figure of many men and women, which he dried in the sun and into which he breathed life.[18]

- In the K'iche' creation story Popol Vuh, the first humans are made of clay, although they soak up water and disintegrate.

- Central Asian mythology, including Altaic and Mongolian, have stories about how the god Ulgen created the first man, Erlik, from clay floating on the surface of water. [19] [20]

- Woyengi, in Ijaw tradition, created humans from earth that fell from the sky before granting them identities.

- The Ainu historically believed that Kamui built the Ainu on the back of a giant fish using clay, sticks, and water.[21]

- The Birhor of India believe that a leech was responsible for bringing the creator god mud which would later be made into humans.[22]

- The Gondi people believe that Nantu (the moon) was made of mud that Kumpara spat onto his son.[23]

- The Efé people have a creation story in which the first man was made of clay and skin.[24]

- According to Malagasy mythology, the sky deity Zanahary and the earth deity Ratovantany created the Malagasy people by breathing life into clay dolls.[25]

- Tane, in Polynesian mythology, created the original woman from red clay.[26]

- The Garo people in India believe that a beetle gave clay to the creator god Tatara-Rabuga, who made humanity from it.[27]

- The Aymaran creation myth involves the making of humans from clay.[28]

- The Songye people have a creation myth involving two gods, Mwile and Kolombo, creating humans out of clay as part of a rivalry.[29]

- Buryatian mythology has the god Sombov create humans from clay and wool.[30]

- Some of the Dinka of Sudan believe Nhialac, the creator, formed the humans Abuk and Garang from clay. The clay was put into pots to grow, and eventually came out as fully-grown adults. Other narratives attribute the creation of humanity to Nhialac blowing his nose or believe that humans came from the sky and were placed upon a river as full-grown adults. [31]

- The Dogon people believe the Earth goddess was made when Amma flung earth into the primordial void.[32]

- Ara and Irik, two bird spirits from Bornean myth, created humans from clay and the sound of their own voices.

- Iñupiat mythology has Raven create a human out of clay, who would later become Tornaq, the first demon.[33]

- Andamanese Mythology women were fashioned from clay (while the men emerged from split bamboo).[34][35]

- In Vietnamese mythology, the Ngọc Hoàng and the Twelve Bà mụ created people from clay.[36] [37]

- In Skaldskaparmal, the god Thor encounters a giant named Mokkurkalfe (sv), who was made from clay.[38]

In science

- The role of clay minerals in abiogenesis was suggested in a 2013 paper titled Clay Minerals and the Origin of Life.[39]

In fiction

- The superheroine Wonder Woman was sculpted from clay by her mother Hippolyta and given life by the Greek gods.[40][41][42]

References

- ↑ Q23:12, 50+ translations, islamawakened.com

- ↑ [23:12–15]

- ↑ "Golem" (in en). https://www.jmberlin.de/en/topic-golem.

- ↑ The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ Leeming, D. A. (2008). The Oxford illustrated companion to world mythology. New York: Tess Press.

- ↑ Bibliotheca 1.7.1

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece 10. 4. 4

- ↑ Dougherty, C. (2006). Prometheus. Abingdon: Routledge.

- ↑ West, S. (1994). Prometheus Orientalized. Museum Helveticum, 51(3), 129-149.

- ↑ David Jonathan Hildner, Reason and the Passions in the Comedias of Calderón, John Benjamin’s Publishing Co. 1982, pp.67-71

- ↑ Colardeau, Charles Pierre (1775). "Les hommes de Promethée, poëme. Par m. Colardeau". https://books.google.com/books?id=xOrbH_P8MBMC.

- ↑ Handbook of Chinese Mythology, by Lihui Yang et al., Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 170–172.

- ↑ Abraham Fornander; Thomas Thrum (1920). Fornander Collection of Hawaiian Antiquities and Folk-lore. Bishop Museum Press. p. 335. https://books.google.com/books?id=j8MqAQAAIAAJ&q=Kumuhonua.

- ↑ "Obatala is Tempted with Palm Wine". https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100243353.

