Biology:Hemimysis anomala

| Hemimysis anomala | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Superorder: | Peracarida |

| Order: | Mysida |

| Family: | Mysidae |

| Subfamily: | Mysinae |

| Genus: | Hemimysis |

| Species: | H. anomala

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hemimysis anomala G. O. Sars, 1907

| |

The bloody-red mysid, Hemimysis anomala, is a shrimp-like crustacean in the Mysida order, native to the Ponto-Caspian region, which has been spreading across Europe since the 1950s.[1] In 2006, it was discovered to have invaded the North American Great Lakes.[2]

Distribution

The species is native to freshwater margins of the Black Sea, the Azov Sea and the eastern Caspian Sea. It has historically occurred in the lower reaches of the Don, Danube, Dnieper and Dniester rivers. In Europe, it has recently spread north west, reaching the Baltic Sea in 1992 and the United Kingdom in 2004.[2] The mysid's spread has been facilitated via its deliberate introduction into reservoirs on the Volga and Dnieper rivers in the 1950s and 1960s to serve as fish food.[3] Despite its spread throughout Europe, it is considered to be endangered in some parts of its indigenous range (Ukraine ).

The species has entered the Great Lakes via the ballast water exchange; it was reported for the first time in 2006 from two disjunct regions: southeastern Lake Ontario at Nine Mile Point near Oswego, New York in May 2006, and from a channel connecting Muskegon Lake to Lake Michigan in November 2006.[1] Specimens resembling H. anomala have also been found in the stomach contents of a white perch collected near Port Dover, Lake Erie in August 2006. The species was discovered in the Saint Lawrence River in July 2008; it is now found in all the major Great Lakes waterbodies, except for Lake Superior.[4]

Anatomy and morphology

thumb|left|Telsons of H. anomala and M. diluviana. Mature individuals reach 6–13 millimetres (0.24–0.51 in) in length; females are slightly larger than males. The species can be ivory-yellow in colour or translucent, but exhibits pigmented red chromatophores in the carapace and telson.[1] The intensity of colouration, believed to be associated with the species' crepuscular behaviour,[5] varies with contraction or expansion of the chromatophores in response to light and temperature conditions; in shaded areas, individuals tend to have a deeper red colour. Juveniles are more translucent than adults. Preserved individuals lose their colour, becoming opaque. H. anomala is distinguishable from other mysid species including the Great Lakes' native opossum shrimp Mysis diluviana by its truncated telson with a long spine at both corners; by contrast, M. diluviana has a forked telson.[2]

Habitat

The bloody-red mysid favours hard bottom surfaces, including rocks and shells and avoids soft bottoms and areas of dense vegetation or high siltation. In its native range, the species is found in water depths ranging from 0.5 to 50 metres (1.6 to 164.0 ft), although they generally inhabit depths of 6–10 m (20–33 ft). The species is normally found in lentic waters, although it has successfully established in European rivers; it has also been found along rocky, wave-exposed shorelines. It tolerates salinity concentrations of 0–19 ppt and prefers water temperatures of 9–20 °C (48–68 °F). Populations may survive temperatures of 0 °C (32 °F) over winter, but not without substantial mortality.

Food

H. anomala is an opportunistic omnivore that feeds primarily on zooplankton, particularly cladocerans, but also consumes detritus, phytoplankton (particularly green algae and diatoms), and insect larvae, and is occasionally cannibalistic.[1] Younger individuals feed mainly on phytoplankton. The proportion of zooplankton consumed in the mysid's diet increases with its body size. A bloody-red mysid feeds using its thoracic limbs, either by capturing prey with its endopods or by removing food particles from its body that are filtered from incoming currents by its exopods.

Behaviour

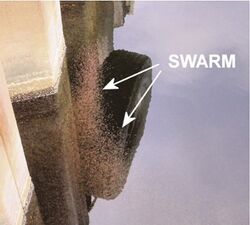

Individuals remain near profundal sediments during the day, migrate in swarms to the upper water column at twilight, then return to the profundal zone at dawn.[1] Only males tend to undergo these migrations. Juvenile H. anomala often inhabit different positions (usually higher) in the water column than adults, possibly to avoid cannibalism. Being more transparent, juveniles may be less at risk of fish predation than adults. The adults are fast swimmers, moving at several centimetres per second when alarmed. Bloody-red mysids generally avoid areas where other mysid species are found. Their tendency to aggregate creates locally dense swarms up to several square meters in area. During daylight hours, especially in late summer, these reddish swarms can be observed in the shadows of piers, boats, or breakwalls; at night, the swarms disperse.[2] The species is also reported to spend daylight hours hiding in rocky crevices and boulder cavities.

Life history

H. anomala breeds from April to September / October. Sexual maturity occurs in 45 days; life span is about 9 months.[2] Females become ovigerous at 8–9 °C (46–48 °F) and produce 2 to 4 broods per year. Brood size is correlated with female length and ranges from 6 to 70 embryos per individual.

Impact as an invasive species

Given the species' very recent introduction into the Great Lakes, its impact is yet to be established. It is not expected to compete with the native M. relicta, as it prefers the cold water environments below the lakes' thermocline, while H. anomala is best adapted to warmer conditions.[3] In Europe, the species has been observed to disrupt food webs and alter nutrient and contaminant cycles of environments into which it was introduced. The mysid has been associated with reduction of zooplankton biomass and biodiversity, while having an opposite effect on phytoplankton. Pelagic fish in many ecosystems have been negatively affected by the species' introduction; however, salmonids and benthic fish seem to benefit from the new food source. The species' routine vertical migration through the water column results in continuous cycling of pollutants, such as heavy metals, that would otherwise be confined to the benthic zone.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Hemimysis anomala Factsheet". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 17, 2007. Archived from the original on May 22, 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070522002412/http://www.glerl.noaa.gov/hemimysis/hemi_sci_factsheet.html. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Great Lakes New Invader: Bloody Red Shrimp (Hemimysis anomala)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.glerl.noaa.gov/res/Programs/glansis/hemi_brochure.html. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Anthony Riccardi (March 2007). "Forecasting the impacts of Hemimysis anomala: the newest invader discovered in the Great Lakes" (PDF). The National Aquatic Nuisance Species Clearinghouse 18 (1): 1, 4–7. http://www.glerl.noaa.gov/pubs/fulltext/2007/20070006.pdf.

- ↑ Åsa M. Kestrup; Anthony Ricciardi (December 19, 2008). "Occurrence of the Ponto-Caspian mysid shrimp Hemimysis anomala (Crustacea, Mysida) in the St. Lawrence River" (PDF). Aquatic Invasions 3 (4): 461–464. doi:10.3391/ai.2008.3.4.17. http://www.aquaticinvasions.net/2008/AI_2008_3_4_Kestrup_Ricciardi.pdf.

- ↑ Steven A. Pothoven; Igor A. Grigorovich; Gary L. Fahnenstiel; Mary D. Balcer (2007). "Introduction of the Ponto-Caspian Bloody-red Mysid Hemimysis anomala into the Lake Michigan Basin" (PDF). Journal of Great Lakes Research 33: 285–292. doi:10.3394/0380-1330(2007)33[285:iotpbm2.0.co;2]. http://www.glerl.noaa.gov/pubs/fulltext/2007/20070007.pdf.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q1758554 entry

|