Biology:Pittosporum angustifolium

| Weeping pittosporum | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

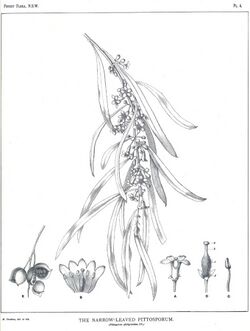

| Drawing by Margaret Flockton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Apiales |

| Family: | Pittosporaceae |

| Genus: | Pittosporum |

| Species: | P. angustifolium

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pittosporum angustifolium | |

| |

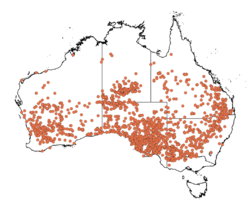

| Occurrence data from AVH | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pittosporum phillyreoides auct. non (DC.) Benth. | |

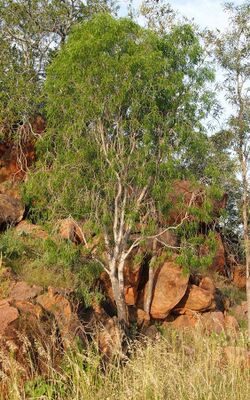

Pittosporum angustifolium (formerly Pittosporum phillyreoides) is a shrub or small tree growing throughout inland Australia. Common names include weeping pittosporum, butterbush, cattle bush, native apricot, apricot tree, gumbi gumbi (or gumby gumby), cumby cumby, meemeei, poison berry bush, and berrigan.

History

Pittosporum angustifolium was first described in 1832 in the Loddiges' The Botanical Cabinet, published by William Loddiges and George Loddiges.[3]

George Bentham combined this species and P. ligustrifolium with P. phillyreoides; however, all three were split in the 2000 revision; the true P. phillyreoides is only found in a narrow coastal strip of northwestern Australia. The weeping foliage of P. angustifolium distinguishes it from the other two taxa.[4]

Description

Pittosporum angustifolium is a slow-growing plant that can reach 10 m (33 ft) in height.[5]

It has pendulous (weeping) branches. The leaves are long and thin, 4 to 12 cm (1.5 to 4.5 in) long and 0.4–1.2 cm (0.16–0.47 in) wide. The small creamish yellow tubular flowers have a pleasant scent. Flowering occurs from late winter to mid spring.[6] Up to 1.4 cm (0.55 in) in diameter, the small round orange fruit resembles an apricot and can remain on the tree for several years. The wrinkled dark red seeds are held within a sticky yellow pulp.[4] Full sun and good drainage is recommended for planting. Seeds germinate in around 17 days without any particular difficulty at 25 °C. There are around 20 viable seeds per gram.

Common names include weeping pittosporum, butterbush, cattle bush, native apricot, apricot tree, gumbi gumbi (or gumby gumby[7]), cumby cumby, meemeei, poison berry bush, and berrigan.[4][5]

Habitat

The species is found in all states of Australia except Tasmania, and in the Northern Territory.[5] It is a widespread plant found across most of inland Australia in mallee communities, alluvial flats, ridges, as well as dry woodland and on loamy, clay or sandy soils, however it is never common.[4]

It is drought- and frost-resistant. It can survive in areas with rainfall as low as 150 mm (5.9 in) per year. A resilient desert species, individuals may live for over a hundred years.[4][8][6]

Uses

Cattle often graze on the leaves, which provide reasonable nutrition. The timber can be used for wood turning.[citation needed]

It is also used as an ornamental plant in the garden, prized for its weeping habit and orange fruit.[5]

Traditional/cultural use

Indigenous Australians used parts of the plant in various ways as medicine.[9][10][11]

Uses varied from place to place and people to people.[5] Some ate or chewed the gum[12] that oozed from branches, while others ground seeds into flour for food. Most commonly, the leaves, seed or wood were steep in hot water and made into a poultice or a tea for medicinal uses, such as to relieve digestive issues, internal pain and cramping, combat chronic fatigue, induce lactation, treat colds, muscle sprains, eczema and other sources of itching.[5][9][13][10]

