Biology:Ephemera

Ephemera are transitory creations which are not meant to be retained or preserved. Its etymological origins extends to Ancient Greece , with the common definition of the word being: "the minor transient documents of everyday life". Ambiguous in nature, various interpretations of ephemera and related items have been contended, including menus, newspapers, postcards, posters, sheet music, stickers, and valentines.

Since the printing revolution, ephemera has been a long-standing element of everyday life. Some ephemera are ornate in their design, acquiring prestige, whereas others are minimal and notably utilitarian. Virtually all conceptions of ephemera make note of the matter's disposability.

Ephemera has long been collected by the likes of families, hobbyists and curators, with certain instances of ephemera intended to be collected. Literature by collectors and societies has contributed to a greater willingness to preserve ephemera, which is now ubiquitous in archives and library collections. Ephemera has seen academic interest as a beneficial prospect to humanities and for its own sake, illustrating or providing insight into diverse matters, such as those of a sociological, cultural, or anthropological background.

Etymology and categorisation

The etymological origin of Ephemera (ἐφήμερα) is the Greek epi (ἐπί) – "on, for" and hemera (ἡμέρα) – "day". This combination generated the term ephemeron in neuter gender; the neuter plural form is ephemera, the source of the modern word, which can be traced back to the works of Aristotle.[1] The word is both plural and singular.[2] The initial sense extended to the mayfly and other short-lived insects and flowers, belonging to the biological order Ephemeroptera.[3] In 1751, Samuel Johnson used the term ephemerae in reference to "the papers of the day" – and is frequently cited as the term's creator.[4] This application of ephemera has been cited as the first example of aligning it with transient prints.[5] Ephemeral, by the mid-19th century, began to be used to generically refer to printed items.[4] Ephemera and ephemerality have mutual connotations of "passing time, change, and the philosophically ultimate vision of our own existence".[6] The degree to which ephemera is ephemeral is due in part to the value bestowed upon it and the passage of time has seen the ephemerality of certain ephemera decrease generally.[7][8] Comic books, for example, were once considered ephemera; however, that perception later faded.[9]

Ephemera, ambiguous in nature, has been noted to have had a history of assorted applications, the presently most common definition being: "the minor transient documents of everyday life".[4][10] This definition ascribes ephemera's presence within the greater context of printed materials: ostensibly trivial mundanity.[4] "[E]veryday life" establishes a connection to popular culture and social history; ephemera is an important aspect of said life, which, according to Henry Jenkins, showcases the immaterial nature of culture arising in daily life.[11][12][13] Rick Prelinger noted that with greater value granted to ephemera, thus reducing ephemerality, the general definition may itself be short-lived.[14]

With a virtual consensus between librarians that ephemera is "difficult", categorisation has burdened the field of library science and is similarly difficult for historiography due to the ambiguity of ephemera.[15][4][16] A piece of ephemera's purpose, field of use and geography are among the various elements relevant to its categorisation.[17] Challenges pertaining to ephemera include determining its creator, purpose, date and location of origin and impact thereof.[18][19] Determining its worth in a present context, distinct from its perhaps obscured purpose, is also of interest.[20]

The breadth of printed ephemera is vast and varied, often eluding simple definition.[21][22] Librarians often conflate ephemera with grey literature whereas collectors often broaden the scope and definition of ephemera.[23][24] José Esteban Muñoz considered the characteristics of ephemera to be subversion and social experience; Alison Byerly described ephemera as the response to cultural trends.[25][26] Wasserman, who defined ephemera as "objects destined for disappearance or destruction", categorised the following as ephemera:[27]

- air transport labels

- bank checks

- bingo cards

- bookmarks

- broadsides

- bus tickets

- catalogs

- envelopes

- flyers

- maps

- menus

- newspapers

- pamphlets

- paper dolls

- postcards

- receipts

- sheet music

- stamps

- theater programs

- ticket stubs

- valentines

Further items that have been categorised as ephemera include: posters, album covers, meeting minutes, buttons, stickers, financial records and personal memorabilia; announcements of events in a life, such as a birth, a death, a graduation or marriage, have been described as ephemera.[11][16][28] Textual material, uniformly, could be considered ephemera.[1] Artistic ephemera include sand paintings, sculptures composed of intentionally transient material, graffiti, and guerrilla art.[29] Historically, there has been various categories of ephemera.[30][31] Genres may be defined by function or encompass and detail a specific item.[32][30] Over 500 categories are listed in The Encyclopedia of Ephemera, ranging from the 18th to 20th century.[26][33]

Forms

There is scarcely a subject that has not generated its own ephemera.[34]

