Biology:Leucospermum oleifolium

| Leucospermum oleifolium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Leucospermum |

| Species: | L. oleifolium

|

| Binomial name | |

| Leucospermum oleifolium | |

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Leucospermum oleifolium is an erect shrub of about 1 m (3.3 ft) high and 1½ m (5 ft) across that is assigned to the family Proteaceae. It has spreading branches, densely set with initially felty, entire, oval, olive-colored leaves of about 3½ cm (1½ in) long and 1½ cm (0.6 in) wide, with a bony tip that sometimes has two to five blunt teeth, with a blunt base and conspicuous veins. The flowers and their long thread-like styles are initially sulfur yellow, but soon become orange and finally turn brilliant crimson. The flower heads are about 4 cm (1.6 in) in diameter, crowded at the tip of the branches with a maximum of five that start flowering in turn. This provides for a colour spectacle from August till December. It is called by various names in South Africa such as Overberg pincushion, flame pincushion, mix pincushion and tuft pincushion.[3][4] It naturally occurs in fynbos in the Western Cape province of South Africa.[2]

Description

Leucospermum oleifolium is an erect, usually compact and rigid shrub of about 1 m (3.3 ft) high and 1½ m (5 ft) across with a single stem at its base, and branches bending upwards. Stems that are ready to flower are 3–6 mm (0.12–0.24 in) in diameter, softly hairy when young, but later losing these fine hairs. The leaves have no stalks or bracts at their base, are initially softly hairy but losing its indumentum when aging, 4–6 cm (1.6–2.4 in) long and 8–25 mm (0.31–0.98 in) wide, with an entire, sometimes wavy margin, and a bony tip that may have one to five blunt teeth.[2]

The cup-shaped flower heads are each 2½–4 cm (1.0–1.6 in) in diameter, almost without a peduncle, with two to five crowded at the end of the branches, occasionally on its own. The floral base is flat and 12 mm (0.47 in) in diameter. It is covered below by felty to hairless, papery, egg-shaped, long pointed, overlapping involucral bracts of 9–36 mm (0.35–1.42 in) long and 5–7 mm (0.20–0.28 in) wide, sometimes with a tuft of long hairs at its tip. The papery bracts at the base of the individual flowers are very narrowly lance-shaped, 1–3 cm (0.39–1.18 in) long, wooly near the base and sofly hairy towards the tip. The individual flower bud is a straight tube of about 2 cm (0.79 in) long, slightly transparante, initially whitish-transparent to pale yellowish green, yellow when opening, quickly becoming orange and turning bright crimson with age. When the flower opens, a cylindrical, hairless tube of 8 mm (0.31 in) remains that widens towards the top, and four thread-shaped lobes that are strongly curled on itself. The styles are initially strongly arched like a swan's neck, but straighten and grow quickly to a thread of 2½–3 cm (1–1¼ in) long, at first pale yellow but turning crimson when fully developed. The pollen-presenter, a slight thickening at the tip of the style (comparable with the "head" of the pin), is cylindrical, thread-like, only at its base slightly thicker than the style, 1 mm (0.039 in) long, the stigma a groove across the tip of the pollen-presenter. At the base of the ovary are for blunt thread-like opaque scales of about 2 mm (0.079 in) long.[2] The fruit is ellipsoid in shape, 7½ mm (0.3 in) long, the surface thinly covered with a fine powder.[5] The species flowers between August and January, peaking in September and October. Initially the flowers are bright yellow, but soon turn orange to end in a brilliant crimson, and they may remain vibrant for almost two months.[3]

The subtribe Proteinae, to which the genus Leucospermum has been assigned, consistently has a basic chromosome number of twelve (2n=24).[6]

Taxonomy

This species was first described as Leucadendron oleaefolium in the Kungliga Vetenskaps Academiens Handlingar (Transactions of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences) in 1766 by Peter Jonas Bergius. He based this description on a dried specimen that was donated to him by the director of the Swedish East India Company Michael Grubb, who had purchased a collection of dried plants in 1764 in the Dutch Cape Colony from Johann Andreas Auge on a return trip from China.[2][7] Carl Peter Thunberg described in 1781 another specimen as Protea crinita, which Carl Linnaeus the Younger renamed to Protea criniflora later during that same year. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck described a third specimen as Protea venosa in 1792. In 1809, Joseph Knight published a book titled On the cultivation of the plants belonging to the natural order of Proteeae, that contained an extensive revision of the Proteaceae attributed to Richard Anthony Salisbury. Salisbury assigned Thunberg's specimen to his new genus Leucadendrum and called it Leucadendrum criniflorum. It is assumed that Salisbury had based his review on a draft he had seen of a paper called On the natural order of plants called Proteaceae that Robert Brown was to publish in 1810. Brown assigned the specimens of Bergius and Thunberg to the genus Leucospermum as L. oleaefolium and L. crinitum, and added a description of a further specimen as L. molle. The French botanist Jean Poiret assigned that last specimen to the genus Protea in 1816, making the new combination P. mollis. Ernst Gottlieb von Steudel assigned crinitum in 1841 to the genus Leucadendron. Heinrich Wilhelm Buek created the names Leucospermum penicillatum and L. cryptanthum in a book by Johann Franz Drège from 1843, and Carl Meissner provided in 1856 a description for L. penicillatum. Otto Kuntze moved molle and penicillatum in 1891 to Leucadendron. Michel Gandoger finally added Leucospermum schinzianum in 1913. John Patrick Rourke in 1970, regards all these names as synonymous.[2][8] During the 1970s, the International Botanical Congress decided to replace all instances of compounding by the genitive "ae" by "i", thus changing the spelling of the name of this species to Leucospermum oleifolium.[9] L. oleifolium has been assigned to the section Crinitae.[10] The species name oleifolium means olive-leaf.[11]