Despite being known as "native apricot", the bitter fruit is rarely considered a food source.[9]

Medical/therapeutic use

Ongoing scientific research is being carried out internationally, and has begun to identify medically relevant biochemistry present in P. angustifolium, including anti microbial and antibacterial,[14][15] antioxidant,[16][15] antifungal,[17] anti inflammatory,[18] and galactogogue compounds.[19] The findings suggest biochemical compounds from this plant have low toxicity when consumed by humans,[15][20] and could be used to inhibit microbial and fungal growth, bring on lactation, induce apoptosis in cancer cells, protect cells against free radicals and oxidisation, and increase efficacy of commonly prescribed antibiotics; findings are consistent with traditional knowledge and uses.[19][20][14][21][18][22][16][23]

Central Queensland University conducted a long-term project to examine the potential medicinal uses of native Australian plants, in consultation with Ghungalu elder Uncle Steve Kemp, who has been providing plant materials, including P. angustifolium, for the project.[10] Cytotoxic, antioxidant and phenolic compounds have been identified, providing a strong case for the therapeutic benefits and potential cancer fighting properties of the plant.[22][21] Some cytotoxic properties have also been identified in other studies.[24][25]

References

- ↑ "Pittosporum angustifolium". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. https://biodiversity.org.au/nsl/services/rest/name/apni/99376.

- ↑ Loddiges, C., Loddiges, G. & Loddiges, W. (1832), The Botanical Cabinet: t. 1859.

- ↑ Grazyna Paczkowska. "Pittosporum angustifolium". FloraBase, the West Australian Flora. https://florabase.dpaw.wa.gov.au/browse/profile/19744. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Cayzer, Lindy W.; Crisp, Michael D.; Telford, Ian R. H. (2000). "Revision of Pittosporum (Pittosporaceae) in Australia". Australian Systematic Botany (CSIRO) 13 (6): 845. doi:10.1071/sb99021. http://www.publish.csiro.au/paper/SB99021.htm. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Butterbush, Woolshed Thurgoona Landcare Group, https://wtlandcare.org/details/pittosporum-angustifolium/, retrieved 2 May 2022

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Pittosporum angustifolium". Plant Net - NSW Flora Online. NSW Government. https://plantnet.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/cgi-bin/NSWfl.pl?page=nswfl&lvl=sp&name=Pittosporum~angustifolium.

- ↑ Cunningham, Melissa (2019-10-30). "Fake cancer cures top list of complaints". Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney). https://www.smh.com.au/healthcare/fake-cancer-cures-and-snake-venom-extractor-top-list-of-complaints-to-drug-watchdog-20191029-p535cx.html.

- ↑ "Pittosporum angustifolium". FloraBank. http://www.florabank.org.au/lucid/key/species%20navigator/media/html/Pittosporum_angustifolium.htm. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Gumbi Gumbi - Pittosporum angustifolium" (in en-US). https://tuckerbush.com.au/gumbi-gumbi-pittosporum-angustifolium/.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Hines, Jasmine (25 April 2022). "Gumby gumby trees and other Aboriginal medicines to be researched by CQ University". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-04-26/cq-university-traditional-medicine-research-ghungalu-elder/101009154.

- ↑ "Gumbi Gumbi, Bitter Bush an Australian Native Bush Food | Taste Australia Bush Food Shop". https://www.bushfoodshop.com.au/gumbi-gumbi/.

- ↑ Greig, Denise (1998). A Photographic Guide to Trees in Australia. New Holland. p. 128. ISBN 1864363266.

