Biology:Vaccine Revolt

The Vaccine Revolt (Portuguese: Revolta da Vacina) was a popular riot that took place between 10 and 16 November 1904 in the city of Rio de Janeiro, then the capital of Brazil. Its immediate pretext was a law that made vaccination against smallpox compulsory, but it is also associated with deeper causes, such as the urban reforms being carried out by mayor Pereira Passos and the sanitation campaigns led by physician Oswaldo Cruz.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the urban planning of the city of Rio de Janeiro, inherited from the colonial period and the Empire, no longer matched its status as a capital and center of economic activities. In addition, the city suffered from serious public health problems. Diseases such as smallpox, bubonic plague and yellow fever ravaged the population and worried the authorities. In order to modernize the city and control such epidemics, president Rodrigues Alves initiated a series of urban and sanitary reforms that changed the city's geography and the daily life of its population. The architectural changes in the city were the responsibility of engineer Pereira Passos, appointed mayor of the then Federal District. Streets were widened, tenements were destroyed and the poor were removed from their former homes. Doctor Oswaldo Cruz, who took over the General Directorate of Public Health in 1903, was responsible for the sanitation campaign in the city, which aimed to eradicate yellow fever, bubonic plague and smallpox. To this end, in June 1904, the government proposed a law that made vaccinatation mandatory. The law generated heated debates between legislators and the population, and, despite a strong opposition campaign, was approved on 31 October.

The trigger for the revolt was the publication of a project to regulate the application of the mandatory vaccine in the newspaper A Notícia, on 9 January 1904. The project required proof of vaccination for enrollment in schools, for obtaining jobs, travel, accommodations and weddings. It also provided for the payment of fines for those who resisted vaccination. When the proposal leaked to the press, the indignant and upset people started a series of conflicts and demonstrations that lasted for about a week. Although mandatory vaccination triggered the revolt, protests soon began to target public services in general and government representatives, in particular against repressive forces. A group of florianist and positivist soldiers, with the support of some civil sectors, tried to take advantage of popular discontent to carry out a coup d'état in the early hours of 14 to 15 November, which, however, was defeated.

On 16 November, a state of emergency was decreed and mandatory vaccination was suspended. Given the systematic repression and extinguished the triggering cause, the movement ebbed. In the repression that followed the revolt, the police forces arrested a number of suspects and individuals considered to be troublemakers, regardless of whether they were involved in the revolt or not. The total balance was 945 people arrested on Ilha das Cobras, 30 dead, 110 injured and 461 deported to the remote state of Acre.

Background

At the turn of the 19th century, at the same time as the abolitionist movements that put an end to slavery and the monarchy took place, in addition to the revolts that convulsed the first years of the First Brazilian Republic, large contingents of European immigrants and former slaves from the decaying coffee producing zones flocked to Rio de Janeiro, then capital of Brazil.[1] The city underwent a process of industrialization and population growth, rising from 522,651 to 811,444 inhabitants between 1890 and 1906.[2] The pressure for housing led the owners of the large imperial and colonial buildings, which occupied the central region of the city, to divide them internally into several cubicles, transforming them into boarding houses and tenements (cortiços) and renting them out to entire families.[3]

The precarious sanitary conditions favored the proliferation of diseases such as the bubonic plague, smallpox and yellow fever, endemic in Rio de Janeiro, especially in the poorest regions.[1] Epidemics gave Rio de Janeiro the reputation of being a plague-ridden and deadly city, driving away foreigners, fearful of contracting diseases, and the urban planning inherited from the colonial period and the Empire no longer matched its condition as the capital and center of economic activities in Brazil of that period.[4]

In this context, Rodrigues Alves was inaugurated president of Brazil in November 1902. In his first message to Congress, he declared that problems in the capital affected and disturbed national development as a whole, and adopted sanitation and improvement of the port of Rio de Janeiro as priorities for his government.[5][6] Rodrigues Alves had inherited a temporarily stabilized economy from Campos Sales after the Encilhamento crisis, thanks to the recovery of coffee prices on the international market and Sales' austere and unpopular financial policy.[lower-alpha 1][8] Without significantly changing the financial policy of his predecessor, Rodrigues Alves embarked on an intensive program of public works, financed by external resources, which managed to start the economic recovery.[7]

