Biology:Invasin

| inverse autotransporter invasin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | inv | ||||||

| Entrez | 77327691 | ||||||

| PDB | 1CWV (ECOD) | ||||||

| RefSeq (Prot) | WP_263696614.1 | ||||||

| UniProt | P19196 | ||||||

| Other data | |||||||

| Chromosome | Genomic: 1.75 - 1.75 Mb | ||||||

| |||||||

Invasins are a class of bacterial proteins associated with the penetration of pathogens into host cells.[1] Invasins play a role in promoting entry during the initial stage of infection.[2][3]

In 2007, Als3 was identified as a fungal invasion allowing Candida albicans to infect host cells.[4]

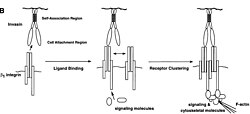

Invasin is a small membrane bound protein that enables the infiltration of cultured mammalian cells by enteric bacteria. The cellular entry of invasin is facilitated through the binding of multiple β1 chain integrins.[5] The interplay between invasin and β1 integrins initiates a reconfiguration of the cytoskeleton in the target cell, culminating in the creation of a groove and the internalization of bacteria through endosomes by the cell. Invasin is expressed inYersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis because of its outermembrane being chromosomally encoded.[6] Invasin demonstrates a significantly enhanced binding affinity to β1 integrins compared to the natural ligands of the receptor. More precisely, it forms a robust attachment to the α5β1 integrin, typically employed by fibronectin, exhibiting roughly 100 times greater strength. This heightened binding capability arises from structural disparities between the two proteins. The extracellular region of invasin adopts a rod-like configuration, with dimensions measuring approximately 180 Å by 30 Å by 30 Å.[7]

Examples

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, a Gram-negative bacterium and zoonotic pathogen, is accountable for various diseases, spanning mild diarrhea, enterocolitis, lymphatic adenitis, to enduring local inflammation. The invasin D molecule of Y. pseudotuberculosis (InvD) is classified under the invasin (InvA)-type autotransporter proteins, yet its structure and function remain undiscovered.[8] This bacterium induces a food-borne infection marked by a self-limiting mesenteric lymphadenitis that imitates symptoms of appendicitis.[9]

Yersinia enterocolitica

Yersinia enterocolitica is a gram-negative bacillus-shaped bacterium that gives rise to yersiniosis, a zoonotic disease. This infection presents as acute diarrhea, mesenteric adenitis, terminal ileitis, and pseudoappendicitis, occasionally progressing to sepsis. In certain regions, yersinia infections have surpassed shigella and salmonella species as the leading cause of bacterial gastroenteritis. While most cases occur sporadically, notable outbreaks are not uncommon. Humans typically contract yersinia through the consumption of contaminated food or blood transfusions. Y. enterocolitica has been detected in various animals, with pigs serving as the primary reservoir. The pathogen can disseminate within pig herds, contaminating pork products like neck trimmings, tongue, and tonsils, potentially spreading to other meat cuts during the slaughtering process.[10]

Structure

The extracellular region of invasin, composed of the COOH-terminal 497 residues, can be expressed as a soluble protein (Inv497). This protein binds to integrins and facilitates uptake when attached to bacteria or beads. The shortest invasin fragment capable of integrin binding consists of the COOH-terminal 192 amino acids. Notably, this fragment lacks homology with the integrin-binding domains of fibronectin, specifically the fibronectin type III repeats 9 and 10 (Fn-III 9–10). However, invasin and fibronectin share binding sites on α3β1 and α5β1 integrins, with the integrin-binding region of invasin showing no significant sequence identity with the corresponding regions of intimins.[11]

Invasin residues crucial for integrin binding are at positions 903 to 913, constituting helix 1 and the subsequent loop in D5. The disulfide bond between Cys906 and Cys982, a conserved feature in all CTLDs, is essential for integrin binding, likely due to its role in ensuring proper folding. Despite the absence of an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence, a critical element in Fn-III 10 for interacting with integrins, invasin relies on Asp911 in Inv497 D5 for integrin binding. Similar to the aspartate in the Fn-III RGD sequence, Asp911 is situated within a loop. Another invasin region, approximately 100 amino acids from Asp911, contains additional residues implicated in integrin binding, including Asp811. This particular invasin segment bears a resemblance to the fibronectin synergy region in Fn-III 9, crucial for optimal α5β1 integrin-dependent cell spreading. Invasin Asp811, positioned in D4 between strands A" and A‴, shares the same surface as Asp911, separated by a distance of 32 Å. The distance between Fn-III 10 Asp1495 in the RGD sequence and Fn-III 9 Asp1373 in the synergy region is also 32 Å, although the side-chain orientation of Asp1373 differs from that of Asp811 in invasin. Within the Fn-III synergy region, the residue for integrin binding is Arg1379. Invasin and host proteins have integrin-binding features that are fairly similar.[11]