- ↑ Marketing (2022-06-30). "Do you know about the Gumbi Gumbi tree?" (in en-AU). https://www.tascnational.org.au/do-you-know-about-the-gumbi-gumbi-tree/.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Blonk, Baxter; Cock, Ian E. (2019-07-01). "Interactive antimicrobial and toxicity profiles of Pittosporum angustifolium Lodd. extracts with conventional antimicrobials" (in en). Journal of Integrative Medicine 17 (4): 261–272. doi:10.1016/j.joim.2019.03.006. ISSN 2095-4964. PMID 31000372. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2095496419300317.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Beh, Chau Chun; Teoh, Wen Hui (2022). "Recent Advances in the Extraction of Pittosporum angustifolium Lodd. Used in Traditional Aboriginal Medicine: A Mini Review" (in en). Nutraceuticals 2 (2): 49–59. doi:10.3390/nutraceuticals2020004. ISSN 1661-3821.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Bäcker, Christian; Jenett-Siems, Kristina; Bodtke, Anja; Lindequist, Ulrike (2014). "Polyphenolic compounds from the leaves of Pittosporum angustifolium" (in en). Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 55: 101–103. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2014.02.015. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0305197814000635.

- ↑ Phan, Anh Dao Thi; Chaliha, Mridusmita; Hong, Hung Trieu; Tinggi, Ujang; Netzel, Michael E.; Sultanbawa, Yasmina (2020). "Nutritional Value and Antimicrobial Activity of Pittosporum angustifolium (Gumby Gumby), an Australian Indigenous Plant" (in en). Foods 9 (7): 887. doi:10.3390/foods9070887. ISSN 2304-8158. PMID 32640660.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Agatonovic-Kustrin, Snezana; Gegechkori, Vladimir; Morton, David W. (2021-06-21). "The effect of extractive lacto-fermentation on the bioactivity and natural products content of Pittosporum angustifolium (gumbi gumbi) extracts" (in en). Journal of Chromatography A 1647: 462153. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2021.462153. ISSN 0021-9673. PMID 33957349. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021967321002776.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Sadgrove, Nicholas John; Jones, Graham Lloyd (2013-02-13). "Chemical and biological characterisation of solvent extracts and essential oils from leaves and fruit of two Australian species of Pittosporum (Pittosporaceae) used in aboriginal medicinal practice" (in en). Journal of Ethnopharmacology 145 (3): 813–821. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2012.12.019. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 23274743. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378874112008537.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Jones, GL (2014). "THE BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY OF MOLECULAR COMPONENTS FROM PITTOSPORUM ANGUSTIFOLIUM IS CONSISTENT WITH ITS USE IN TRADITIONAL ABORIGINAL MEDICINE". https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273694395.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Mani, Janice S.; Johnson, Joel B.; Hosking, Holly; Ashwath, Nanjappa; Walsh, Kerry B.; Neilsen, Paul M.; Broszczak, Daniel A.; Naiker, Mani (2021-03-25). "Antioxidative and therapeutic potential of selected Australian plants: A review" (in en). Journal of Ethnopharmacology 268: 113580. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.113580. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 33189842. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378874120334681.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Mani, Janice; Johnson, Joel; Hosking, Holly; Walsh, Kerry; Neilsen, Paul; Naiker, Mani (2022-03-01). "In vitro Cytotoxic Properties of Crude Polar Extracts of Plants Sourced from Australia" (in en). Clinical Complementary Medicine and Pharmacology 2 (1): 100022. doi:10.1016/j.ccmp.2022.100022. ISSN 2772-3712.

- ↑ Patil, Anuja (2018). UQ eSpace. doi:10.14264/uql.2018.838. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:40aa632. Retrieved 2023-08-12.

- ↑ Bäcker, Christian; Drwal, Malgorzata N.; Preissner, Robert; Lindequist, Ulrike (2016-04-01). "Inhibition of DNA–Topoisomerase I by Acylated Triterpene Saponins from Pittosporum angustifolium Lodd." (in en). Natural Products and Bioprospecting 6 (2): 141–147. doi:10.1007/s13659-016-0087-5. ISSN 2192-2209. PMID 26803837. PMC 4805651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13659-016-0087-5.

- ↑ Bäcker, Christian; Jenett-Siems, Kristina; Siems, Karsten; Wurster, Martina; Bodtke, Anja; Lindequist, Ulrike (2014-06-01). "Cytotoxic Saponins from the Seeds of Pittosporum angustifolium" (in en). Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 69 (5–6): 191–198. doi:10.5560/znc.2014-0011. ISSN 1865-7125. PMID 25069157. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.5560/znc.2014-0011/html.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q7199137 entry

|