Biology:Ricinus

| Ricinus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leaves and inflorescence (male flowers below female flowers) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Euphorbiaceae |

| Subfamily: | Acalyphoideae |

| Tribe: | Acalypheae |

| Subtribe: | Ricininae |

| Genus: | Ricinus L. |

| Species: | R. communis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ricinus communis L.

| |

Ricinus communis, the castor bean[1] or castor oil plant,[2] is a species of perennial flowering plant in the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae. It is the sole species in the monotypic genus, Ricinus, and subtribe, Ricininae. The evolution of castor and its relation to other species are currently being studied using modern genetic tools.[3] It reproduces with a mixed pollination system which favors selfing by geitonogamy but at the same time can be an out-crosser by anemophily (wind pollination) or entomophily (insect pollination).[4]

Its seed is the castor bean, which despite the term is not a bean (as it is not the seed of a member of the family Fabaceae). Castor is indigenous to the southeastern Mediterranean Basin, Eastern Africa, and India, but is widespread throughout tropical regions (and widely grown elsewhere as an ornamental plant).[5]

Castor seed is the source of castor oil, which has a wide variety of uses. The seeds contain between 40% and 60% oil that is rich in triglycerides, mainly ricinolein. The seed also contains ricin, a highly potent water-soluble toxin, which is also present in lower concentrations throughout the plant.

The plant known as "false castor oil plant", Fatsia japonica, is not closely related.

Description

Ricinus communis can vary greatly in its growth habit and appearance. The variability has been increased by breeders who have selected a range of cultivars for leaf and flower colours, and for oil production. It is a fast-growing, suckering shrub that can reach the size of a small tree, around 12 metres (39 feet), but it is not cold hardy.

The glossy leaves are 15–45 centimetres (6–18 inches) long, long-stalked, alternate and palmate with five to twelve deep lobes with coarsely toothed segments. In some varieties they start off dark reddish purple or bronze when young, gradually changing to a dark green, sometimes with a reddish tinge, as they mature. The leaves of some other varieties are green practically from the start, whereas in yet others a pigment masks the green color of all the chlorophyll-bearing parts, leaves, stems and young fruit, so that they remain a dramatic purple-to-reddish-brown throughout the life of the plant. Plants with the dark leaves can be found growing next to those with green leaves, so there is most likely only a single gene controlling the production of the pigment in some varieties.[6] The stems and the spherical, spiny seed capsules also vary in pigmentation. The fruit capsules of some varieties are more showy than the flowers.

The flowers lack petals and are unisexual (male and female) where both types are borne on the same plant (monoecious) in terminal panicle-like inflorescences of green or, in some varieties, shades of red. The male flowers are numerous, yellowish-green with prominent creamy stamens; the female flowers, borne at the tips of the spikes, lie within the immature spiny capsules, are relatively few in number and have prominent red stigmas.[7]

The fruit is a spiny, greenish (to reddish-purple) capsule containing large, oval, shiny, bean-like, highly poisonous seeds with variable brownish mottling. Castor seeds have a warty appendage called the caruncle, which is a type of elaiosome. The caruncle promotes the dispersal of the seed by ants (myrmecochory).

-

Young plant

-

Green variant after blooming, with developing seed capsules

-

Leaf

-

Male flower

-

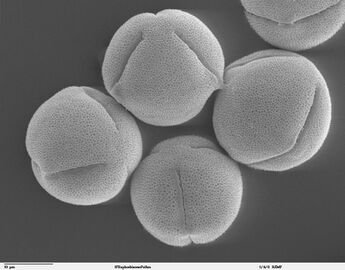

Pollen grains of Ricinus communis

-

Female flower

-

The green capsule dries and splits into three sections, forcibly ejecting seeds

-

Seeds

-

Cotyledons (round) and first true leaves (serrated) on a young plant (about four weeks old)

