Biology:Kibi dango (millet dumpling)

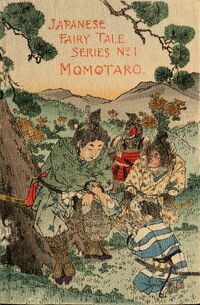

Kibi dango (黍団子, きびだんご, "millet dumpling") is Japanese dumpling made from the meal or flour of the kibi (proso millet) grain.[1][2] The treat was used by folktale-hero Momotarō (the Peach Boy) to recruit his three beastly retainers, in the commonly known version of the tale.[3]

In modern times, this millet dumpling has been confused with the identically-sounding confection Kibi dango[4] named after Kibi Province (now Okayama Prefecture), even though the latter hardly uses any millet at all.[5] The confectioners continue to market their product by association with the hero Momotarō,[4] and more widely, Okayama residents have engaged in a concerted effort to claim the hero as native to their province.[6] In this context, the millet dumpling's historical association with the Kibi Province has undergone close scrutiny. In particular, Kibitsu Shrine of the region has had ongoing association with serving food by the name kibi dango.

Conventionally, kibi dango or kibi mochi uses the sticky variety proso millet known as mochi kibi, rather than the regular (amylose-rich) millet used for creating sweets.[7]

History

Use of the term kibi dango in the sense of "millet dumpling" occurs at least as early as the Yamashinake raiki (『山科家礼記』, "Diary of the Yamashina Family"), in an entry dated 1488 (Chōkyō 2, 3rd month, 19th day) which mentions "kibi dango".[8][9] The Japanese-Portuguese dictionary Nippo Jisho (1603–04) also listed "qibidango", which it defined as "millet dumpling".[lower-alpha 1][1][10]

There had been similar foods in earlier times, though not specifically called kibi dango. Writer Akatsuki Kanenari in his 1862 essay collection observed that such foods, made out of millet meals or other ground grains undergoing a process of steaming and pounding, and recognizable as dango to his contemporaries, were once called bei (餅, the same character as mochi) in the olden days.[11]

Kibitsu Shrine

The Kibitsu Shrine of the former Kibi Province has an early connection to the millet dumpling, due to the easy pun on the geographic name "Kibi" sounding the same as kibi 'millet'. The pun is attested in one waka poem and one haiku dating to the early 17th century, brought to attention by poet and scholar Shida Giyū in a treatise written in 1941.[12][13]

The first example, a satirical kyōka composed at the shrine by the feudal lord Hosokawa Yūsai (d. 1610) reads "Since priestess/pestle (kine) is traditional to the gods, I would fain see straightaway pounded into dumplings (the millet of) the Millet Shrine/Kibitsu Shrine (where I am at)."[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] The kine (杵, 'pestle or mallet-pestle') is a tool used in conjunction with a wooden mortar (usu),[14] and it is implicit in the poem that the process required these tools to pound the grain into kibi-dango dumplings.[lower-alpha 4]. And it must have been something the shrine served to visitors on some occasions, one source venturing as far as to say that "it was already being sold at Kibitsu Shrine at the time.[15]

A haiku in similar vein, of somewhat later date and also at the same shrine according to Shida, was composed by an obscure poet named Nobumitsu (信充) of Bitchū Province. The haiku reads "Oh, mochi-like snow, Japan's number one Kibi dango",[lower-alpha 5] The occurrence here of the line "Japan's number one kibi dango" which recurs as a stock phrase in the Momotarō story[16] constituted "immovable" proof of an early Momotarō connection in Shida's estimation, but it was based on the underlying conviction that this phrase was ever-present since the earliest inception of the Momotarō legend. That premise was later compromised by Koike Tōgorō, who after examining Edo-period texts of Momotarō concluded that "Japan's number one" or even "millet dumpling" had not appeared in the tale until decades after this haiku.[17][lower-alpha 6]

In later years, more elaborate legends were promoted connecting the shrine, or rather its resident deity Kibitsuhiko-no-mikoto to the kibi dango. The founder of the Kōeido confection business authored a travel guide in 1895, in which he claimed that Kibitsuhiko rolled with his own hand some kibi dango to give to Emperor Jimmu who stopped at Takayama Palace in Okayama,[18] but that anecdote was purely anachronistic.[lower-alpha 7] Later, an amateur historian wrote a 1930 book proposing that the legend of Kibitsuhiko's ogre-slaying was the source of the "Peach Boy" or Momotarō folktale,[19] leading to fervent local efforts to localize the hero Momotarō to Kibi Province (Okayama Prefecture).[20]

Momotarō legend

In the widely familiar version of Momotarō, the hero spares his traveling rations of "kibi dango" to a dog, a pheasant, and a monkey and thereby gains their allegiance. However the scholar Koike compared the various kusazōshi texts and discovered that early written texts of the Momotarō legend failed to call the rations "kibi dango". Versions from the Genroku era (1688–1704) has tō dango (とう団子, 十団子, "ten-count dumplings"), and other tales antedating "kibi dango" have daibutsu mochi (大仏餅) "Great Buddha cake" or ikuyo mochi (いくよ餅)[lower-alpha 8] instead. Moreover, the "Japan's number one" brag was unattached to Momotarō's kibi dango until around the Genbun era (1736) as far as Koike could fathom.[17][lower-alpha 6]

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Spelled "kibidango" (defined as "boulettes de millet") in the French translation of this Japanese-Portuguese dictionary.[2]

- ↑ Kami wa kine ga narawashi nareba mazu tsukite dango ni shitaki Kibitsu Miya kana (神はきねがならはしなれば先づ搗きて団子にしたき吉備津宮かな). A selection from the Kokin ikyokushū (『古今夷曲集』), published 1666.

