Biology:Lumbricus terrestris

| Lumbricus terrestris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| Class: | Clitellata |

| Order: | Opisthopora |

| Family: | Lumbricidae |

| Genus: | Lumbricus |

| Species: | L. terrestris

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lumbricus terrestris | |

Lumbricus terrestris is a large, reddish worm species thought to be native to Western Europe, now widely distributed around the world (along with several other lumbricids). In some areas where it is an introduced species, some people consider it to be a significant pest for out-competing native worms.[1]

Through much of Europe, it is the largest naturally occurring species of earthworm, typically reaching 20 to 25 cm in length when extended.

Common names

Because it is widely known, L. terrestris goes under a variety of common names. In Britain, it is primarily called the common earthworm or lob worm (though the name is also applied to a marine polychaete). In North America, the term nightcrawler (or vitalis) is also used, and more specifically Canadian Nightcrawler, referring to the fact that the large majority of these worms sold commercially (usually as fishing bait) are from Southern Ontario. In Canada , it is also called the dew worm, or "Grandaddy Earthworm". In several Germanic languages, it is called variants of "rain worm", for example in German Gemeiner Regenwurm ("common rain worm") or in Danish Stor regnorm ("large rain worm"). In the rest of the world, many references are just to the scientific name, though with occasional reference to the above names.

Although this is not the most abundant earthworm, even in its native range, it is a very conspicuous and familiar earthworm species in garden and agricultural soils of the temperate zone, and is frequently seen on the surface, unlike most other earthworms. It is also used as the example earthworm for millions of biology students around the world, even in areas where the species does not exist. However, 'earthworm' can be a source of confusion since, in most of the world, other species are more typical. For example, through much of the unirrigated temperate areas of the world, the "common earthworm" is actually Aporrectodea (=Allolobophora) trapezoides, which in those areas is a similar size and dark colour to L. terrestris.

Description

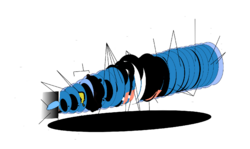

Lumbricus terrestris is relatively large, pinkish to reddish-brown in colour, generally 110–200 millimetres (4.3–7.9 in) in length and about 7–10 millimetres (0.28–0.39 in) in diameter. It has around 120–170 segments, often 135–150. The body is cylindrical in the cross section, except for the broad, flattened posterior section. Head end dark brown to reddish brown lateral, dorsal pigmentation fading towards the back.[1]

The worm has a hydrostatic skeleton and moves by longitudinal and circular muscular contractions. Setae – tiny hair-like projections – provide leverage against the surrounding soil. Surface movements on moist, flat terrain were reported at a speed of 20 m/h and, based on measurements of the length of the trail, nocturnal activity away from the burrow was estimated at up to 19 m during a single surface foray. Such movement is apparent during and after heavy rainfall and usually happens when people become aware of relatively large numbers of earthworms in, for example, urban ecosystems. This form of activity is often considered a way to escape floods and waterlogged burrows. However, this cannot be the case since L. terrestris, like other earthworms, can live in oxygenated water for long periods of time, stretching to weeks. Under less severe environmental conditions where air temperature and moisture are sufficient, the worm often moves around on the surface. This may be driven by resource availability or the desire to avoid mating with close relatives.[2]

Ecology

Lumbricus terrestris is a deep-burrowing anecic earthworm,[3] that is, it builds deep vertical burrows and surfaces to feed, as opposed to burrowing through the soil for its food as endogeic species. It removes litter from the soil surface, pulling it down into the mineral layer, and deposit casts of mixed organic and mineral material on the soil surface.[3] It lives in semi-permanent burrows and can reside in or escape to deeper soil layers.[4]

Its activity is limited by temperature and humidity. High soil and night air temperatures inhibit activity, as do low night moisture and dry soil. During such times, particularly in the summer, the worms will retreat to the deepest parts of their burrows. Winter temperatures can also reduce activity, while activity in maritime climates can continue through winter.[1]