Chemistry

Three terpenoids and a tocopherol-related compound have been found in the aerial parts of Ricinus. Compounds named (3E,7Z,11E)-19-hydroxycasba-3,7,11-trien-5-one, 6α-hydroxy-10β-methoxy-7α,8α-epoxy-5-oxocasbane-20,10-olide, 15α-hydroxylup-20(29)-en-3-one, and (2R,4aR,8aR)-3,4,4a,8a-tetrahydro-4a-hydroxy-2,6,7,8a-tetramethyl-2-(4,8, 12-trimethyltridecyl)-2H-chromene-5,8-dione were isolated from the methanol extracts of Ricinus communis by chromatographic methods.[8] Partitioned h-hexane fraction of Ricinus root methanol extract resulted in enrichment of two triterpenes: lupeol and urs-6-ene-3,16-dione (erandone). Crude methanolic extract, enriched n-hexane fraction and isolates at doses 100 mg/kg p.o. exhibited significant (P < 0.001) anti-inflammatory activity in carrageenan-induced hind paw oedema model.[9]

Taxonomy

Carl Linnaeus used the name Ricinus because it is a Latin word for tick; the seed is so named because it has markings and a bump at the end that resemble certain ticks. The genus Ricinus[10] also exists in zoology, and designates insects (not ticks) which are parasites of birds; this is possible because the names of animals and plants are governed by different nomenclature codes.[11][12]

The common name "castor oil" probably comes from its use as a replacement for castoreum, a perfume base made from the dried perineal glands of the beaver (castor in Latin).[13] It has another common name, palm of Christ, or Palma Christi, that derives from castor oil's reputed ability to heal wounds and cure ailments.

Ecology

Ricinus communis is the host plant of the common castor butterfly (Ariadne merione), the eri silkmoth (Samia cynthia ricini), and the castor semi-looper moth (Achaea janata). It is also used as a food plant by the larvae of some other species of Lepidoptera, including Hypercompe hambletoni and the nutmeg (Discestra trifolii). A jumping spider Evarcha culicivora has an association with R. communis. They consume the nectar for food and preferentially use these plants as a location for courtship.[14]

Each castor seed has a yellow nodule full of fats one end of the seed that are nutritious for young ants. After hauling their harvest into their nests and pulling off the delicious part, ants discard the rest of the seed into their trash pile, where the future plant starts to grow.[citation needed]

Cultivation

Although Ricinus communis is indigenous to the southeastern Mediterranean Basin, Eastern Africa, and India, today it is widespread throughout tropical regions.[5] In areas with a suitable climate, castor establishes itself easily where it can become an invasive plant and can often be found on wasteland.

It is also used extensively as a decorative plant in parks and other public areas, particularly as a "dot plant" in traditional bedding schemes. If sown early, under glass, and kept at a temperature of around 20 °C (68 °F) until planted out, the castor oil plant can reach a height of 2–3 metres (6.6–9.8 ft) in a year. In areas prone to frost it is usually shorter, and grown as if it were an annual.[5] However, it can grow well outdoors in cooler climates, at least in southern England, and the leaves do not appear to suffer frost damage in sheltered spots, where it remains evergreen.[15] It was used in Edwardian times in the parks of Toronto, Canada. Although not cultivated there, the plant grows wild in the US, notably Griffith Park in Los Angeles.[16]

Cultivars

Cultivars have been developed by breeders for use as ornamental plants (heights refer to plants grown as annuals) and for commercial production of castor oil.[7]

- Ornamental cultivars

- 'Carmencita' has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit[17][18]

- 'Carmencita Bright Red' has red stems, dark purplish leaves and red seed pods;

- 'Carmencita Pink' has green leaves and pink seed pods

- 'Gibsonii' has red-tinged leaves with reddish veins and bright scarlet seed pods

- 'New Zealand Purple' has plum colored leaves tinged with red, plum colored seed pods turn to red as they ripen

- (All the above grow to around 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) tall as annuals.)[5]

- 'Impala' is compact (only 1.2 metres or 3.9 feet tall) with reddish foliage and stems, brightest on the young shoots

