Biology:Posterior parietal cortex

| Posterior parietal cortex | |

|---|---|

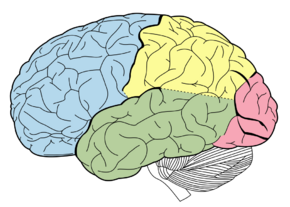

Lobes of the brain. Parietal lobe is yellow, and the posterior portion is near the red region. | |

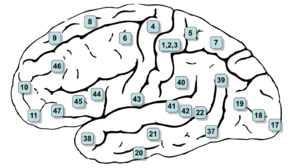

Lateral surface of the brain with Brodmann's areas numbered. (#5 and #7 in upper right) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cortex parietalis posterior |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The posterior parietal cortex (the portion of parietal neocortex posterior to the primary somatosensory cortex) plays an important role in planned movements, spatial reasoning, and attention.

Damage to the posterior parietal cortex can produce a variety of sensorimotor deficits, including deficits in the perception and memory of spatial relationships, inaccurate reaching and grasping, in the control of eye movement, and inattention. The two most striking consequences of PPC damage are apraxia and hemispatial neglect.[1]

Anatomy

(Posterior parietal cortex (light green) is shown at the posterior area of the parietal lobe.)

(Posterior parietal cortex (light green) is shown at the posterior area of the parietal lobe.)

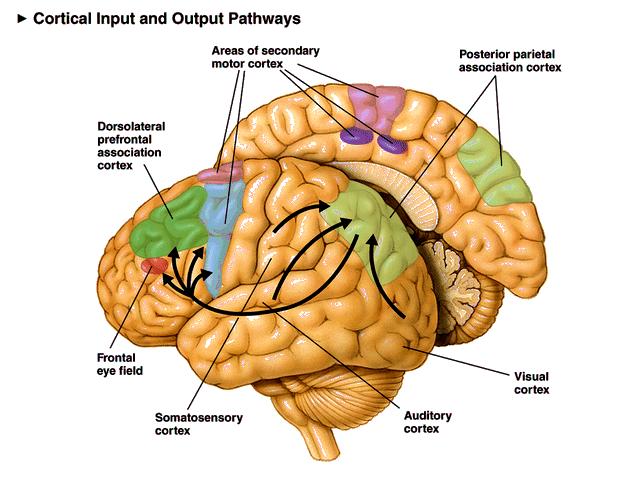

The posterior parietal cortex receives input from the three sensory systems that play roles in the localization of the body and external objects in space: the visual system, the auditory system, and the somatosensory system. In turn, much of the output of the posterior parietal cortex goes to areas of frontal motor cortex: the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, various areas of the secondary motor cortex, and the frontal eye field.

The posterior parietal cortex is divided by the intraparietal sulcus to form the dorsal superior parietal lobule and the ventral inferior parietal lobule.[2][3][4] Brodmann area 7 is part of the superior parietal lobule,[2][5] but some sources include Brodmann area 5.[5] The inferior parietal lobule is further subdivided into the supramarginal gyrus, the temporoparietal junction, and the angular gyrus.[2][3][4] The inferior parietal lobule corresponds to Brodmann areas 39 and 40.[2][4]

Functions

Motor

The posterior parietal cortex has been understood to have separate representations for different motor effectors (e.g. arm vs. eye).[6]

In addition to separation based on effector type, some regions are activated during both decision and execution, while other regions are only active during execution. In one study, single cell recordings showed activity in parietal reach region while non-human primates decided whether to reach or make a saccade to a target, and activity persisted during the chosen movement if and only if the monkey chose to make a reaching movement. However, cells in area 5d were only active after the decision was made to reach with the arm.[7] Another study found that neurons in area 5d only encoded the next movement in a sequence of reach movements, and not reach movements later in the sequence.[8]

In another single-cell recording experiment, neurons in parietal reach region exhibited responses consistent with either of two target locations in a sequence of planned reaching movements, suggesting that different parts of a planned sequence of locations can be represented in parallel in parietal reach region.[9]