The transmembrane segments of outer membrane proteins with known structures exhibit a β-barrel architecture, exemplified by porins. Assuming that the membrane-associated section of invasin also forms a β-barrel, with the cell-binding region extending approximately 180 Å from the bacterial surface, it is positioned to engage host cell integrins. The parallels between invasin and fibronectin indicate the convergent evolution of shared integrin-binding characteristics. Unlike the fibronectin-binding surface, the integrin-binding region of the invasin lacks a cleft; which can result in invasin binding integrins with a larger interface.[11]

Mechanism of action

Entry into M-cells occurs by utilizing a small membrane-bound protein known as invasin. This protein exhibits a strong attraction to the b1 superfamily of integrins present on the outer surface of various mammalian cells. Interestingly, these integrins do not play a role in particle ingestion; instead, they are involved in processes like adhesion to the extracellular matrix, interactions with cell surfaces, migration, and differentiation. The natural partners of these receptors include fibronectin, collagen, vitronectin, and laminin, although invasin forms a stronger bond with them. Notably, invasin selectively binds to specific members within the β1 integrins family. Invasin will bind exclusively to a subset of the b1 subfamily of integrins, specifically α3β1, α4β1, α5β1, α6β1, and αVβ1.[7]

Potential applications

The invasin protein has a particular interest in future use in oral gene discovery. Delivering genes non-virally through oral administration holds great promise for enhancing the efficacy of DNA vaccination and gene therapy applications. Unlike traditional parenteral routes, the oral approach is non-invasive, promoting increased patient compliance and simplified dosing. Furthermore, oral administration enables the production of therapeutic genes locally and systemically. In the case of DNA vaccination, it fosters the development of both mucosal and systemic immunity.[13]

References

- ↑ "Invasin". Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. Wolters Kluwer Health. http://www.medilexicon.com/dictionary/45483.

- ↑ "Identification of invasin: a protein that allows enteric bacteria to penetrate cultured mammalian cells". Cell 50 (5): 769–778. August 1987. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90335-7. PMID 3304658.

- ↑ "Yersinia enterocolitica invasin: a primary role in the initiation of infection". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 90 (14): 6473–6477. July 1993. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.14.6473. PMID 8341658. Bibcode: 1993PNAS...90.6473P.

- ↑ "Als3 is a Candida albicans invasin that binds to cadherins and induces endocytosis by host cells". PLOS Biology 5 (3): e64. March 2007. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050064. PMID 17311474.

- ↑ "Invasin: Yersinia enterocolitica". UniProt. https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/P19196/entry.

- ↑ "Yersinia". Principles of Bacterial Pathogenesis. 2001. pp. 227–264. doi:10.1016/B978-012304220-0/50007-8. ISBN 978-0-12-304220-0. "Invasin (Inv) is a chromosomally encoded outer membrane protein that is expressed in both Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis."

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Bacterial invasin: structure, function, and implication for targeted oral gene delivery". Current Drug Delivery 3 (1): 47–53. January 2006. doi:10.2174/156720106775197475. PMID 16472093.

- ↑ "The invasin D protein from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis selectively binds the Fab region of host antibodies and affects colonization of the intestine". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 293 (22): 8672–8690. June 2018. doi:10.1074/jbc.ra117.001068. PMID 29535184.

- ↑ "Yersinia Pseudotuberculosis". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430717/. Retrieved 2023-11-28.

- ↑ "Yersinia Enterocolitica". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499837/. Retrieved 2023-11-28.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 PDB: 1CWV; "Crystal structure of invasin: a bacterial integrin-binding protein". Science (New York, N.Y.) 286 (5438): 291–295. October 1999. doi:10.1126/science.286.5438.291. PMID 10514372.

- ↑ "A region of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis invasin protein enhances integrin-mediated uptake into mammalian cells and promotes self-association". The EMBO Journal 18 (5): 1199–1213. March 1999. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.5.1199. PMID 10064587.

- ↑ "Oral Non-Viral Gene Delivery for Applications in DNA Vaccination and Gene Therapy". Current Opinion in Biomedical Engineering 7: 51–57. September 2018. doi:10.1016/j.cobme.2018.09.003. PMID 31011691.

External links

|