Biology:Statistical potential

In protein structure prediction, a statistical potential or knowledge-based potential is an energy function derived from an analysis of known protein structures in the Protein Data Bank. Many methods exist to obtain such potentials; two notable methods are the quasi-chemical approximation (due to Miyazawa and Jernigan[1]) and the potential of mean force (due to Sippl [2]). Although the obtained energies are often considered as approximations of the free energy, this physical interpretation is incorrect.[3][4] Nonetheless, they have been applied with a limited success in many cases [5] because they frequently correlate with actual (physical) free energy differences.

Assigning an energy

Possible features to which an energy can be assigned include torsion angles (such as the angles of the Ramachandran plot), solvent exposure or hydrogen bond geometry. The classic application of such potentials is however pairwise amino acid contacts or distances. For pairwise amino acid contacts, a statistical potential is formulated as an interaction matrix that assigns a weight or energy value to each possible pair of standard amino acids. The energy of a particular structural model is then the combined energy of all pairwise contacts (defined as two amino acids within a certain distance of each other) in the structure. The energies are determined using statistics on amino acid contacts in a database of known protein structures (obtained from the Protein Data Bank).

Sippl's potential of mean force

Overview

Many textbooks present the potentials of mean force (PMFs) as proposed by Sippl [2] as a simple consequence of the Boltzmann distribution, as applied to pairwise distances between amino acids. This is incorrect, but a useful start to introduce the construction of the potential in practice. The Boltzmann distribution applied to a specific pair of amino acids, is given by:

where is the distance, is the Boltzmann constant, is the temperature and is the partition function, with

The quantity is the free energy assigned to the pairwise system. Simple rearrangement results in the inverse Boltzmann formula, which expresses the free energy as a function of :

To construct a PMF, one then introduces a so-called reference state with a corresponding distribution and partition function , and calculates the following free energy difference:

The reference state typically results from a hypothetical system in which the specific interactions between the amino acids are absent. The second term involving and can be ignored, as it is a constant.

In practice, is estimated from the database of known protein structures, while typically results from calculations or simulations. For example, could be the conditional probability of finding the atoms of a valine and a serine at a given distance from each other, giving rise to the free energy difference . The total free energy difference of a protein, , is then claimed to be the sum of all the pairwise free energies:

where the sum runs over all amino acid pairs (with ) and is their corresponding distance. In many studies does not depend on the amino acid sequence.[6]

Intuitively, it is clear that a low value for indicates that the set of distances in a structure is more likely in proteins than in the reference state. However, the physical meaning of these PMFs have been widely disputed since their introduction.[3][4][7][8] The main issues are the interpretation of this "potential" as a true, physically valid potential of mean force, the nature of the reference state and its optimal formulation, and the validity of generalizations beyond pairwise distances.

Justification

Analogy with liquid systems

The first, qualitative justification of PMFs is due to Sippl, and based on an analogy with the statistical physics of liquids.[9] For liquids,[10] the potential of mean force is related to the radial distribution function , which is given by:

where and are the respective probabilities of finding two particles at a distance from each other in the liquid and in the reference state. For liquids, the reference state is clearly defined; it corresponds to the ideal gas, consisting of non-interacting particles. The two-particle potential of mean force is related to by:

According to the reversible work theorem, the two-particle potential of mean force is the reversible work required to bring two particles in the liquid from infinite separation to a distance from each other.[10]

Sippl justified the use of PMFs - a few years after he introduced them for use in protein structure prediction [9] - by appealing to the analogy with the reversible work theorem for liquids. For liquids, can be experimentally measured using small angle X-ray scattering; for proteins, is obtained from the set of known protein structures, as explained in the previous section. However, as Ben-Naim writes in a publication on the subject:[4]

[...]the quantities, referred to as `statistical potentials,' `structure based potentials,' or `pair potentials of mean force', as derived from the protein data bank, are neither `potentials' nor `potentials of mean force,' in the ordinary sense as used in the literature on liquids and solutions.

Another issue is that the analogy does not specify a suitable reference state for proteins.

Analogy with likelihood

Baker and co-workers [11] justified PMFs from a Bayesian point of view and used these insights in the construction of the coarse grained ROSETTA energy function. According to Bayesian probability calculus, the conditional probability of a structure , given the amino acid sequence , can be written as:

is proportional to the product of the likelihood times the prior . By assuming that the likelihood can be approximated as a product of pairwise probabilities, and applying Bayes' theorem, the likelihood can be written as:

where the product runs over all amino acid pairs (with ), and is the distance between amino acids and . Obviously, the negative of the logarithm of the expression has the same functional form as the classic pairwise distance PMFs, with the denominator playing the role of the reference state. This explanation has two shortcomings: it is purely qualitative, and relies on the unfounded assumption the likelihood can be expressed as a product of pairwise probabilities.

