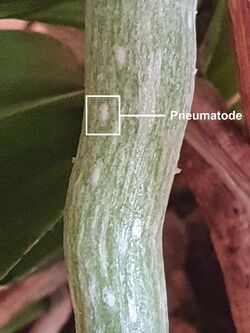

Biology:Pneumatode

In botany, pneumatodes are air-containing structures in plant roots.[1] Their function is to allow gaseous exchange in root tissues. This can be beneficial to semi-aquatic plants, such as neo-tropical palms.[2] Plants with photosynthetic roots, such as epiphytic orchids like Dendrophylax lindenii also possess these structures. They play a role in fungal interactions.[3]

Etymology

The name of the structure is derived from the Greek word πνεῦμα (pneûma), meaning breath and ὁδός (hodós), meaning pathway.[4]

Fungal interactions

Fungal infections of plants may begin through penetration of the roots through pneumatodes.[5]

Functional analogy to stomata

Pneumatodes are considered as a special type of cyclocytic stomata. The entire structure may rise above the adjacent epidermis. The pneumatodes may function as double structures for gas exchange and liquid water elimination (guttation).[6] Leafless orchids with photosynthetic roots rely on the gas exchange through pneumatodes for photosynthesis.

Taxonomic importance

These structures are characteristic for different species and can be used to differentiate between them. These features can be used to distinguish between palm species.[7] They can also be used in the field of paleobotany, as the structures may be preserved in fossilized roots.[8]

References

- ↑ Rosa Belarbi-Halli, Jean Dexheimer, and François Mangenot. Le pneumatode chez Phoenix dactylifera L. I. Structure et ultrastructure. Canadian Journal of Botany. 61(5): 1367-1376. doi:10.1139/b83-146

- ↑ J Balick, M. (1989). The Diversity Of Use Of Neotropical Palms.

- ↑ Chomicki, G., Bidel, L. P., & Jay-Allemand, C. (2014). Exodermis structure controls fungal invasion in the leafless epiphytic orchid Dendrophylax lindenii (Lindl.) Benth. ex Rolfe. Flora-Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 209(2), 88-94.

- ↑ Jaeger, Edmund Carroll (1959). A source-book of biological names and terms. Springfield, Illinois: Thomas. ISBN 0-398-06179-3.

- ↑ Chinchilla, C. M. Fusarium Wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. elaeidis) In Oil Palm: A Rather Weak Pathogen?.

- ↑ Rolleri, C., Deferrari, A. M., & del Carmen Lavalle, M. (1994). Epidermis y estomas porociclocíticos en Christensenia-cumingiana Crist (Marattiaceae-Marattiales-Eusporangiopsida). Revista del Museo de La Plata, 14(98), 207-218.

- ↑ Balick, M. J. (1984). Ethnobotany of Palms in the Neotropics. Advances in Economic Botany, 1, 9–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43931365

- ↑ Plaziat, J. C. (1995). Modern and fossil mangroves and mangals: their climatic and biogeographic variability. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 83(1), 73-96.

|