— Rickards and, the librarian, Julie Anne Lambert

Printed ephemera

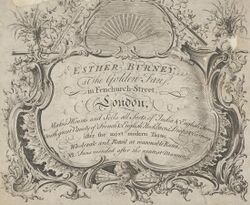

Commonly, printed ephemera is seen to not exceed "more than thirty-two pages in length", although some understandings are more broadly encompassing.[35][36][37][lower-alpha 1] Ephemera is chiefly observed as single page materials, with variance and repeat characteristics.[11][38] The material usage of printed ephemera is very often minimal and much are without art, although a distinct design lexicon can be found in pieces.[1][34] Early ephemera, functionally monochromatic and predominantly textual, indicates a greater access to printing from common people and later cheap photography.[39][40][41] 17th century ephemera incorporated administrative elements and more visuals.[42][43] Advertising and information are among the primary elements of ephemera; design elements, which are typically indicative of the period of origin, such as the Renaissance, likely changed in accordance to higher literacy rates.[11]({{{1}}}, {{{2}}})[44][lower-alpha 2] The prose of ephemera could range from pithy to relatively long (~400 words, for example).[46] By the 19th century, color printing was present, as were vivid, creative, innovative and ornate design, due to the incorporation of lithography.[44][47] The modern ephemera of duplicating machines and photocopiers are chiefly informative.[1] Ephemera's "generic legibility" was achieved through the use of visuals, a quality that was significantly democratised by ephemera.[40][48]

Various forms of printed ephemera deteriorate quickly, a key element in definitions of ephemera. Although broad, pre-19th century ephemera has seldom survived.[4][5][49][45] Much of ephemera was not intended to be disposed of.[8] Assignats saw widespread contempt on account of their low-quality, endangering their survival rate.[50] The temperance movement produced ubiquitous ephemera; some printed ephemera have had production quantities of millions, although quantifying the matter is often reliant upon limited yet vast approximation.[51][16][52][lower-alpha 3] Such temperance ephemera was prominent enough to elicit contemporaneous sentimentality and disdain.[54] By this point, ephemera was printed by various establishments, having likely become a major element of some.[39]

The mid-15th century has been identified as the origin of ephemera, following the Printing Revolution.[5][55] Ephemera, such as religious indulgences, were significant in the early days of printing.[6][55] The first mass produced ephemera is presumed to be a variant of indulgences (~1454/55).[56] Demand for ephemera corresponded with an increasing scale of towns whereupon they were commonly dispersed on streets.[38][57] Ephemera has functioned as a substantial means of disseminating information, evident in public sectors such as tourism, finance, law and recreation and has "aided the proliferation of print media as an exchange of information".[58][59] In their times, ephemera has been used for documentation, education, belligerence, critique and propaganda.[60][61][62][63][64][lower-alpha 4]

Lottery tickets, playbills and trade cards have been among the most prominent ephemera of eras, such as the Georgian and Civil War eras.[66][67] Panoramic paintings were a far-reaching class of ephemera, few remaining as a result.[68] Junk mail is a contemporary example of prominent ephemera.[59] Ephemera's mundane ubiquity is a relatively modern phenomenon, evidenced by Henri Béraldi's amazed writings on their proliferation.[69] Ubiquitous descriptions of printed ephemera have extended back to the 1840s and by the turn of the century, a time in which a deluge of ephemera had become commonplace, "readers [were] defined by their relationship with print ephemera".[70][71][72] Discussing an increase in ephemera by the mid-19th century, E.S Dallas wrote that new etiquette had been introduced, thus "a new era" was to follow, espousing the impression that authorship and literature were no longer hermetic.[73]

Digital ephemera

In 1998, librarian Richard Stone wrote that the internet "can be seen as the ultimate in ephemera with its vast amount of information and advertising which is extremely transitory and volatile in nature, and vulnerable to change or deletion".[22] Multiple academics have described digital ephemera as being possibly more vulnerable than traditional forms.[49][74] Internet memes and selfies have been described as forms of ephemera and various modern print ephemera features a digital component.[75][76] Commonly printed ephemera increasingly only manifests digitally.[77] The Tate Library defines "e-ephemera" as the digital-born content and paratext of an email, typically of a promotional variety, produced by cultural institutions; similar in nature, monographs, catalogues and micro-sites are excluded, per being considered e-books.[75] Websites, such as those of an administrative nature, have seen description as ephemera.[78][79] The likes of Instagram feature accounts dedicated to displaying graphically-designed ephemera.[80]