Reference ratio explanation

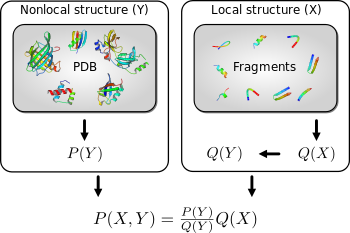

Expressions that resemble PMFs naturally result from the application of probability theory to solve a fundamental problem that arises in protein structure prediction: how to improve an imperfect probability distribution over a first variable using a probability distribution over a second variable , with .[5] Typically, and are fine and coarse grained variables, respectively. For example, could concern the local structure of the protein, while could concern the pairwise distances between the amino acids. In that case, could for example be a vector of dihedral angles that specifies all atom positions (assuming ideal bond lengths and angles). In order to combine the two distributions, such that the local structure will be distributed according to , while the pairwise distances will be distributed according to , the following expression is needed:

where is the distribution over implied by . The ratio in the expression corresponds to the PMF. Typically, is brought in by sampling (typically from a fragment library), and not explicitly evaluated; the ratio, which in contrast is explicitly evaluated, corresponds to Sippl's potential of mean force. This explanation is quantitive, and allows the generalization of PMFs from pairwise distances to arbitrary coarse grained variables. It also provides a rigorous definition of the reference state, which is implied by . Conventional applications of pairwise distance PMFs usually lack two necessary features to make them fully rigorous: the use of a proper probability distribution over pairwise distances in proteins, and the recognition that the reference state is rigorously defined by .

Applications

Statistical potentials are used as energy functions in the assessment of an ensemble of structural models produced by homology modeling or protein threading - predictions for the tertiary structure assumed by a particular amino acid sequence made on the basis of comparisons to one or more homologous proteins with known structure. Many differently parameterized statistical potentials have been shown to successfully identify the native state structure from an ensemble of "decoy" or non-native structures.[12][13][14][15][16][17] Statistical potentials are not only used for protein structure prediction, but also for modelling the protein folding pathway.[18][19]

See also

References

- ↑ "Estimation of effective interresidue contact energies from protein crystal structures: quasi-chemical approximation". Macromolecules 18 (3): 534–552. 1985. doi:10.1021/ma00145a039.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Sippl MJ (1990). "Calculation of conformational ensembles from potentials of mean force. An approach to the knowledge-based prediction of local structures in globular proteins". J Mol Biol 213 (4): 859–883. doi:10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80269-4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Statistical potentials extracted from protein structures: how accurate are they?". J Mol Biol 257 (2): 457–469. 1996. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1996.0175. PMID 8609636.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Ben-Naim A (1997). "Statistical potentials extracted from protein structures: Are these meaningful potentials?". J Chem Phys 107 (9): 3698–3706. doi:10.1063/1.474725.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Flower, Darren R., ed (2010). "Potentials of mean force for protein structure prediction vindicated, formalized and generalized". PLoS ONE 5 (11): e13714. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013714. PMID 21103041.

- ↑ "Are database-derived potentials valid for scoring both forward and inverted protein folding?". Protein Eng 8 (9): 849–858. 1995. doi:10.1093/protein/8.9.849.

- ↑ "Knowledge-based potentials–back to the roots". Biochemistry Mosc 63: 247–252. 1998.

- ↑ Shortle D (2003). "Propensities, probabilities, and the Boltzmann hypothesis". Protein Sci 12 (6): 1298–1302. doi:10.1110/ps.0306903. PMID 12761401.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Helmholtz free energies of atom pair interactions in proteins". Fold Des 1 (4): 289–98. 1996. doi:10.1016/s1359-0278(96)00042-9. PMID 9079391.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Chandler D (1987) Introduction to Modern Statistical Mechanics. New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

- ↑ "Assembly of protein tertiary structures from fragments with similar local sequences using simulated annealing and Bayesian scoring functions". J Mol Biol 268 (1): 209–225. 1997. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1997.0959. PMID 9149153.

- ↑ Miyazawa S., Jernigan RL. (1996). "Residue–Residue Potentials with a Favorable Contact Pair Term and an Unfavorable High Packing Density Term, for Simulation and Threading". J Mol Biol 256 (3): 623–644. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1996.0114. PMID 8604144.

- ↑ "Distance Dependent, Pair Potential for Protein Folding: Results from Linear Optimization". Proteins 41: 40–46. 2000. doi:10.1002/1097-0134(20001001)41:1<40::aid-prot70>3.3.co;2-l.

- ↑ "Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures". Protein Sci 15 (11): 2507–2524. 2006. doi:10.1110/ps.062416606. PMID 17075131.

- ↑ "Protein structure evaluation using an all-atom energy based empirical scoring function". J Biomol Struct Dyn 23 (4): 385–406. 2006. doi:10.1080/07391102.2006.10531234. PMID 16363875.

- ↑ Sippl MJ (1993). "Recognition of Errors in Three-Dimensional Structures of Proteins". Proteins 17 (4): 355–62. doi:10.1002/prot.340170404. PMID 8108378.

- ↑ "An empirical energy function for threading protein sequence through the folding motif". Proteins 16 (1): 92–112. 1993. doi:10.1002/prot.340160110. PMID 8497488.

- ↑ Kmiecik S and Kolinski A (2007). "Characterization of protein-folding pathways by reduced-space modeling". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (30): 12330–12335. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702265104. PMID 17636132.

- ↑ "De novo prediction of protein folding pathways and structure using the principle of sequential stabilization". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 (43): 17442–17447. 2012. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209000109. PMID 23045636.

|