Posterior parietal cortex appears to be involved in learning motor skills. In a PET study, researchers had subjects learn to trace a maze with their hand. Activation in right posterior parietal cortex was observed during the task, and decreased activation was associated with the number of errors made.[10] Learning a brain-computer interface produces a similar pattern: posterior parietal cortex activation decreased as subjects became more proficient.[11] One study found that novice artists have increased blood flow in the right posterior parietal compared to expert artists when challenged with art-related tasks.[12]

In a study conducted by neuroscientists at New York University, coherent patterns of firing of neurons in the brain's PPC were associated with coordination of different effectors. The researchers examined neurological activity of macaque monkeys while having them perform a variety of tasks that required them to either reach and to simultaneously employ rapid eye movements (saccades) or to only use saccades. The coherent pattern of the firing of neurons in the PPC were only seen when both the eyes and arms were required to move for the same task, but not for tasks that involved only saccades.[13]

In addition, neurons in posterior parietal cortex encode various aspects of the planned action simultaneously. Kuang and colleagues found that PPC neurons encode not only the planned physical movement, but also the anticipated visual consequence of the intended movement during the planning period.[14]

Other

Studies implicate the temporoparietal junction in exogenous or stimulus-driven attention, while the superior parietal lobule shows transient activation for self-directed switches in attention.[15] Maintaining spatial attention depends on the right posterior parietal cortex; lesions in a region between the intraparietal sulcus and inferior parietal lobule in right PPC were significantly associated with deficits in sustained spatial attention.[16]

Posterior parietal cortex is consistently activated during episodic retrieval, but most hypotheses as to why this is are speculative and usually make some connection between attention and episodic recall.[2][3]

Damage to posterior parietal cortex results in deficits in visual working memory.[17] Patients could name objects that they had previously seen, but were impaired at recognizing previously presented objects, even if these objects had a familiar name.

In a different working memory paradigm, participants were required to make different responses to the same stimuli (letters X/Y) based on previous stimuli.[18] The previous stimuli consisted of lower-level context (letters A/B) and higher level context (numbers 1/2). The lower context specified the appropriate responses to the X/Y stimuli, while the higher level context signaled a change in the effect of the lower level context. Posterior parietal cortex was activated by lower-level context updates but not by higher-level context updates.

Posterior parietal cortex is also activated during reasoning tasks, and some of the areas activated for reasoning tend to also show activation for mathematics or calculation.[19]

There is also evidence indicating that it plays a role in perception of pain.[20]

Recent findings have suggested that feelings of "free will" at least partially originate in this area.[21][22]

References

- ↑ Pinel, John P.J. Biopsychology Seventh Edition. Pearson Education Inc., 2009

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Cabeza R., Ciaramelli E., Olson I. R., Moscovitch M. (2008). "The parietal cortex and episodic memory: an attentional account". Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9 (8): 613–625. doi:10.1038/nrn2459. PMID 18641668.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hutchinson J. B., Uncapher M. R., Wagner A. D. (2009). "Posterior parietal cortex and episodic retrieval: Convergent and divergent effects of attention and memory". Learning & Memory 16 (6): 343–356. doi:10.1101/lm.919109. PMID 19470649.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Martin, R. E. (n.d.). Let’s Get to Know the Parietal Lobes! [PDF]. Retrieved from http://gablab.mit.edu/downloads/Parietal_Primer.pdf

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Scheperjans F., Hermann K., Eickhoff S. B., Amunts K., Schleicher A., Zilles K. (2007). "Observer-Independent Cytoarchitectonic Mapping of the Human Superior Parietal Cortex". Cerebral Cortex 18 (4): 846–867. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhm116. PMID 17644831.

- ↑ Hwang E., Hauschild M., Wilke M., Andersen R. (2012). "Inactivation of the Parietal Reach Region Causes Optic Ataxia, Impairing Reaches but Not Saccades". Neuron 76 (5): 1021–1029. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.030. PMID 23217749.