Digital ephemera is of comparable nature to printed ephemera, although it is even more prevalent and subject to altering perceptions of ephemera.[77][81][82] Holly Callaghan of the Tate Library noted a proliferation of "e-ephemera"; an increased reliance upon this form of ephemera has engendered concern, with note to later accessibility and a difficultly to those outside of the intended recipients.[75][83][84] Citing ostensibly infinite digital storage, Wasserman said that the category, ephemera, may cease to exist, its contents have being ultimately preserved.[85]

Collecting

thumb|20th-century ephemera from the UK |alt=British Ministry of Health poster. Ephemera has long been substantially collected, both with and without intention, presevering what may be the only remaining reproductions.[21][86][87][88] Victorian families pasted their collections of ephemera, acquiring the likes of scraps and trade cards, in scrapbooks whereas Georgian curators thoroughly archived ephemera.[66][89][90] It was a private endeavour, with little outward cultural presence, although an eminent interpersonal function.[91] Cigarette cards were widely collected, by-design.[92][93][lower-alpha 5]

Contemporarily, institutions have attempted to preserve digital ephemera, although problems may exist in regards to scope and interest.[26][75][94] Ephemera has been considered for curation since the 1970s, due in part to collectors, at which point societies, professional associations and publications regarding ephemera arose.[4][95][96] Although ephemera is a global occurrence, interest is chiefly present in Britain and America.[34]({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) Ephemera collections can be idiosyncratic, sequential and difficult to peruse.[26][97]

Multiple scholars articulated a connection to the past, such as nostalgia, as a key motivation for ephemera collecting.[26][98][87][99] Such a connection has been described as evocative and atmospheric; the memory as collective and cultural; the nostalgia as populist and the ephemera associated with melancholy.[100][22][55][88][101] Aesthetics, academic advancement and existential ephemerality have also been seen as motivation.[87][102][103]

Academia

The study of print ephemera has seen much contention; various viewpoints and interpretations have been proposed from scholars, with comparisons to folklore studies and popular culture studies, due to the invoking of "remembrance and echoed retellings" and contending that which is more prestigious, respectively.[10][22][104] Literature around ephemera concern its production, varieties: trade cards, broadside ballads, chapbooks, almanacs, and newspapers; scholars predominately examine ephemera post-19th century due to greater quantities thereof.[38][57][105] A significant amount of scholars have been collectors, archivists and amateurs, particularly at the inception of ephemera studies, a now burgeoning academic field.[37][106][107] Digitisation of ephemera has provided accesiblity and spurred renewed interest, following the "few writings" present at the start of the 21st century.[92][108][109]

As a source, ephemera has been widely accepted.[55] Ephemera has been credited with illustrating social dynamics, including daily life, communication, social mobility and the enforcement of social norms.[1][55] Furthermore, varied cultures from differing groups can be assessed via ephemera.[1][18][33][55][110][lower-alpha 6] Ephemera, to Rickards, documents "the other side of history...[which] contains all sorts of human qualities that would otherwise be edited out".[106]

See also

- Found Footage Festival

- Prelinger Archives

- The Show with No Name

- Ephemeral

- Ephemeris

Notes

- ↑ A qualifier from the National Library of Australia, devised in 1992, virtually excluded material of more than five pages.[22]

- ↑ Display typefaces were an advertising component present prominently in 19th-century ephemera.[45]

- ↑ Ephemera relating to beer, wine and drinking is vast and developed in accordance with drinking movements.[53]

- ↑ Soon after, political propaganda arose as a category of ephemera.[65]

- ↑ In an overview of ephemera, Rickards and Lambert wrote that the specification of cigarette cards as collectable means they should not be classified as ephemera, though rarely is this distinction acknowledged.[34]

- ↑ Following the California Gold Rush of 1849, by means of visual ephemera, the citizens of San Francisco, regardless of race or class, "were exposed to one another".[111]

References

- Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Young, Timothy G. (2003). "Evidence: Toward a Library Definition of Ephemera". RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 4 (1): 11–26. doi:10.5860/rbm.4.1.214. ISSN 2150-668X.

- ↑ Solis-Cohen, Lisa (April 4, 1980). "Ephemera Society is Group Devoted to Throwaways". Bangor Daily News. https://www.newspapers.com/image/665639718/?terms=ephemera&match=1.

- ↑ Wasserman 2020, p. 2.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Garner, Anne (2021). "State of the Discipline: Throwaway History: Towards a Historiography of Ephemera". Book History 24 (1): 244–263. doi:10.1353/bh.2021.0008. ISSN 1529-1499. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/788356.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Russell, Gillian (2014). "The neglected history of the history of printed ephemera" (in English). Melbourne Historical Journal 42 (1): 7–37. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&issn=00766232&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA394113310&sid=googleScholar&linkaccess=abs.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Roylance, Dale (1976). "Graphie Americana: The E. Lawrence Sampter Collection of Printed Ephemera". The Yale University Library Gazette 51 (2): 104–114. ISSN 0044-0175. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40858619.