- 'Red Spire' is tall (2–3 metres or 6.6–9.8 feet) with red stems and bronze foliage

- 'Zanzibarensis' is also tall (2–3 metres or 6.6–9.8 feet), with large, mid-green leaves (50 centimetres or 20 inches long) that have white midribs[7]

- Cultivars for oil production

- 'Hale' was launched in the 1970s for the US state of Texas.[19] It is short (up to 1.2 m or 3 ft 11 in) and has several racemes

- 'Brigham' is a variety with reduced ricin content adapted for Texas, US. It grows up to 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) and has 10% of the ricin content of 'Hale'

- 'BRS Nordestina' was developed by Brazil's Embrapa in 1990 for hand harvest and semi-arid environments

- 'BRS Energia" was developed by Embrapa in 2004 for mechanised or hand harvest

- 'GCH6' was developed by Sardarkrushinagar Dantiwada University, India, 2004: it is resistant to root rot and tolerant to fusarium wilt

- 'GCH5' was developed by Sardarkrushinagar Dantiwada University, 1995. It is resistant to fusarium wilt

- 'Abaro' was developed by the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research's Essential Oils Research Center for hand harvest

- 'Hiruy' was developed by the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research's Melkassa and Wondo Genet Agricultural Research Centers for hand harvest during 2010/2011

Allergenicity and toxicity

Ricinus is extremely allergenic, and has an OPALS allergy scale rating of 10 out of 10. The plant is also a very strong trigger for asthma, and allergies to Ricinus are commonplace and severe.[20]

The castor oil plant produces abundant amounts of very light pollen, which easily become airborne and can be inhaled into the lungs, triggering allergic reactions. The sap of the plant causes skin rashes. People who are allergic to the plant can also develop rashes from touching the leaves, flowers, or seeds. They can also have cross-allergic reactions to latex sap from the related Hevea brasiliensis plant.[20]

The toxicity of raw castor beans is due to the presence of ricin. Although the lethal dose in adults is considered to be four to eight seeds, reports of actual poisoning are relatively rare.[21] According to the Guinness World Records, this is the world's most poisonous common plant.[22]

If ricin is ingested, symptoms commonly begin within two to four hours, but may be delayed by up to 36 hours. These include a burning sensation in mouth and throat, abdominal pain, purging and bloody diarrhea. Within several days there is severe dehydration, a drop in blood pressure and a decrease in urine. Unless treated, death can be expected to occur within 3–5 days; however, in most cases a full recovery can be made.[23][24]

Poisoning occurs when animals, including humans, ingest broken castor beans or break the seed by chewing: intact seeds may pass through the digestive tract without releasing the toxin.[23] The toxin provides the castor oil plant with some degree of natural protection from insect pests such as aphids. Ricin has been investigated for its potential use as an insecticide.[25]

Commercially available cold-pressed castor oil is not toxic to humans in normal doses, whether internal or external.[26]

Uses

Castor oil has many uses in medicine and other applications. An alcoholic extract of the leaf was shown to protect the liver of laboratory rats from damage from certain poisons.[27][28] Methanolic extracts of the leaves of Ricinus communis were used in antimicrobial testing against eight pathogenic bacteria in rats and showed antimicrobial properties.

The pericarp of Ricinus showed central nervous system effects in mice at low doses. At high doses mice quickly died.[29] A water extract of the root bark showed analgesic activity in rats.[29] Antihistamine and anti-inflammatory properties were found in ethanolic extract of Ricinus communis root bark.[30] Castor oil and the plant's roots and leaves are used in the ancient Indian medicinal system of Ayurveda for various diseases, and it has been investigated in a few limited studies for its potential as an anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory herbal medicine.[31][32][33]

Modern commercial usage

Global castor seed production is around two million tons per year. Leading producing areas are India (with over three-quarters of the global yield), China and Mozambique, and it is widely grown as a crop in Ethiopia. There are several active breeding programmes.

