Biology:Western swamp turtle

| Western swamp turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pseudemydura umbrina, Western swamp tortoise | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Pleurodira |

| Family: | Chelidae |

| Subfamily: | Pseudemydurinae Gaffney, 1977 |

| Genus: | Pseudemydura Seibenrock, 1901 |

| Species: | P. umbrina

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudemydura umbrina (Seibenrock, 1901)

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

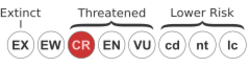

The western swamp turtle or western swamp tortoise (Pseudemydura umbrina) is a critically endangered species of freshwater turtle endemic to a small portion of Western Australia.[4][5] It is the only member of the genus Pseudemydura in the monotypic subfamily Pseudemydurinae.[6]

It is the sister taxon to the subfamily Chelodininae. As a consequence of the greatly altered habitat in the area in which it occurs near Perth, Western Australia, it exists in small fragmented populations, making the species critically endangered.

Taxonomy

The accepted description of the species by Friedrich Siebenrock was published in 1901.[5] The first specimen of the western swamp tortoise was collected by Ludwig Preiss in 1839 and sent to Vienna Museum. There it was labelled "New Holland" and was named Pseudemydura umbrina 1901 by Seibenrock. No further specimens were found until 1953. In 1954, Ludwig Glauert named these specimens Emydura inspectata, but in 1958, Ernest Williams of Harvard University showed that to be a synonym of Pseudemydura umbrina.[7]

Description

Adult males do not exceed a length of 155 mm or a weight of 550 g. Females are smaller, not growing beyond 135 mm in carapace length or a weight of 410 g. Hatchlings have a carapace length of 24–29 mm and weigh between 3.2 and 6.6 g.[7]

The colour of the western swamp turtle varies dependent on age and the environment where it is found. Typical colouration for hatchlings is grey above with bright cream and black below. The colour of adults varies with differing swamp conditions, and varies from medium yellow-brown in clay swamps to almost black with a maroon tinge in the black coffee-coloured water of sandy swamps. Plastron colour is variable, from yellow to brown or occasionally black; often there are black spots on a yellow background with black edges to the scutes. The legs are short and covered in scale-like scutes and the feet have well-developed claws. The short neck is covered with horny tubercles and on the top of the head is a large single scute. It is the smallest chelid found in Australia.

The only other species of freshwater turtle occurring in the southwest of Western Australia is the southwestern snake-necked turtle (Chelodina oblonga). It has a neck equal to or longer than its shell, making the two species from south west Western Australia easily distinguishable.

Distribution

The western swamp turtle has been recorded only in scattered localities on the Swan Coastal Plain in Western Australia, from Perth Airport northwards to near Pearce Royal Australian Air Force Base in the Bullsbrook locality (roughly parallel with the Darling Scarp).[7] Most of this area is now cleared and either urbanised, used for intensive agriculture or mined for clay for brick manufacture.

Conservation

The legal status of the species as listed by the Australian federal and state (W.A.) governments is critically endangered.[8] The IUCN Red List[1] assessed the species as Critically Endangered. The 2007 Red List noted the description as in need of updating.

A recovery plan was first published in 1994 and has been updated since, the most recent version is dated 2010.[7] Threatening processes include small, fragmented populations occurring in nature reserves that are smaller than an individual's home range, predation by the introduced red fox Vulpes vulpes, changed hydrology due to land-use changes and extraction of groundwater, and reducing rainfall due to climate change.

Recovery actions include population monitoring, management of nature reserves, and captive breeding at Perth Zoo[9] and subsequent reintroduction and introduction. This species is notable in conservation history for being the first example of an endangered vertebrate that is being translocated to a distant location (200 kilometers poleward) expressly because of climate change.[10][11] Public appreciation and assistance is supported by The Friends of the Western Swamp Tortoise.[12]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group 1996. Pseudemydura umbrina (errata version published in 2016). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 1996: e.T18457A97271321. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T18457A8294310.en. Downloaded on 31 May 2019.

- ↑ "Appendices | CITES". https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php.

- ↑ Fritz Uwe; Peter Havaš (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World". Vertebrate Zoology 57 (2): 343. ISSN 1864-5755. http://www.cnah.org/pdf_files/851.pdf. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ↑ Rhodin, Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Inverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley; Roger, Bour (2011-12-31). Turtles of the world, 2011 update: Annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution and conservation status. 5. 000.214. doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v4.2011. ISBN 978-0965354097. http://www.iucn-tftsg.org/wp-content/uploads/file/Accounts/crm_5_000_checklist_v4_2011.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Siebenrock, F. (1901) Beschreibung einer neuen Schildkrötengattung aus der Familie Chelydridae von Australien. Sitzungsber. Akademie Wiss. Wien math. nat. Kl., Jahrg. 1901, 248-258.

- ↑ King, J.M., G. Kuchling, & S.D. Bradshaw (1998). Thermal environment, behavior, and body condition of wild Pseudemydura umbrina (Testudines: Chelidae) during late winter and early spring. Herpetologica. 54 (1):103-112.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Burbidge, A. A., G. Kuchling, C. Olejnik & L. Mutter for the Western Swamp Tortoise Recovery Team (2010) Department of Environment and Conservation, Perth. Available at http://www.environment.gov.au/resource/western-swamp-tortoise-pseudemydura-umbrina-recovery-plan-0

- ↑ Pseudemydura umbrina, Species Profile and Threats Database, Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australia.

- ↑ "Western Swamp Tortoise Breeding Program | Perth Zoo". Perthzoo.wa.gov.au. https://perthzoo.wa.gov.au/saving-wildlife/breeding-conservation/western-swamp-tortoise-breeding-program.

- ↑ Wahlquist, Calla (16 August 2016). "Australia's rarest tortoises get new home to save them from climate change". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/aug/17/australias-rarest-tortoises-get-new-home-to-save-them-from-climate-change.

- ↑ Zhuang, Yan (12 December 2022). "Can Australia Save a Rare Reptile by Moving It to a Cooler Place?". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/12/world/australia/assisted-colonization-tortoise.html.

- ↑ "Friends of the Western Swamp Tortoise – FoWST group is an initiative of the Threatened Species Network, through WWF". Westernswamptortoise.com.au. https://www.westernswamptortoise.com.au/.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q2050578 entry

|