- ↑ Pecorari, Marco (2021). Fashion Remains: Rethinking Ephemera in the Archive. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 4. ISBN 9781350074774.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Eliot & Rose 2019, p. 633.

- ↑ West, Joel (2020). The Sign of the Joker: The Clown Prince of Crime as a Sign. Brill. pp. 31. ISBN 978-90-04-40868-5. OCLC 1151945452. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1151945452.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Dugaw, Dianne (2020). "Transcendent Ephemera: Performing Deep Structure in Elegies, Ballads, and Other Occasional Forms". Eighteenth-Century Life 44 (2): 17–42. doi:10.1215/00982601-8218591. ISSN 1086-3192. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/758817.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Anghelescu, Hermina G. B. (2001). "A Bit of History in the Library Attic". Collection Management 25 (4): 61–75. doi:10.1300/j105v25n04_07. ISSN 0146-2679. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/j105v25n04_07.

- ↑ Stein, Daniel; Thon, Jan-Noël, eds (2015). From Comic Strips to Graphic Novels: Contributions to the Theory and History of Graphic Narrative. De Gruyter. pp. 310. ISBN 9783110427660.

- ↑ Stone 2005, p. 7.

- ↑ Hediger, Vinzenz, ed (2009). Films that Work: Industrial Film and the Productivity of Media. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 51. ISBN 978-90-8964-013-0. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt45kdjb.

- ↑ McDowell, Paula (2012). "Of Grubs and Other Insects: Constructing the Categories of "Ephemera" and "Literature" in Eighteenth-Century British Writing". Book History 15 (1): 48–70. doi:10.1353/bh.2012.0009. ISSN 1529-1499. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/488252.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Russell, Gillian (2018). "Ephemeraphilia" (in en). Angelaki 23 (1): 174–186. doi:10.1080/0969725x.2018.1435393. ISSN 0969-725X. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080/0969725X.2018.1435393.

- ↑ Massip, Catherine (2020-10-01), Watt, Paul; Collins, Sarah; Allis, Michael, eds., "Ephemera" (in en), The Oxford Handbook of Music and Intellectual Culture in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford University Press): pp. 168–188, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190616922.013.8, ISBN 978-0-19-061692-2, http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190616922.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780190616922-e-8, retrieved 2021-12-11

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Reichard, David A. (2012). "Animating Ephemera through Oral History: Interpreting Visual Traces of California Gay College Student Organizing from the 1970s". Oral History Review 39 (1): 37–60. doi:10.1093/ohr/ohs042. ISSN 1533-8592. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/471290.

- ↑ Weaver 2010, p. 6.

- ↑ Eliot & Rose 2019, p. 634.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Russell, Gillian (2015). "Sarah Sophia Banks's Private Theatricals: Ephemera, Sociability, and the Archiving of Fashionable Life". Eighteenth-Century Fiction 27 (3): 535–555. doi:10.3138/ecf.27.3.535. ISSN 1911-0243. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/584625.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Stone, Richard (1998). "Junk mail: Printed ephemera and preservation of the everyday". Journal of Australian Studies 22 (58): 99–106. doi:10.1080/14443059809387406. ISSN 1444-3058. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443059809387406.

- ↑ Marcum, James W. (2006). "Ephemeral Knowledge in the Visual Ecology". Counterpoints 231: 89–106. ISSN 1058-1634. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42978851.

- ↑ Eliot & Rose 2019, p. 637.

- ↑ Muñoz, José Esteban (1996-01-01). "Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts". Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 8 (2): 5–16. doi:10.1080/07407709608571228. ISSN 0740-770X. https://doi.org/10.1080/07407709608571228.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Byerly, Alison (2009). What not to save: The future of ephemera.. pp. 45–49. http://web.mit.edu/comm-forum/legacy/mit6/papers/Byerly.pdf.

- ↑ Wasserman 2020, p. 2, 236.

- ↑ Ann, Cvetkovich (2003). An Archive of Feelings. Duke University Press. pp. 243. ISBN 978-0-8223-8443-4. OCLC 1139770505. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1139770505.