| Country | Production (tonnes) | Footnote | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 1,196,680 | |||

| Mozambique | 85,089 | F | ||

| China | 36,000 | * | ||

| Brazil | 16,349 | |||

| Ethiopia | 11,157 | * | ||

| Vietnam | 7,000 | * | ||

| South Africa | 6,721 | F | ||

| Paraguay | 6,000 | * | ||

| Thailand | 1,588 | * | ||

| Pakistan | 1,107 | * | ||

| World | 1,407,588 | A | ||

| No symbol = official figure, F = FAO estimate, * = Unofficial/Semi-official/mirror data, A = Aggregate (may include official, semi-official or estimates) | ||||

Other modern uses of natural, blended, or chemically altered castor products include:

- As a non-freezing, antimicrobial, pressure-resistant lubricant for special purposes, either of latex or metals, or as a lubricating component of fuels.[34]

- As sources of various chemical feedstocks.[35]

- As a raw material for some varieties of biodiesel.

- As attractively patterned, low-cost personal adornments, such as non-durable necklaces and bracelets. Holes must not be drilled in the beans to make beads. The outer shell protects the water from the poison. Wearing castors beans has been known to cause rashes, and worse.

- As a component of many cosmetics.

- As an anti-microbial. The high percentage of ricinoleic acid residues in castor oil and its derivatives, inhibits many microbes, whether viral, bacterial or fungal. They accordingly are useful components of many ointments and similar preparations.

- As the major raw material (in oil form) for polyglycerol polyricinoleate, a modifier that improves the flow characteristics of cocoa butter in the manufacture of chocolate bars, and thereby reduces the costs .

- As a repellent for moles and voles in lawns.

Historical usage

Ancient uses

Castor seeds have been found in Egyptian tombs dating back to 4000 BC; the slow-burning oil was mostly used to fuel lamps. Herodotus and other Ancient Greece travellers noted the use of castor seed oil for lighting, body ointments, and improving hair growth and texture. Cleopatra is reputed to have used it to brighten the whites of her eyes. The Ebers Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian medical treatise believed to date from 1552 BC. Translated in 1872, it describes castor oil as a laxative.[36]

The use of castor bean oil (eranda) in India has been documented since 2000 BC in lamps and in local medicine as a laxative, purgative, and cathartic in Unani, Ayurvedic, siddha and other ethnomedical systems. Traditional Ayurvedic and siddha medicine considers castor oil the king of medicinals for curing arthritic diseases. It is regularly given to children to treat infections with parasitic worms.[37] Modern medical research suggests the purgative action induced by castor oil helps clear intestines of parasites.[38]

The ancient Romans had a variety of medicinal/cosmetic uses for both the seeds and the leaves of Ricinus communis. The naturalist Pliny the Elder cited the poisonous qualities of the seeds, but mentioned that they could be used to form wicks for oil lamps (possibly if crushed together), and the oil for use as a laxative and lamp oil.[39] He also recommends the use of the leaves as follows:

"The leaves are applied topically with vinegar for erysipelas, and fresh-gathered, they are used by themselves for diseases of the mamillæ [breasts] and de- fluxions; a decoction of them in wine, with polenta and saffron, is good for inflammations of various kinds. Boiled by themselves, and applied to the face for three successive days, they improve the complexion."[40]

In Haiti it is called maskreti,[41] where the plant is turned into a red oil that is then given to newborns as a purgative to cleanse the insides of their first stools.[42]

Castor seed and its oil have also been used in China for centuries, mainly prescribed in local medicine for internal use or use in dressings.[43]

Uses in punishment

Castor oil was used as an instrument of coercion by the paramilitary Blackshirts under the regime of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and by the Spanish Civil Guard in Francoist Spain. Dissidents and regime opponents were forced to ingest the oil in large amounts, triggering severe diarrhea and dehydration, which could ultimately cause death. This punishment method was originally thought of by Gabriele D'Annunzio, the Italian poet and Fascist supporter, during the First World War.[44]

Other uses

Extract of Ricinus communis exhibited acaricidal and insecticidal activities against the adult of Haemaphysalis bispinosa (Acarina: Ixodidae) and hematophagous fly Hippobosca maculata (Diptera: Hippoboscidae).[45]

Members of the Bodo tribe of Bodoland in Assam, India, use the leaves of the plant to feed the larvae of muga and endi silkworms.