Distribution and ecology

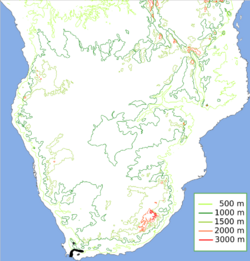

Leucospermum oleifolium ranges from Rooiels in the south, via the Kogelberg Nature Reserve, Hottentots Holland Mountains, Franschhoek, Villiersdorp to the Haweqwa Nature Reserve, and an isolated population around Bainskloof Pass in the north, and eastwards along the Riviersonderend Mountains to Tyger Hoek. It can grown on very well-drained coastal rocks at only 50 m (150 ft) from the high tide line but also on cool peaty slopes at 900 m (3,000 ft) elevation. It is found in the winter rain zone in Fynbos on weathered Table Mountain Sandstone, but only where the local mean annual precipitation is at least 75 cm (30 in). L. oleifolium grows in a dense sclerophyll vegetations consisting mainly of other Proteaceae, Erica species and Restionaceae. In the south of its range, hundreds of individuals huddle together, but towards the north and east the plants become more isolated from each other.[2] The flowers are self-sterile. When the shrubs are in flower, many Cape sugarbirds Promerops cafer and several species of sunbirds visit and pollinate the flowers. The small insects that are drawn to the abundant nectar flow during the early morning, provide an additional treat for the birds. Each flower head only produces a few large, hard nut-like seeds, which are collected by ants and stored underground. In the fynbos, where this species grows, fires occur naturally every one or two decades, and few flame pincushions survive. When afterwards the rain carries specific chemicals that are created by the fire underground, the seeds germinate and the species is so "resurrected". The burnt biomass also provides nutrients to the soil which may assist new growth.[3]

References

- ↑ Rebelo, A.G.; Mtshali, H.; von Staden, L. (2020). "Leucospermum oleifolium". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T157950152A157950157. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T157950152A157950157.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/157950152/157950157. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Rourke, John Patrick (1970). Taxonomic Studies on Leucospermum R.Br.. pp. 236–241. https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/item/26077/thesis_sci_Rourke_1967.pdf.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Leucospermum oleifolium". http://pza.sanbi.org/leucospermum-oleifolium.

- ↑ "Leucospermum oleifolium". https://www.ispotnature.org/communities/southern-africa/view/observation/725297/leucospermum-oleifolium-.

- ↑ "Compilation Leucospermum crinitum". http://plants.jstor.org/compilation/leucospermum.crinitum?searchUri=filter%3Dname%26so%3Dps_group_by_genus_species%2Basc%26Query%3DLeucospermum%2Boleaefolium.

- ↑ Johnson, L.A.S.; Briggs, Barbara G. (1975). "On the Proteaceae—the evolution and classification of a southern family". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 70 (2): 106. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1975.tb01644.x.

- ↑ Gunn, Mary; Codd, L.E.W. (1981). Botanical Exploration Southern Africa. Flora of Southern Africa. Introductory volume to the Flora of Southern Africa. Pretoria: Botanical Research Institute. p. 83.

- ↑ Brown, Robert (1810). "On the Proteaceae of Jussieu". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 10: 15–226 [104]. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1810.tb00013.x. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/757268.

- ↑ International Association for Plant Taxonomy (2012). "IX. Orthography and gender of names". International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code). p. art. 60.8. http://www.iapt-taxon.org/nomen/main.php?page=art60.

- ↑ "Identifying Pincushions". https://www.proteaatlas.org.za/pincushid.htm.

- ↑ Criley, Richard A. (2010). "2". in Jules Janick. Leucospermum: Botany and Horticulture. Horticultural Reviews. 61. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470650721. https://books.google.com/books?id=lVlilno_NacC&q=Leucospermum+elaiosome&pg=PA34.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q5974033 entry

|