- ↑ London, Justin (2013). "Ephemeral Media, Ephemeral Works, and Sonny Boy Williamson's "Little Village"". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 71 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6245.2012.01540.x. ISSN 0021-8529. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6245.2012.01540.x.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Andrews, Martin J. (2006). "The stuff of everyday life: a brief introduction to the history and definition of printed ephemera" (in en). Art Libraries Journal 31 (4): 5–8. doi:10.1017/S030747220001467X. ISSN 0307-4722. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/art-libraries-journal/article/abs/stuff-of-everyday-life-a-brief-introduction-to-the-history-and-definition-of-printed-ephemera/9DB2C34164B19D4C862818709AA79780.

- ↑ McAleer & MacKenzie 2015, p. 150.

- ↑ Young, Timothy G. (2003). "Evidence: Toward a Library Definition of Ephemera". RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 4 (1): 11–26. doi:10.5860/rbm.4.1.214. ISSN 2150-668X.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Altermatt, Rebecca; Hilton, Adrien (2012). "Hidden Collections within Hidden Collections: Providing Access to Printed Ephemera". The American Archivist 75 (1): 171–194. doi:10.17723/aarc.75.1.6538724k51441161. ISSN 0360-9081. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23290585.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Lambert, Julie Anne; Rickards, Maurice (2003), "Ephemera, printed", Oxford Art Online, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t026405, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t026405, retrieved 2021-11-28

- ↑ Jung, Sandro (2020). "Literary Ephemera: Understanding the Media of Literacy and Culture Formation". Eighteenth-Century Life 44 (2): 1–16. doi:10.1215/00982601-8218580. ISSN 1086-3192. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/758816.

- ↑ Cocks, Harry G.; Rubery, Matthew (2012). "Introduction". Media History 18 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1080/13688804.2011.634650. ISSN 1368-8804. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2011.634650.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Russell 2020, p. 3.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Harris, Michael (2010). "Printed Ephemera". in Suarez, Michael F.; Woudhuysen, H.R.. The Oxford companion to the book. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957014-0. OCLC 502389441. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198606536.001.0001/acref-9780198606536-e-0014?rskey=K7zf5P&result=3821.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Suarez & Turner 2010, p. 66–67.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 MacKenzie 1984, p. 21.

- ↑ Eliot & Rose 2019, pp. 635–636.

- ↑ De Mûelenaere, Gwendoline (2022). Early Modern Thesis Prints in the Southern Netherlands: An Iconological Analysis of the Relationships Between Art, Science and Power. Brill. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-90-04-44453-9. OCLC 1259587568. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1259587568.

- ↑ Suarez & Turner 2010, p. 74.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 McAleer & MacKenzie 2015, p. 145.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Osbaldestin, David Joseph (2020). "The Art of Ephemera: Typographic Innovations of Nineteenth-Century Midland Jobbing Printers". Midland History 45 (2): 208–221. doi:10.1080/0047729x.2020.1767975. ISSN 0047-729X. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0047729x.2020.1767975.

- ↑ McAleer & MacKenzie 2015, p. 146.

- ↑ Eliot & Rose 2019, p. 636.

- ↑ Murphy & O'Driscoll 2013, p. 199.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Quirk, Linda (2016). "Proliferating Ephemera in Print and Digital Media". ESC: English Studies in Canada 42 (3): 22–24. doi:10.1353/esc.2016.0027. ISSN 1913-4835. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/663384.

- ↑ The Multigraph Collective (2018). Interacting with Print: Elements of Reading in the Era of Print Saturation. University of Chicago Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780226469287.

- ↑ Linley, Margaret (2019). "The Mediated Mind: Affect, Ephemera, and Consumerism in the Nineteenth Century by Susan Zieger (review)". Victorian Studies 62 (1): 125–127. doi:10.2979/victorianstudies.62.1.09. ISSN 1527-2052. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/753358.

- ↑ Pettegree 2017, p. 79.

- ↑ Weaver 2010, p. 41–50.

- ↑ Zieger 2018, p. 16.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 55.4 55.5 Andrews, Martin J. (2006). "The stuff of everyday life: a brief introduction to the history and definition of printed ephemera" (in en). Art Libraries Journal 31 (4): 5–8. doi:10.1017/S030747220001467X. ISSN 0307-4722. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/art-libraries-journal/article/abs/stuff-of-everyday-life-a-brief-introduction-to-the-history-and-definition-of-printed-ephemera/9DB2C34164B19D4C862818709AA79780.

- ↑ Pettegree 2017, p. 81.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Suarez & Turner 2010, p. 68.

- ↑ Grisham, Leah (2019). "The Mediated Mind: Affect, Ephemera, and Consumerism in the Nineteenth Century by Susan Zieger (review)". Victorian Periodicals Review 52 (1): 210–212. doi:10.1353/vpr.2019.0011. ISSN 1712-526X. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/722860.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Stone 2005, p. 6.