Castor oil is an effective motor lubricant and has been used in internal combustion engines, including those of World War I airplanes, some racing cars and some model airplanes. It has historically been popular for lubricating two-stroke engines due to high resistance to heat compared to petroleum-based oils. It does not mix well with petroleum products, particularly at low temperatures, but mixes better with the methanol-based fuels used in glow model engines. In total-loss-lubrication applications, it tends to leave carbon deposits and varnish within the engine. It has been largely replaced by synthetic oils that are more stable and less toxic.

Jewellery can be made of castor beans, particularly necklaces and bracelets.[46] Holes must not be drilled into the castor beans as the shell protects the wearer from the ricin.[citation needed] Any chips in the shell can cause poisoning of the wearer.[citation needed] Pets who chew the jewellery can become ill.[46]

Ricinus communis leaves are used in botanical printing (also known as ecoprinting) in Asia. When bundled with cotton or silk fabric and steamed, the leaves can produce a green-colored imprint. [47][better source needed]

See also

References

- ↑ "Ricinus communis". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=RICO3.

- ↑ "Ricinus communis: Castor oil plant". Dept. of Plant Sciences, Oxford. https://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/bol/plants400/profiles/QR/Ricinuscommunis. "The castor oil plant is one of the few major crops to have an origin in Africa."

- ↑ "Euphorbiaceae (spurge) genomics". Institute for Genome Sciences. University of Maryland Medical School. http://www.igs.umaryland.edu/?q=content/euphorbiaceae-spurge-genomics.

- ↑ Rizzardo, RA; Milfont, MO; Silva, EM; Freitas, BM (December 2012). "Apis mellifera pollination improves agronomic productivity of anemophilous castor bean (Ricinus communis)". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 84 (4): 1137–45. doi:10.1590/s0001-37652012005000057. PMID 22990600.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Phillips, Roger; Rix, Martyn (1999). Annuals and Biennials. London: Macmillan. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-333-74889-3.

- ↑ e.g. "PROTA published species". http://database.prota.org/publishedspeciesEn.htm.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Christopher Brickell, ed (1996). The Royal Horticultural Society A-Z Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. London: Dorling Kindersley. pp. 884–885. ISBN 978-0-7513-0303-2.

- ↑ Tan Q.-G.; Cai X.-H.; Dua Z.-Z.; Luo X.-D. (2009). "Three terpenoids and a tocopherol-related compound from Ricinus communis". Helvetica Chimica Acta 92 (12): 2762–8. doi:10.1002/hlca.200900105.

- ↑ Srivastava, Pooja; Jyotshna; Gupta, Namita; Kumar Maurya, Anil; Shanker, Karuna (2013). "New anti-inflammatory triterpene from the root of Ricinus communis". Natural Product Research 28 (5): 306–311. doi:10.1080/14786419.2013.861834. PMID 24279342.

- ↑ Charles de Geer, 1752-1778 Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire des insectes, digital facsimile at the Gallica website.

- ↑ Oliver, Paul M.; Lee, Michael S.Y. (2010). "The botanical and zoological codes impede biodiversity research by discouraging publication of unnamed new species". Taxon 59 (4): 1201–1205. doi:10.1002/tax.594020. ISSN 0040-0262.

- ↑ "Animal Nomenclature". https://projects.ncsu.edu/cals/course/zo150/mozley/nomencla.html.

- ↑ "The Complex Case of Castor's Etymology". http://www.billcasselman.com/cwod_archive/beaver_castor_two.htm.