- ↑ Cui H., Andersen R. A. (2011). "Different Representations of Potential and Selected Motor Plans by Distinct Parietal Areas". Journal of Neuroscience 31 (49): 18130–18136. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.6247-10.2011. PMID 22159124.

- ↑ Li Y., Cui H. (2013). "Dorsal Parietal Area 5 Encodes Immediate Reach in Sequential Arm Movements". Journal of Neuroscience 33 (36): 14455–14465. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1162-13.2013. PMID 24005297.

- ↑ Baldauf D., Cui H., Andersen R. A. (2008). "The Posterior Parietal Cortex Encodes in Parallel Both Goals for Double-Reach Sequences". Journal of Neuroscience 28 (40): 10081–10089. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3423-08.2008. PMID 18829966.

- ↑ Van Mier H. I., Perlmutter J. S., Petersen S. E. (2004). "Functional Changes in Brain Activity During Acquisition and Practice of Movement Sequences". Motor Control 8 (4): 500–520. doi:10.1123/mcj.8.4.500. PMID 15585904.

- ↑ Wander J. D., Blakely T., Miller K. J., Weaver K. E., Johnson L. A., Olson J. D., Ojemann J. G. (2013). "Distributed cortical adaptation during learning of a brain-computer interface task". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (26): 10818–10823. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221127110. PMID 23754426. Bibcode: 2013PNAS..11010818W.

- ↑ Solso, Robert (February 2001). "Brain Activities in a Skilled versus a Novice Artist: An fMRI Study". Leonardo 34 (1): 31–34. doi:10.1162/002409401300052479. http://muse.jhu.edu/article/19635.

- ↑ Dean H., Hagan M., Pesaran B. (2012). "Only Coherent Spiking in Posterior Parietal Cortex Coordinates Looking and Reaching". Neuron 73 (4): 829–841. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.035. PMID 22365554.

- ↑ Kuang, S.; Morel, P.; Gail, A. (2016). "Planning Movements in Visual and Physical Space in Monkey Posterior Parietal Cortex". Cerebral Cortex 26 (2): 731–747. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhu312. PMID 25576535.

- ↑ Behrmann M., Geng J. J., Shomstein S. (2004). "Parietal cortex and attention". Current Opinion in Neurobiology 14 (2): 212–217. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.012. PMID 15082327. https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/6617429.

- ↑ Malhotra P., Coulthard E. J., Husain M. (2009). "Role of right posterior parietal cortex in maintaining attention to spatial locations over time". Brain 132 (3): 645–660. doi:10.1093/brain/awn350. PMID 19158107.

- ↑ Berryhill M. E., Olson I. R. (2008). "Is the posterior parietal lobe involved in working memory retrieval? Evidence from patients with bilateral parietal lobe damage". Neuropsychologia 46 (7): 1767–1774. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.01.009. PMID 18308348.

- ↑ Nee D. E., Brown J. W. (2012). "Dissociable Frontal-Striatal and Frontal-Parietal Networks Involved in Updating Hierarchical Contexts in Working Memory". Cerebral Cortex 23 (9): 2146–2158. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhs194. PMID 22798339.

- ↑ Wendelken C (2015). "Meta-analysis: how does posterior parietal cortex contribute to reasoning?". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8: 1042. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.01042. PMID 25653604.

- ↑ Witting N, Kupers RC, Svensson P, Arendt-Nielsen L, Gjedde A, Jensen TS (2001). "Experimental brush-evoked allodynia activates posterior parietal cortex". Neurology 57 (10): 1817–24. doi:10.1212/wnl.57.10.1817. PMID 11723270.

- ↑ Desmurget M., Reilly K. T., Richard N., Szathmari A., Mottolese C., Sirigu A. (2009). "Movement Intention After Parietal Cortex Stimulation in Humans". Science 324 (5928): 811–813. doi:10.1126/science.1169896. PMID 19423830. Bibcode: 2009Sci...324..811D.

- ↑ Haggard P (2009). "The Sources of Human Volition". Science 324 (5928): 731–733. doi:10.1126/science.1173827. PMID 19423807. Bibcode: 2009Sci...324..731H.

External links

|