Lumbricus terrestris can strongly influence soil fungi, creating distinctive micro-habitats called middens, which strongly affect the spatial distribution of plant litter and litter-dwelling animals on the soil surface.[5] In the soil system, L. terrestris worm casts have a relationship with plants which can be seen in such scenarios such as in plant propagation from seed or clone. Worm casts initiate root development, root biomass, and in effect, increase root percentage as opposed to the soil and soil systems without worm casts.[6]

In parts of Europe, notably the Atlantic fringe of northwestern Europe, it is now locally endangered due to predation by the New Zealand flatworm (Arthurdendyus triangulatus)[7] and the Australian flatworm (Australoplana sanguinea),[8] two predatory flatworms accidentally introduced from New Zealand and Australia . These predators are very efficient earthworm eaters, being able to survive for lengthy periods with no food, so still persist even when their prey has dropped to unsustainably low populations. In some areas, this is having a seriously adverse effect on the soil structure and quality. The soil aeration and organic material mixing previously done by the earthworms has ceased in some areas.

Diet

Lumbricus terrestris is a detritivore that eats mainly dead leaves on the soil floor and A-horizon mineral soil.[1] Preference is associated with high concentrations of calcium and likely nitrogen. As a result, ash, basswood and aspen are most favored,[9] followed by sugar maple and maple varieties. Oak is less palatable due to its low concentration of calcium, but will be eaten if no higher calcium leaves are available.[3][10]

While they generally feed on plant material, they have been observed feeding on dead insects, soil micro-organisms,[11] and feces.[12]

Reproduction

Lumbricus terrestris is an obligatorily biparental, simultaneous hermaphrodite worm,[13] that reproduces sexually with individuals mutually exchanging sperm.[3] Copulation occurs on the soil surface, but partners remain anchored in their burrow and mating is preceded by repeated mutual burrow visits between neighbors. Additionally, when mates separate, one of them can be pulled out of its burrow.[14] Mating frequency is relatively high (once every 7–11 days). The relative size of the mate, the distance from the presumed mates, the chance of being dragged to the surface, and the size-related fecundity all tend to play key roles in the mating behavior of the nightcrawler.[14]

Sperm is stored for as long as 8 months, and mated individuals produce cocoons for up to 12 months after the mating.[3] Fertilization takes place in the cocoon and the cocoon is deposited in a small chamber in the soil adjacent to the parental burrow. After a few weeks, young worms emerge and begin to feed in the soil. In the early juvenile phase, the worms do not develop the vertical burrows typical of adults. Adulthood is likely to require a minimum of one year of development, with reproductive maturity reached in the second year.[1] The natural lifespan of L. terrestris is unknown, though individuals have lived for six years in captivity.[15]

As an invasive species in North America

Lumbricus terrestris is considered invasive in the north central United States. It does not do well in tilled fields because of pesticide exposure, physical injuries from farm equipment and a lack of nutrients.[16][17] It thrives in fence rows and woodlots and can lead to reductions in native herbaceous and tree regrowth.[18][19]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "Lumbricus terrestris". CAB International. https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/109385.

- ↑ Butt, Kevin R.; Nuutinen, Visa (2005). "The dawn of the dew worm". Biologist 52 (4): 1–7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Lumbricus terrestris". GISD. http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=1555.

- ↑ Valckx, J.; Govers, Gerard; Hermy, Martin; Muys, Bart (2011). "Optimizing Earthworm Sampling in Ecosystems". in A. Karaca. Biology of Earthworms. 24. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 19–38. ISBN 978-3-642-14635-0. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/34526597.pdf.

- ↑ Orazova, Maral Kh.; Semenova, Tatyana A.; Tiunov, Alexei V. (2003). "The microfungal community of Lumbricus terrestris middens in a linden (Tilia cordata) forest". Pedobiologia 47 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1078/0031-4056-00166. ISSN 0031-4056. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/223663295. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ Tomati, U.; Grappelli, A.; Galli, E. (1 January 1988). "The hormone-like effect of earthworm casts on plant growth" (in en). Biology and Fertility of Soils 5 (4): 288–294. doi:10.1007/BF00262133. ISSN 1432-0789. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00262133.