Causes of the revolt

Relying on a large majority in Congress, Rodrigues Alves soon took action to make the sanitation and urban reform works in the city viable. He attributed the task of reforming the port, with discretionary powers and resources, to Lauro Müller, then Minister of Industry, Transport and Public Works.[5] The budget law of 30 December 1902 provided the Ministry of Transport with substantial resources, destined for the restructuring and expansion works of the port, which, in addition to modernizing the existing pier, intended to expand the port facilities of Prainha, passing through Praia de São Cristóvão, to Ponta do Caju. The same law authorized the issuance of bonds with a aiming at increasing the capital intended for investment. It also released any loan that came to be arranged by the contractors in charge of the works, under any terms and with any credit agencies, and even agreed with the demolitions and construction of works parallel to the pier, surrounding or connected to the port facilities, which ensure storage and free and rapid circulation of exchanged goods.[9]

Despite being the most important in the country and one of the busiest on the American continent at the time, the port of Rio de Janeiro still had an old-fashioned and restricted structure, incompatible with its fundamental role in Brazilian economic activity. The limits of the pier and the shallow depth prevented the docking of large international transatlantic ships, which were anchored offshore, forcing a complicated, time-consuming and costly system of transhipment of goods and passengers to smaller vessels. Once the goods were transported to land, the problems continued. The space on the docks was too small to store items intended for the national and international market. The products had to be taken to the railway junctions, which connected Rio de Janeiro to the rest of the country, in coordination with cabotage navigation. The city streets, however, were still colonial alleys, narrow, tortuous, dark and with very steep slopes.[10] Thus, the improvement of the port of Rio de Janeiro also implied a broad urban reform.[11]

Urban reform

Engineer Pereira Passos was nominated as mayor of the Federal District to carry out the necessary reforms. Knowing the extent and urgency of the works he had to carry out and prefiguring the resistance and reactions of the population to the demolitions, Passos demanded full freedom of action to accept the position, without being subject to legal, budgetary or material embarrassments. Rodrigues Alves, through the law of 29 December 1902, created a new statute of municipal organization for the Federal District, attributing broad powers to the mayor.[12]

The law foresaw that the judicial, federal or local authorities could not revoke administrative measures and acts of the municipality, nor grant possessory interdicts against acts of the municipal government exercised for imperative reasons; it ended any bureaucratic control or postponement of the reforms and, in cases of demolition, eviction or interdiction, there would be only one notice posted in the place, providing for penalties against disobedience; it also provided for the eviction of residents in the buildings to be demolished, as well as the removal of their furniture and belongings, which would be done by the police.[13]

At the same time that he led the works, Pereira Passos also took a series of measures aimed at prohibiting and changing the forms of work, leisure and sociability considered incompatible with a cosmopolitan and modern capital.[14] He banned stray dogs and dairy cows from the streets; ordered the beggars to be collected in asylums; prohibited the cultivation of vegetable gardens and grasslands, the raising of pigs, the itinerant sale of lottery tickets; he also ordered people not to spit on the streets and inside vehicles, not to urinate outside urinals, and not to fly kites.[15]

The works on the port were contracted in 1903 with the English firm C. H. Walker, which had built the docks in Buenos Aires, and began in March 1904, comprising in its first part the 600-meter stretch that went from the Mangue to the Gamboa pier. Complementary works on Avenida Central, Avenida do Cais (now Avenida Rodrigues Alves) and the Mangue canal were the responsibility of the federal government itself, under the direction of a commission whose chief engineer was Paulo de Frontin. The expropriations for the construction of the new avenue began in December 1903 and the demolitions in February 1904, when work on the Mangue canal also began. At the same time, the city government was in charge of widening some downtown streets.[16]

By November 1904, the date of the uprising, the demolition of houses to open up Avenida Central had ended and 16 of the new buildings were under construction. The avenue's central axis was inaugurated on 7 September, amidst large parties, already with tram service and electric lighting. The demolition of around 640 buildings had torn, through the most inhabited part of the city, a corridor that ran from the beach to the Passeio Público. Part of the rubble still covered the sides of the avenue.[16] On the same date, the streets of Acre (formerly Prainha), São Bento, Visconde de Inhaúma, Assembleia and Sete de Setembro were being widened. Rua do Sacramento was extended to Avenida Marechal Floriano Peixoto, with the new part named Avenida Passos.[17] The demolition of the old buildings, by then almost all converted into boarding houses and tenements, caused a housing crisis that raised rents and pressured the popular classes towards the suburbs and up the hills that surround the city.[18]