- ↑ Newman, Ian; Russell, Gillian (2019). "Metropolitan Songs and Songsters: Ephemerality in the World City". Studies in Romanticism 58 (4): 429–449. doi:10.1353/srm.2019.0034. ISSN 2330-118X. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/747834.

- ↑ McAleer & MacKenzie 2015, p. 143.

- ↑ Holmes, Nina (2019). "Maternal subjects: representations of women in Irish government health ephemera, 1970s-1980s". The History of the Family 24 (4): 707–743. doi:10.1080/1081602X.2019.1610667. ISSN 1081-602X. https://doi.org/10.1080/1081602X.2019.1610667.

- ↑ Berger, J M; Aryaeinejad, Kateira; Looney, Seán (2020). "There and Back Again: How White Nationalist Ephemera Travels Between Online and Offline Spaces". The RUSI Journal 165 (1): 114–129. doi:10.1080/03071847.2020.1734322. ISSN 0307-1847. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2020.1734322.

- ↑ Craske, Matthew (1999). "Plan and Control: Design and the Competitive Spirit in Early and Mid-Eighteenth-Century England". Journal of Design History 12 (3): 187–216. doi:10.1093/jdh/12.3.187. ISSN 0952-4649. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1316282.

- ↑ Suarez & Turner 2010, p. 78.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Russell, Gillian (2015). ""Announcing each day the performances": Playbills, Ephemerality, and Romantic Period Media/Theater History". Studies in Romanticism 54 (2): 241–268. doi:10.1353/srm.2015.0024. ISSN 2330-118X. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/741580.

- ↑ Bellows 2020, p. 159–160.

- ↑ Teukolsky, Rachel (2020) (in en). Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 100, 357. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198859734.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-885973-4. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780198859734.001.0001/oso-9780198859734.

- ↑ Iskin & Salsbury 2019, p. 119.

- ↑ Zieger 2018, p. 14.

- ↑ Fraser, Alison (2019). "Mass Print, Clipping Bureaus, and the Pre-Digital Database: Reexamining Marianne Moore's Collage Poetics through the Archives". Journal of Modern Literature 43 (1): 19–33. doi:10.2979/jmodelite.43.1.02. ISSN 1529-1464. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/745755.

- ↑ Eliot & Rose 2019, pp. 472–473.

- ↑ Fyfe, Paul (2015). By Accident or Design: Writing the Victorian Metropolis. Oxford University Press. pp. 165. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198732334.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-873233-4. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198732334.001.0001/acprof-9780198732334.

- ↑ Hammond, Catherine (2016). "Escaping the digital black hole: e-ephemera at two Auckland art libraries". Art Libraries Journal 41 (2): 107–114. doi:10.1017/alj.2016.10. ISSN 0307-4722. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/alj.2016.10.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 Callaghan, Holly (2013). "Electronic ephemera: collection, storage and access in Tate Library". Art Libraries Journal 38 (1): 27–31. doi:10.1017/s0307472200017843. ISSN 0307-4722. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0307472200017843.

- ↑ Govil, Nitin (2022). "Keanu's late style: the ubiquitous art of short-form celebrity". Celebrity Studies 13 (2): 214–227. doi:10.1080/19392397.2022.2063402. ISSN 1939-2397. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2022.2063402.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Deutch, Samantha; McKay, Sally (2016). "The Future of Artist Files: Here Today, Gone Tomorrow". Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 35 (1): 27–42. doi:10.1086/685975. ISSN 0730-7187. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26557039.

- ↑ Slania, Heather (2013). "Online Art Ephemera: Web Archiving at the National Museum of Women in the Arts" (in en). Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 32 (1): 112–126. doi:10.1086/669993. ISSN 0730-7187. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/669993.

- ↑ Bardiot, Clarisse (2021). Performing Arts and Digital Humanities: From Traces to Data. 5. Wiley. pp. 26. ISBN 9781119855569.

- ↑ Lange, Alexandra (2015-03-24). "Instagram's Endangered Ephemera" (in en-US). The New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/instagrams-beautiful-ephemera. Retrieved 2022-05-21.

- ↑ Iskin & Salsbury 2019, p. 125.

- ↑ Wasserman 2020, p. 236.

- ↑ Russell, Edmund; Kane, Jennifer (2008). "The Missing Link : Assessing the Reliability of Internet Citations in History Journals". Technology and Culture 49 (2): 420–429. doi:10.1353/tech.0.0028. ISSN 0040-165X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40061522.

- ↑ Nelson, Amelia; Timmons, Traci E., eds (2021). The New Art Museum Library. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 51. ISBN 978-1538135709. https://books.google.com/books?id=8jUXEAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Wasserman 2020, p. 231.