- ↑ Jones, H. D.; Santoro, Giulio; Boag, Brian; Neilson, Roy (2001). "The diversity of earthworms in 200 Scottish fields and the possible effect of New Zealand land flatworms (Arthurdendyus triangulatus) on earthworm populations" (in en). Annals of Applied Biology 139 (1): 75–92. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.2001.tb00132.x. ISSN 1744-7348. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-7348.2001.tb00132.x.

- ↑ Santoro, Giulio; Jones, Hugh D. (January 2001). "Comparison of the earthworm population of a garden infested with the Australian land flatworm (Australoplana sanguinea alba) with that of a non-infested garden". Pedobiologia 45 (4): 313–328. doi:10.1078/0031-4056-00089.

- ↑ Knollenberg, Wesley G.; Merritt, Richard W.; Lawson, Daniel L. (January 1985). "Consumption of Leaf Litter by Lumbricus terrestris (Oligochaeta) on a Michigan Woodland Floodplain". American Midland Naturalist 113 (1): 1–6. doi:10.2307/2425341. ISSN 0003-0031. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2425341. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ Suárez, Esteban R.; Fahey, Timothy J.; Yavitt, Joseph B.; Groffman, Peter M.; Bohlen, Patrick J. (February 2006). "Patterns of Litter Disappearance in a Northern Hardwood Forest Invaded By Exotic Earthworms". Ecological Applications 16 (1): 154–165. doi:10.1890/04-0788. ISSN 1051-0761. PMID 16705969. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1890/04-0788. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ Doug Collicutt. "Biology of the Night Crawler". NatureNorth. http://www.naturenorth.com/fall/ncrawler/Night_Crawlers_03.html.

- ↑ Fosgate, O.T.; Babb, M.R. (June 1972). "Biodegradation of Animal Waste by Lumbricus terrestris". Journal of Dairy Science 55 (6): 870–872. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(72)85586-3. ISSN 0022-0302. PMID 5032211.

- ↑ Butt, Kevin R.; Nuutinen, Visa (1998). "Reproduction of the earthworm Lumbricus terrestris Linné after the first mating". Canadian Journal of Zoology 76 (1): 104–109. doi:10.1139/z97-179. ISSN 0008-4301. http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/10.1139/z97-179. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Michiels, N. K. (September 2001). "Precopulatory mate assessment in relation to body size in the earthworm Lumbricus terrestris: avoidance of dangerous liaisons?". Behavioral Ecology 12 (5): 612–618. doi:10.1093/beheco/12.5.612. ISSN 1465-7279.

- ↑ "Earthworm Research Group (at the University of Central Lancashire):Frequently Asked Questions". http://www.uclan.ac.uk/scitech/earthworm_research/faqs.php.

- ↑ "Earthworm populations and species distributions under no-till and conventional tillage in Indiana and Illinois". Soil Biol Biochem 29 (3–4): 613–615. 1997. doi:10.1016/s0038-0717(96)00187-3.

- ↑ "Long-term trends in earthworm populations of cropped experimental watershed in Ohio, USA". Pedobiologia 43: 713–719. 1999. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258394858.

- ↑ "Earthworm invasion into previously earthworm-free temperate and boreal forests". Biol Invasions 8 (6): 1235–1245. 2006. doi:10.1007/s10530-006-9019-3.

- ↑ "Exotic European earthworm invasion dynamics in northern hardwood forests of Minnesota, USA". Ecol Appl 15 (3): 848–860. 2005. doi:10.1890/03-5345.

External links

- "Exotic Earthworms in Minnesota Hardwood Forests". http://files.dnr.state.mn.us/ecological_services/nongame/projects/consgrant_reports/2002_Frelich_sign2.pdf.

- Wise, Scott (2 September 2012). "Biologists trying to figure why giant earthworm grew so big". CBS 6, WTVR-TV. http://wtvr.com/2012/09/02/giant-earthworm/.

Further reading

- McTavish, Michael J.; Basiliko, Nathan; Sackett, Tara E. (December 2013). "Environmental Factors Influencing Immigration Behaviors of the Invasive Earthworm Lumbricus terrestris". Canadian Journal of Zoology 91 (12): 859–865. doi:10.1139/cjz-2013-0153.

Wikidata ☰ Q30092 entry

|