Biology:Paternal mtDNA transmission

In genetics, paternal mtDNA transmission and paternal mtDNA inheritance refer to the incidence of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) being passed from a father to his offspring. Paternal mtDNA inheritance is observed in a small proportion of species; in general, mtDNA is passed unchanged from a mother to her offspring,[1] making it an example of non-Mendelian inheritance. In contrast, mtDNA transmission from both parents occurs regularly in certain bivalves.

In animals

Paternal mtDNA inheritance in animals varies. For example, in Mytilidae mussels, paternal mtDNA "is transmitted through the sperm and establishes itself only in the male gonad."[2][3][4] In testing 172 sheep, "The Mitochondrial DNA from three lambs in two half-sib families were found to show paternal inheritance."[5] An instance of paternal leakage resulted in a study on chickens.[6] There has been evidences that paternal leakage is an integral part of mitochondrial inheritance of Drosophila simulans.[7]

In humans

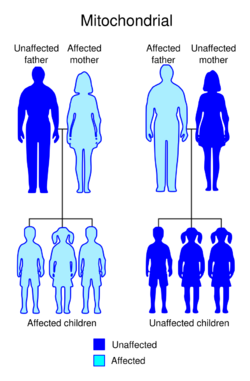

In human mitochondrial genetics, there is debate over whether or not paternal mtDNA transmission is possible. Many studies hold that paternal mtDNA is never transmitted to offspring.[8] This thought is central to mtDNA genealogical DNA testing and to the theory of mitochondrial Eve. The fact that mitochondrial DNA is maternally inherited enables researchers to trace maternal lineage far back in time. Y chromosomal DNA, paternally inherited, is used in an analogous way to trace the agnate lineage.

| “ | Since the father's mtDNA is located in the sperm midpiece (the mitochondrial sheath), which is lost at fertilization, all children of the same mother are hemizygous for maternal mtDNA and are thus identical to each other and to their mother. Because of its cytoplasmic location in eukaryotes, mtDNA does not undergo meiosis and there is normally no crossing-over, hence there is no opportunity for introgression of the father's mtDNA. All mtDNA is thus inherited maternally; mtDNA has been used to infer the pedigree of the well-known "mitochondrial Eve."[9] | ” |

In sexual reproduction, paternal mitochondria found in the sperm are actively decomposed, thus preventing "paternal leakage". Mitochondria in mammalian sperm are usually destroyed by the egg cell after fertilization. In 1999 it was reported that paternal sperm mitochondria (containing mtDNA) are marked with ubiquitin to select them for later destruction inside the embryo.[10] Some in vitro fertilization (IVF) techniques, particularly intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) of a sperm into an oocyte, may interfere with this.

It is now understood that the tail of the sperm, which contains additional mtDNA, may also enter the egg. This had led to increased controversy about the fate of paternal mtDNA.

| “ | Over the last 5 years, there has been considerable debate as to whether there is recombination in human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (for references, see Piganeau and Eyre-Walker, 2004). That debate appears to have finally come to an end with the publication of some direct evidence of recombination. Schwartz and Vissing (2002) presented the case of a 28-year-old man who had both maternal and paternally derived mtDNA in his muscle tissue – in all his other tissues he had only maternally derived mtDNA. It was the first time that paternal leakage and, consequently, heteroplasmy was observed in human mtDNA. In a recent paper, Kraytsberg et al (2004) take this observation one step further, and claim to show that there has been recombination between the maternal and paternal mtDNA in this individual.[11] | ” |

Some sources state that so little paternal mtDNA is transmitted as to be negligible ("At most, one presumes it must be less than 1 in 1000, since there are 100 000 mitochondria in the human egg and only 100 in the sperm (Satoh and Kuroiwa, 1991)."[11]) or that paternal mtDNA is so rarely transmitted as to be negligible ("Nevertheless, studies have established that paternal mtDNA is so rarely transmitted to offspring that mtDNA analyses remain valid..."[12]). A few studies indicate that, very rarely, a small portion of a person's mitochondria can be inherited from the father.[13][14]

The controversy about human paternal leakage was summed up in the 1996 study Misconceptions about mitochondria and mammalian fertilization: Implications for theories on human evolution, which was peer-reviewed and printed in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.[15] According to the study's abstract:

| “ | In vertebrates, inheritance of mitochondria is thought to be predominantly maternal, and mitochondrial DNA analysis has become a standard taxonomic tool. In accordance with the prevailing view of strict maternal inheritance, many sources assert that during fertilization, the sperm tail, with its mitochondria, gets excluded from the embryo. This is incorrect. In the majority of mammals—including humans—the midpiece mitochondria can be identified in the embryo even though their ultimate fate is unknown. The "missing mitochondria" story seems to have survived—and proliferated—unchallenged in a time of contention between hypotheses of human origins, because it supports the "African Eve" model of recent radiation of Homo sapiens out of Africa. | ” |