- ↑ Cross, Fiona R., and Robert R. Jackson. "Odour‐mediated response to plants by evarcha culicivora, a blood‐feeding jumping spider from East Africa." New Zealand Journal of Zoology 36.2 (2009): 75-80.

- ↑ "Castor Bean, Ricinus communis" (in en-US). https://wimastergardener.org/article/castor-bean-ricinus-communis/.

- ↑ Toronto Star, 9 June 1906, p. 17

- ↑ "RHS Plantfinder – Ricinus communis 'Carmencita'". https://www.rhs.org.uk/Plants/106235/i-Ricinus-communis-i-Carmencita/Details.

- ↑ "AGM Plants – Ornamental". Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 88. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/pdfs/agm-lists/agm-ornamentals.pdf.

- ↑ The Cattleman. 1961. p. 126. https://books.google.com/books?id=oEcUAQAAMAAJ. ""Hale" is a dwarf-internode castor bean variety developed in the cooperative castorbean program of the United States Department of Agriculture and the Texas Agricultural Experiment Station. It is resistant to bacterial leaf spot and Alternaria leaf spot"

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ogren, Thomas (2015). The Allergy-Fighting Garden. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-1-60774-491-7.

- ↑ "Castor bean poisoning". Am J Emerg Med 4 (3): 259–61. May 1986. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(86)90080-X. PMID 3964368.

- ↑ Guinness World Records 2017. London, UK: Guinness World Records Limited. 2016. p. 43.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Ricinus communis cake poisoning in a dog". Vet Hum Toxicol 44 (3): 155–6. June 2002. PMID 12046967.

- ↑ Ricinus communis (Castor bean)—Cornell University 2008. "Castorbean". http://www.ansci.cornell.edu/plants/castorbean.html.

- ↑ Union County College: Biology: Plant of the Week: Castor Bean Plant

- ↑ Irwin R (March 1982). "NTP technical report on the toxicity studies of Castor Oil (CAS No. 8001-79-4) In F344/N Rats And B6C3F1 Mice (Dosed Feed Studies)". Toxic Rep Ser 12: 1–B5. PMID 12209174.

- ↑ Joshi M.; Waghmare S.; Chougule P.; Kanase A. (2004). "Extract of Ricinus communis leaves mediated alterations in liver and kidney functions against single dose of CCl4 induced liver necrosis in albino rats.". Journal of Ecophysiology and Occupational Health 4 (3–4): 169–173. ISSN 0972-4397.

- ↑ Kalaiselvi P.; Anuradha B.; Parameswari C.S. (2003). "Protective effect of Ricinus communis leaf extract against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity". Biomédicine 23 (1–2): 97–105.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Williamson E. M. (ed) "Major Herbs of Ayurveda", Churchill Livingstone 2002

- ↑ "Effect of Solanum nigrum and Ricinus communis extracts on histamine and carrageenan-induced inflammation in the chicken skin". Cellular and Molecular Biology (Noisy-le-grand) 56 (Suppl): OL1239–51. 2010. PMID 20158977.

- ↑ Abdul, WaseemMohammed; Hajrah, NahidH; Sabir, JamalS.M.; Al-Garni, SalehM; Sabir, MeshaalJ; Kabli, SalehA; Saini, KulvinderSingh; Bora, RoopSingh (2018). "Therapeutic role of Ricinus communis L. and its bioactive compounds in disease prevention and treatment" (in en). Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine 11 (3): 177. doi:10.4103/1995-7645.228431. ISSN 1995-7645. http://www.apjtm.org/text.asp?2018/11/3/177/228431.

- ↑ Ziaei, Atousa; Sahranavard, Shamim; Gharagozlou, Mohammad Javad; Faizi, Mehrdad (2016-05-03). "Preliminary investigation of the effects of topical mixture of Lawsonia inermis L. and Ricinus communis L. leaves extract in treatment of osteoarthritis using MIA model in rats". DARU Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 24 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s40199-016-0152-y. ISSN 2008-2231. PMID 27142000.