- ↑ Slate, John H. (2001). "Not Fade Away". Collection Management 25 (4): 51–59. doi:10.1300/J105v25n04_06. ISSN 0146-2679. https://doi.org/10.1300/J105v25n04_06.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 Burant, Jim (1995). "Ephemera, Archives, and Another View of History" (in en). Archivaria 40: 189–198. ISSN 1923-6409. https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/12105.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Stone 2005, p. 13.

- ↑ Snyder, Terry (2014). "Spectacular Ephemera". Transformations: The Journal of Inclusive Scholarship and Pedagogy 24 (1–2): 101–109. ISSN 1052-5017. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/trajincschped.24.1-2.0101.

- ↑ Field 2019, p. 81.

- ↑ Zieger 2018, p. 2.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Salmon, Richard (2020). "Consuming Ephemera". Criticism 62 (1): 151–155. doi:10.13110/criticism.62.1.0151. ISSN 1536-0342. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/764107.

- ↑ MacKenzie 1984, p. 17.

- ↑ Doster, Adam (2016). "Saving Digital Ephemera". American Libraries 47 (1/2): 18. ISSN 0002-9769. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24604193.

- ↑ Smith, Kai Alexis (2016). "Digitizing Ephemera Reloaded: A Digitization Plan for an Art Museum Library". Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America 35 (2): 329–338. doi:10.1086/688732. ISSN 0730-7187. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/688732.

- ↑ Haug, Mary-Elise (1995). "The Life Cycle of Printed Ephemera: A Case Study of the Maxine Waldron and Thelma Mendsen Collections". Winterthur Portfolio 30 (1): 59–72. doi:10.1086/wp.30.1.4618482. ISSN 0084-0416. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4618482.

- ↑ Bashford, Christina (2008). "Writing (British) Concert History: The Blessing and Curse of Ephemera". Notes 64 (3): 458–473. doi:10.1353/not.2008.0023. ISSN 1534-150X. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/232019.

- ↑ Giannachi, Gabriella (2016) (in en). Archive Everything: Mapping the Everyday. The MIT Press. pp. 76. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262035293.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-262-03529-3. http://mitpress.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.7551/mitpress/9780262035293.001.0001/upso-9780262035293.

- ↑ Weaver 2010, p. 135, 188.

- ↑ Mussell, James (2012). "The Passing of Print". Media History 18 (1): 77–92. doi:10.1080/13688804.2011.637666. ISSN 1368-8804. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2011.637666.

- ↑ Wasserman 2020, p. 230.

- ↑ Tschabrun, Susan (2003). "Off the Wall and into a Drawer: Managing a Research Collection of Political Posters". The American Archivist 66 (2): 303–324. doi:10.17723/aarc.66.2.x482536031441177. ISSN 0360-9081.

- ↑ Raine, Henry (2017). "From Here to Ephemerality: Fugitive Sources in Libraries, Archives, and Museums: The 48th Annual RBMS Preconference" (in en-US). RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 9 (1): 14–17. doi:10.5860/rbm.9.1.293. https://rbm.acrl.org/index.php/rbm/article/view/293.

- ↑ Randall, David (2004). "Recent Studies in Print Culture: News, Propaganda, and Ephemera". Huntington Library Quarterly 67 (3): 457–472. doi:10.1525/hlq.2004.67.3.457. ISSN 0018-7895.

- ↑ Vareschi, Mark; Burkert, Mattie (2016). "Archives, Numbers, Meaning: The Eighteenth-Century Playbill at Scale". Theatre Journal 68 (4): 597–613. doi:10.1353/tj.2016.0108. ISSN 1086-332X. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/645398.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 Sèbe, Berny; Stanard, Matthew G. (2020). Decolonising Europe?: Popular Responses to the End of Empire. Routledge. pp. 201. doi:10.4324/9780429029363. ISBN 9780429029363. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9780429029363/decolonising-europe-berny-s%C3%A8be-matthew-stanard.

- ↑ Iskin & Salsbury 2019, p. 118.

- ↑ Hadley, Nancy (2001). "Access and Description of Visual Ephemera". Collection Management 25 (4): 39–50. doi:10.1300/j105v25n04_05. ISSN 0146-2679. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/j105v25n04_05.

- ↑ Lambert, Julie Anne (2017). "Immortalizing the Mayfly: Permanent Ephemera: An Illusion or a (Virtual) Reality?". RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 9 (1): 142–156. doi:10.5860/rbm.9.1.304. https://rbm.acrl.org/index.php/rbm/article/view/304.