The mixing of maternal and paternal mtDNA was thought to have been found in chimpanzees in 1999[16] and in humans in 1999[17] and 2018. This last finding is significant, as biparental mtDNA was observed in subsequent generations in three different families leading to the conclusion that, although the maternal transmission dogma remains strong, there is evidence that paternal transmission does exist and there is a probably a mechanism which, if elucidated, can be a new tool in the reproductive field (e.g. avoiding mitochondrial replacement therapy, and just using this mechanism so that the offspring inherit the paternal mitochondria).[18] However, there has been only a single documented case among humans in which as much as 90% of a single tissue type's mitochondria was inherited through paternal transmission.[19]

According to the 2005 study More evidence for non-maternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA?,[20] heteroplasmy is a "newly discovered form of inheritance for mtDNA. Heteroplasmy introduces slight statistical uncertainty in normal inheritance patterns."[21] Heteroplasmy may result from a mutation during development which is propagated to only a subset of the adult cells, or may occur when two slightly different mitochondrial sequences are inherited from the mother as a result of several hundred mitochondria being present in the ovum. However, the 2005 study states:[20]

| “ | Multiple types (or recombinant types) of quite dissimilar mitochondrial DNA from different parts of the known mtDNA phylogeny are often reported in single individuals. From re-analyses and corrigenda of forensic mtDNA data, it is apparent that the phenomenon of mosaic or mixed mtDNA can be ascribed solely to contamination and sample mix up. | ” |

A study published in PNAS in 2018 titled Biparental Inheritance of Mitochondrial DNA in Humans has found paternal mtDNA in 17 individuals from three unrelated multigeneration families with a high level of mtDNA heteroplasmy (ranging from 24 to 76%) in a total of 17 individuals.[22]

| “ | A comprehensive exploration of mtDNA segregation in these families shows biparental mtDNA transmission with an autosomal dominantlike inheritance mode. Our results suggest that, although the central dogma of maternal inheritance of mtDNA remains valid, there are some exceptional cases where paternal mtDNA could be passed to the offspring. | ” |

In protozoa

Some organisms, such as Cryptosporidium, have mitochondria with no DNA whatsoever.[23]

In plants

In plants, it has also been reported that mitochondria can occasionally be inherited from the father, e.g. in bananas. Some Conifers also show paternal inheritance of mitochondria, such as the coast redwood, Sequoia sempervirens.

See also

- Y-chromosomal Adam

- Patrilineality

- Matrilineality

- Human mitochondrial genetics

- Human migration

- RecLOH

- List of genetic genealogy topics

References

- ↑ Birky, C. William (2001-12-01). "The Inheritance of Genes in Mitochondria and Chloroplasts: Laws, Mechanisms, and Models". Annual Review of Genetics 35 (1): 125–148. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090231. ISSN 0066-4197. PMID 11700280.

- ↑ Zouros E (December 2000). "The exceptional mitochondrial DNA system of the mussel family Mytilidae". Genes Genet. Syst. 75 (6): 313–8. doi:10.1266/ggs.75.313. PMID 11280005.

- ↑ "The fate of paternal mitochondrial DNA in developing female mussels, Mytilus edulis: implications for the mechanism of doubly uniparental inheritance of mitochondrial DNA". Genetics 148 (1): 341–7. 1 January 1998. doi:10.1093/genetics/148.1.341. PMID 9475744. PMC 1459795. http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/148/1/341.

- ↑ Male and Female Mitochondrial DNA Lineages in the Blue Mussel (Mytilus edulis) Species Group by Donald T. Stewart, Carlos Saavedra, Rebecca R. Stanwood, Amy 0. Ball, and Eleftherios Zouros

- ↑ "Further evidence for paternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA in the sheep (Ovis aries)". Heredity 93 (4): 399–403. October 2004. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800516. PMID 15266295.

- ↑ Michelle Alexander; Simon Y. W. Ho; Martyna Molak; Ross Barnett; Örjan Carlborg; Ben Dorshorst; Christa Honaker; Francois Besnier et al. (September 30, 2015). "Mitogenomic analysis of a 50-generation chicken pedigree reveals a rapid rate of mitochondrial evolution and evidence for paternal mtDNA inheritance". Biology Letters (The Royal Society) 11 (10): 20150561. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0561. PMID 26510672.

- ↑ J N Wolff; M Nafisinia; P Sutovsky; J W O Ballard (September 2012). "Paternal transmission of mitochondrial DNA as an integral part of mitochondrial inheritance in metapopulations of Drosophila simulans". Heredity 110 (1): 57–62. doi:10.1038/hdy.2012.60. PMID 23010820.