- ↑ Steele, P. R., & Allen, C. J. (2004). Handbook of inca mythology. In Handbook of Inca mythology (pp. 53-54). Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO.

- ↑ Hultgård, Anders (2006). "The Askr and Embla Myth in a Comparative Perspective". In Andrén, Anders; Jennbert, Kristina; Raudvere, Catharina (editors).Old Norse Religion in Long-term Perspectives. Nordic Academic Press. ISBN:91-89116-81-X

- ↑ Almost Ancestors: The First Californians by Theodora Kroeber and Robert F. Heizer

- ↑ "Altaic Mythology". https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095405797.

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link p. 10-11

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link p. 95-96

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link p. 312

- ↑ Leeming, David Adams. Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2010. External link

- ↑ Radcliffe-Brown, Alfred Reginald. The Andaman Islanders: A study in social anthropology . 2nd printing (enlarged). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1933 [1906]. p. 192

- ↑ Witzel, Michael E.J. (2012). The Origin of The World's Mythologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 309-312

- ↑ Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. 2009. p. 394. ISBN 978-0195387087. https://books.google.com/books?id=iPrhBwAAQBAJ&dq=Vietnamese+creation+myths&pg=PA394.

- ↑ "Thần thoại Ông Trời - Thần thoại Việt Nam" (in vi). TruyệnXưaTíchCũ.com. http://truyenxuatichcu.com/than-thoai-viet-nam/than-thoai-ong-troi.html.

- ↑ Gemynthe, Finn (2023) (in da). Jætternes Saga. Vor ældste slægtshistorie. Lindhardt og Ringhof. p. 269. ISBN 978-87-28-42752-1. https://www.google.se/books/edition/J%C3%A6tternes_Saga_Vor_%C3%A6ldste_sl%C3%A6gtshisto/3tjXEAAAQBAJ?hl=sv&gbpv=1&dq=mokkurkalfe&pg=PA269&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ Brack, A. (2013-01-01), Bergaya, Faïza; Lagaly, Gerhard, eds., "Chapter 10.4 - Clay Minerals and the Origin of Life", Developments in Clay Science, Handbook of Clay Science (Elsevier) 5: pp. 507–521, doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-098258-8.00016-X, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978008098258800016X, retrieved 2019-08-19

- ↑ Wonder Woman: The Complete History by Les Daniels, published by Chronicle in 2000, ISBN:0811829138

- ↑ The Secret History of Wonder Woman by Jill Lepore, published by Knopf in 2015, ISBN:0804173400

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes by Michael L. Fleischer, published in 1976, ISBN:9780020800804

Further reading

- Bellows, Henry Adams (Trans.) (1936). The Poetic Edda. Princeton University Press. New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Leeming, D. A. (2008). The Oxford illustrated companion to world mythology. New York: Tess Press.

- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (2006). The Prose Edda. Penguin Classics. ISBN:0-14-044755-5

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1975). Scandinavian Mythology. Paul Hamlyn. ISBN:0-600-03637-5

- Dronke, Ursula (Trans.) (1997). The Poetic Edda: Volume II: Mythological Poems. Oxford University Press. ISBN:0-19-811181-9

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN:0-19-283946-2

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN:0-19-515382-0

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN:0-304-34520-2

- Puhvel, Jaan (1989 [1987]). Comparative Mythology. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN:0-8018-3938-6

- Schach, Paul (1985). "Some Thoughts on Völuspá" as collected in Glendinning, R. J. Bessason, Heraldur (Editors). Edda: a Collection of Essays. University of Manitoba Press. ISBN:0-88755-616-7

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer. ISBN:0-85991-513-1

- Thorpe, Benjamin (Trans.) (1907). The Elder Edda of Saemund Sigfusson. Norrœna Society.

- Thorpe, Benjamin (Trans.) (1866). Edda Sæmundar Hinns Frôða: The Edda of Sæmund the Learned. Part I. London: Trübner & Co.

- Steele, P. R., & Allen, C. J. (2004). Handbook of Inca mythology. In Handbook of Inca mythology (pp. 53-54). Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO.

|