- ↑ There are double entendres played here on the word kine ('priestess' or 'pestle') and the name Kibitsu, which could be construed as kibi-tsu or 'millet's'.

- ↑ Conceivably the raw grain could have been pounded into meal then formed into cakes, or the steamed millet mass could have been pounded into shape like how mochi is made, but such details are not clarifiable from the poem.

- ↑ Mochiyuki ya, Nihon ichi no Kibi dango (餅雪や日本一の吉備だんご), from the Konronshū (崑山集) of 1651.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Koike was actually refuting Shimazu Hisamoto, who likewise considered the "Japan's number one" phrase proof positive of the antiquity of the Momotarō tale.

- ↑ Prince Kibitsuhiko in life was an 8th generation descendant and unborn during the time of Jimmu.

- ↑ Named after Ikuyo, a woman of the pleasure quarters, according to one explanation.

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Shinmura ed. (1991), Kojien dictionary: "きび‐だんご【黍団子】キビの実の粉で製した団子〈日葡〉", lit. "kibi dango: dango made from pulverized kibi grain (from Nippo Jisho)"

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Pagés, Léon (1868), Dictionnaire Japonais-Français: Traduit du Dictionnaire Japonais-Portug. composé par les missionnaire de la compagnie de Jésus et imprimé en 1603, à Nangasaki, Benj. Duprat, p. 483, https://books.google.com/books?id=2-RGAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA483: "Kibidango キビダンゴ boulettes de millet"

- ↑ Antoni, Klaus (1991). "Momotaro and the Spirit of Japan". Asian Folklore Studies 50: 163. https://books.google.com/books?id=NnfhAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kahara (2004), p. 43

- ↑ Kahara (2004), p. 41

- ↑ Kahara (2004)

- ↑ Nishikawa, Goro; Ohwi, Jisaburo (1965), "kibi [きび]", Heibonsha's world encyclopedia, 5, p. 694

- ↑ Iikura, Harutake, ed. (2012), Yamashina raiki dai 4, 22, Zokugunshorui-ju kanseikai, https://books.google.com/books?id=jaPTAAAAMAAJ

- ↑ Nihon Kokugo Daijiten, entry under "kibi-dango [きび‐だんご]"

- ↑ Hayashi, Fumiko 林文子 (2008), "Nippo jisho ga kataru shoku no fūkei (1)" (in ja), Essays and studies. Science reports of Tokyo Woman's Christian University 58 (2): 130, http://id.nii.ac.jp/1632/00025245/

- ↑ Akatsuki, Kanenari (2007), "雲錦随筆 (Unkin zuihitsu)" (in ja), Nihon zuihitsu taisei, Yoshikawa Kobunkan, p. 133, https://books.google.com/books?id=Jl_0AAAAMAAJ

- ↑ Shida (1941), pp. 312–313

- ↑ Fujii, Shun 藤井駿 (1980) (in ja), Kibi chihōshi no kenkyū, Sanyōshinbunsha, pp. 91–92

- ↑ Verschuer, Charlotte von (2016). Rice, Agriculture, and the Food Supply in Premodern Japan. Routledge. pp. 86, 91 (fig. 1.4). ISBN 978-1-317-50450-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=j2aaCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA86.

- ↑ Tarora, Yūko 太郎良裕子 (2001) (in ja), Okayama no wagashi, 岡山文庫, 209, Nihon Bunkyo Shuppan, p. 33, https://books.google.com/books?id=Gv2xAAAAIAAJ

- ↑

Polen, James Scott (2008). Continuity and Change of Momotarō (PDF) (MA Art thesis). University of Pittsburgh. p.39 (endnote 40 to p.30).

Some versions of the folktale explain that [the millet dumplings] were nihon'ichi (Japan's best)

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Koike (1967), pp. 21, 30–31

- ↑ Takeda, Asajirō 武田淺次郎 (1895), Sanyō meisho ki, Okayama: Nihon no Densetsu to Dōwa, pp. 1–5, 45, http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1084841

- ↑ Kahara (2004), p. 44: Nanba Kinnosuke's Momotarō no shijitsu (1930)

- ↑ Kahara (2004), p. 41.

References

- Kahara, Nahoko (2004). "From Folktale Hero to Local Symbol: The Transformation of Momotaro (the Peach Boy) in the Creation of a Local Culture". Waseda Journal of Asian Studies 25: 35–. https://books.google.com/books?id=ExAOAQAAMAAJ.

- Henry, David A. (2009). Momotarō, or the Peach Boy: Japan's Best-Loved Folktale as National Allegory (PDF) (PhD thesis). 25. University of Michigan. pp. 35–.

- Koike, Tōgorō (1967). "A Study of 'Momotaro' : Based on Old Literature". Journal of the Faculty of Letters, Risshō University (26): 3–39 (pp. 21, 30–31). ISSN 0485-215X. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110000477022.

- Shida, Gishū (1941), "Kahen 2 Momotarō gairon [下篇 2 桃太郞槪論 "], Nihon no densetsu to dōwa, Daito Shuppansha, pp. 303–315, http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1453466

|