- ↑ Zieger 2018, p. 22.

- ↑ Lippert, Amy DeFalco (2018) (in en). Consuming Identities. Oxford University Press. pp. 319. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190268978.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-026897-8. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780190268978.001.0001/oso-9780190268978.

- Bibliography

- Bellows, Amanda Brickell (2020) (in en). American Slavery and Russian Serfdom in the Post-Emancipation Imagination. University of North Carolina Press. doi:10.5149/northcarolina/9781469655543.001.0001. ISBN 978-1-4696-5554-3. https://northcarolina.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.5149/northcarolina/9781469655543.001.0001/upso-9781469655543.

- Blum, Hester (2019). The News at the Ends of the Earth: The Print Culture of Polar Exploration. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-0448-6. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/65200.

- Buday, György. (1971). The History of the Christmas Card. Salisbury Square.

- Eliot, Simon, ed (2019). A Companion to the History of the Book (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-01821-6. OCLC 1099543594. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1099543594.

- Field, Hannah (2019). Playing with the Book: Victorian Movable Picture Books and the Child Reader. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-4529-5958-0. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/66674.

- Iskin, Ruth E.; Salsbury, Britany, eds (2019) (in en). Collecting Prints, Posters, and Ephemera. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/collecting-prints-posters-and-ephemera-9781501338496/. Retrieved 2021-12-19.

- McAleer, John, ed (2015). Exhibiting the Empire: Cultures of Display and the British Empire. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-9109-4.

- MacKenzie, John (1984). Propaganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880-1960. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-1499-9. OCLC 10208219. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/10208219.

- Murphy, Kevin; O'Driscoll, Sally, eds (2013). Studies in Ephemera : Text and Image in Eighteenth-Century Print. Bucknell University Press. ISBN 978-1-61148-494-6. OCLC 812254905. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/812254905.

- Pettegree, Andrew, ed (2017). Broadsheets: Single-sheet Publishing in the First Age of Print. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-34030-5. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctv2gjwnfd.

- Russell, Gillian (2020). The Ephemeral Eighteenth Century: Print, Sociability, and the Cultures of Collecting. Cambridge Studies in Romanticism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-48758-0. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/ephemeral-eighteenth-century/4F9B8D61D476ED883A5B739C720BBD4F.

- Stone, Richard (2005). Fragments of the Everyday: A Book of Australian Ephemera. National Library of Australia. ISBN 978-0-642-27601-8. https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/3413498.

- Suarez, Michael F. SJ; Turner, Michael L., eds (2010). The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain. 5. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/chol9780521810173. ISBN 9781139056069. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/the-cambridge-history-of-the-book-in-britain/DAF5B69ABC2F7FE4D37094EC03FEC96E.

- Wasserman, Sarah (2020). The Death of Things: Ephemera and the American Novel. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-4529-6414-0. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/78266.

- Weaver, William Woys (2010). Culinary Ephemera : an Illustrated History. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-94706-1. OCLC 794663706. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/794663706.

- Zieger, Susan (2018). The Mediated Mind: Affect, Ephemera, and Consumerism in the Nineteenth Century. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-7985-2. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/59089.

Further reading

- Printed Ephemera: The Changing Uses of Type and Letterforms in English and American Printing, John Lewis, Ipswich, Suffolk, Eng.: W. S. Cowell, 1962

- The Encyclopedia of Ephemera: A Guide to the Fragmentary Documents of Everyday Life for the Collector, Curator, and Historian by Maurice Rickards et alia. London: The British Library; New York: Routledge, 2000.

- Fragments of the Everyday: A Book of Australian Ephemera by Richard Stone (2005, ISBN 0-642-27601-3)

- Twyman, Michael (August 2002). "Ephemera: whose responsibility are they?". Library and Information Update 1 (5): 54–55. ISSN 1476-7171.

External links

- Ephemera Society of Australia

- The Ephemera Society

- Ephemera Society of America

- Printed Ephemera in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress

- Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives – Ephemera Collection

- National Library of Australia – Ephemera Collection

- GG Archives – Ephemera Collection

- British Library – Evanian Collection of Ephemera

- State Library of Victoria – Ephemera

- State Library of Western Australia – Ephemera

- The John Grossman Collection of Antique Images

- New Zealand Ephemera Society website

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France – Ephemera

- ephemerastudies.org at Louisiana Tech University

- Sheaff, Dick. "Sheaff: Ephemera". Ephemera. http://www.sheaff-ephemera.com/.

- Collection of digitized ephemera at Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Biblioteca Nacional de España

- Ephemerajournal. theory & politics of organization

|