- ↑ e.g. "Maternal inheritance of human mitochondrial DNA". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77 (11): 6715–9. November 1980. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.11.6715. PMID 6256757. Bibcode: 1980PNAS...77.6715G.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Medical Anthropology: Health and Illness in the World's Cultures. 1. Cultures. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. 2004. ISBN 978-0-306-47754-6. https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofme0000unse_l4p4.

- ↑ "Ubiquitin tag for sperm mitochondria". Nature 402 (6760): 371–2. November 1999. doi:10.1038/46466. PMID 10586873.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Evolutionary genetics: direct evidence of recombination in human mitochondrial DNA". Heredity 93 (4): 321. October 2004. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800572. PMID 15329668.

- ↑ evolutionary biologist Andrew Merriwether quoted in Debunking a myth about sperm's DNA. (research indicates paternal mitochondrial DNA does enter fertilized egg) by John Travis, Science News, 1/25/1997

- ↑ Mitochondria can be inherited from both parents", New Scientist article on Schwartz and Vissing's report;

"Paternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA". N. Engl. J. Med. 347 (8): 576–80. August 2002. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020350. PMID 12192017. - ↑ "Mitochondria can be inherited from both parents". https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn2716-mitochondria-can-be-inherited-from-both-parents/.

- ↑ "Misconceptions about mitochondria and mammalian fertilization: Implications for theories on human evolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (24): 13859–63. November 1996. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.24.13859. PMID 8943026. Bibcode: 1996PNAS...9313859A.

- ↑ Awadalla P, Eyre-Walker A, Smith JM (December 1999). "Linkage disequilibrium and recombination in hominid mitochondrial DNA". Science 286 (5449): 2524–5. doi:10.1126/science.286.5449.2524. PMID 10617471. as PDF

- ↑ Strauss E (December 1999). "Human genetics. mtDNA shows signs of paternal influence". Science 286 (5449): 2436a–2436. doi:10.1126/science.286.5449.2436a. PMID 10636798.

- ↑ Luo, Shiyu; Valencia, C. Alexander; Zhang, Jinglan; Lee, Ni-Chung; Slone, Jesse; Gui, Baoheng; Wang, Xinjian; Li, Zhuo et al. (2018-11-21). "Biparental Inheritance of Mitochondrial DNA in Humans" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (51): 13039–13044. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810946115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 30478036. Bibcode: 2018PNAS..11513039L.

- ↑ "Paternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA". N. Engl. J. Med. 347 (8): 576–80. 2002. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020350. PMID 12192017.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Bandelt HJ; Kong QP; Parson W; Salas A. (May 27, 2005). "More evidence for non-maternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA?". American Journal of Medical Genetics 42 (12): 957–60. doi:10.1136/jmg.2005.033589. PMID 15923271.

- ↑ Re: Most-recent common ancestor, rastafarispeaks.com

- ↑ Luo, Shiyu; Valencia, C. Alexander; Zhang, Jinglan; Lee, Ni-Chung; Slone, Jesse; Gui, Baoheng; Wang, Xinjian; Li, Zhuo et al. (2018-11-26). "Biparental Inheritance of Mitochondrial DNA in Humans" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (51): 13039–13044. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810946115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 30478036. Bibcode: 2018PNAS..11513039L.

- ↑ "The unusual mitochondrial compartment of Cryptosporidium parvum". Trends Parasitol. 21 (2): 68–74. February 2005. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2004.11.010. PMID 15664529.

External links

- "No evidence for paternal mtDNA transmission to offspring or extra-embryonic tissues after ICSI". Mol. Hum. Reprod. 8 (11): 1046–9. November 2002. doi:10.1093/molehr/8.11.1046. PMID 12397219.

- "The mutation rate in the human mtDNA control region". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66 (5): 1599–609. May 2000. doi:10.1086/302902. PMID 10756141.

- "Mitochondrial disorders". Brain 127 (Pt 10): 2153–72. October 2004. doi:10.1093/brain/awh259. PMID 15358637.

- "The mitochondrial genome in embryo technologies". Reprod. Domest. Anim. 38 (4): 290–304. August 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0531.2003.00448.x. PMID 12887568.

- "Inheritance and recombination of mitochondrial genomes in plants, fungi and animals". New Phytol. 168 (1): 39–50. October 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01492.x. PMID 16159319. (as PDF)

- Paternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA (PDF) by Marianne Schwartz and John Vissing, 2002

- Pickford M (June 2001). "Paradise lost: Mitochondrial eve refuted". Human Evolution 6 (3): 263–8. doi:10.1007/BF02438149.

- PubMed:

|