- ↑ Taur, Dnyaneshwar J; Waghmare, Maruti G; Bandal, Rajendra S; Patil, Ravindra Y (April 2011). "Antinociceptive activity of Ricinus communis L. leaves". Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 1 (2): 139–141. doi:10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60012-9. ISSN 2221-1691. PMID 23569744.

- ↑ R. M. Mortier; S. T. Orszulik (6 December 2012). Chemistry and Technology of Lubricants. Springer. pp. 226–. ISBN 978-1-4615-3272-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=uKKNBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA226.

- ↑ Castor Oil World

- ↑ Tunaru, S; Althoff, TF; Nusing, RM; Diener, M; Offermanns, S (2012). "Castor Oil Induces Laxation and Uterus Contraction via Ricinoleic Acid Activating Prostaglandin EP3 Receptors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (23): 9179–9184. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201627109. PMID 22615395. Bibcode: 2012PNAS..109.9179T.

- ↑ Rekha, D. (2013). "Study of medicinal plants used from koothanoallur and marakkadai, Thiruvarur district of Tamil Nadu, India.". Hygeia Journal for Drugs and Medicines 5 (1): 164–170.

- ↑ McGaw, L. J.; Jäger, A. K.; van Staden, J. (2000-09-01). "Antibacterial, anthelmintic and anti-amoebic activity in South African medicinal plants" (in en). Journal of Ethnopharmacology 72 (1): 247–263. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00269-5. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 10967478. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378874100002695.

- ↑ John Bostock & H.T. Riley (1855). "Pliny, the Natural History Chapter 41. – Castor Oil, 16 Remedies". https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D23%3Achapter%3D41.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder. Natural History. p. Chapter 41, Book 23.41.

- ↑ Quiros-Moran, Dalia, ed (2009). Guide to Afro-Cuban Herbalism. AuthorHouse. p. 347. ISBN 9781438980973. https://books.google.com/books?id=OeA1-Of-LscC&pg=PA347. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Comprehensive Maternity Nursing: Perinatal and Women's Health. Jones and Bartlett Publishers. 1990. p. 122. ISBN 9780867204216. https://books.google.com/books?id=FelsAAAAMAAJ&q=maskreti+newborn+haiti. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Scarpa, Antonio; Guerci, Antonio (1982). "Various uses of the castor oil plant (Ricinus communis L.) a review". Journal of Ethnopharmacology 5 (2): 117–137. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(82)90038-1. ISSN 0378-8741. PMID 7035750.

- ↑ Petersen, Jens (1982), "Violence in Italian Fascism, 1919–25", Social Protest, Violence and Terror in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-century Europe (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK): pp. 275–299, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-16941-2_17, ISBN 978-1-349-16943-6

- ↑ "Evaluation of botanical extracts against Haemaphysalis bispinosa Neumann and Hippobosca maculata Leach". Parasitology Research 107 (3): 585–92. August 2010. doi:10.1007/s00436-010-1898-7. PMID 20467752.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Growing danger: Toxic plants pose pet threat". 2009-06-10. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/31130769/ns/health-pet_health/t/growing-danger-toxic-plants-pose-pet-threat/#.VEOiHxaNrIU.

- ↑ (in en) how to make ECOPRINT DIY, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F7zPTcR1bFE, retrieved 2022-10-23

Further reading

- Everitt, J.H.; Lonard, R.L.; Little, C.R. (2007). Weeds in South Texas and Northern Mexico. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 978-0-89672-614-7.

External links

- Ricinus at Curlie

- A Bean Called Castor Can Cut Carbon & Fuel the Future

- Ricinus communis L. – at Purdue University

- Castor beans – at Purdue University

- Ricinus communis (castor bean) at Cornell University

- Ricinus communis in Wildflowers of Israel

- Castor oil plant Flowers in Israel

Wikidata ☰ {{{from}}} entry

|