Sanitation measures

In the early 1900s, Rio de Janeiro was an endemic focus for several diseases, including yellow fever, typhoid fever, malaria, smallpox, bubonic plague and tuberculosis. Of these, yellow fever and smallpox caused the greatest number of victims in the capital. The crews and passengers arriving at the port often did not even get off the ships to avoid contracting such diseases. So that the campaign to attract capital, immigrants, technicians and foreign equipment with the improvement of the port could be effectively carried out, it was essential to proceed with the sanitation of the city.[11] Thus, sanitation in Rio de Janeiro maintained an intimate relationship with the improvement of the port and also with urban reform, since the sanitation problem was considered to depend on an architectural remodeling of the city and, consequently, the opening of double access roads and airy communications, replacing the narrow streets, overloaded with intense traffic, without enough ventilation, without trees and flanked by buildings that were considered unhygienic.[19]

Doctor Oswaldo Cruz was in charge of sanitation in the city, assuming the General Directorate of Public Health (DGSP) with the intention of tackling yellow fever, smallpox and the bubonic plague.[20] To this end, he demanded from Rodrigues Alves the most complete freedom of action, in addition to resources for the application of his measures.[21] In 1904, the sanitary services were reformed, suppressing the dual attributions between the municipal and federal governments after the approval of a bill that had already been in process since the previous year.[22] Thus, the DGSP could invade, inspect and demolish houses and buildings, in addition to having a special forum, with a specially appointed judge to resolve issues and overcome resistance.[21]

First, Oswaldo Cruz faced yellow fever, tackling the disease by eliminating mosquitoes and isolating patients in hospitals.[23] He structured his campaign on military bases, using legal instruments of coercion and, to a lesser extent, means of persuasion, such as the "Councils to the People", published in the government press. The city was divided into ten health districts, with health departments, whose personnel were responsible for receiving notifications of patients, administering serums and vaccines, fining and subpoenaing property owners and detecting epidemic outbreaks. The section in charge of maps and epidemiological statistics provided coordinates to the mosquito killer brigades, which roamed the streets neutralizing water deposits with mosquito larvae. Another section purged the houses with sulfur and pyrethrum, after covering them with huge cotton cloths to kill adult mosquitoes. Soon after, Oswaldo Cruz turned to the bubonic plague, which required the extermination of rats and fleas and the cleaning and disinfection of streets and houses. The de-rat control of the city resulted in the issuance of hundreds of subpoenas to property owners requesting them to remove rubble and carry out renovations, especially the waterproofing of the ground and the suppression of basements.[24] To prevent resistance from residents, the brigades were always accompanied by police soldiers. The preferred targets for visits were the poorest and most densely populated areas.[23] DGSP's actions were not well received by the population, especially by the owners of pension houses and tenements considered unhygienic, forced to renovate or demolish them, and by tenants forced to receive public health employees, to leave the houses for disinfection, or even to abandon the dwelling when condemned to demolition.[15]

The fight against smallpox, in turn, depended on vaccination. A bill that made smallpox vaccination mandatory throughout Brazil was presented on 29 June 1904 by senator Manuel José Duarte from Alagoas.[25] The project was approved with 11 votes against, on 20 July, entering the Chamber of Deputies on 18 August and being approved by a large majority at the end of October, becoming law on the 31 of that month.[26] The project generated a heated debate between legislators and the population. While government legislators argued that vaccination was of undeniable and essential interest for public health, opponents considered that the methods of applying the vaccination decree were truculent, and that serums and, above all, their applicators, were unreliable.[27] In the Senate, the biggest opponent of the project was lieutenant-colonel Lauro Sodré, while in the Chamber major Barbosa Lima stood out, both positivist and florianist soldiers.[26] Outside Congress, the fight against mandatory vaccines took place mainly in the press, especially in Correio da Manhã and Commercio do Brazil.[28] During the discussion, several lists of anti-mandatory signatures were sent to Congress. Two of them were organized by the Centro das Classes Operárias, with the signatures of Vicente de Souza, the president, Jansen Tavares, the first secretary, and all the other members of the board. In another list, 78 military personnel appeared, mostly ensign-students at the Military School of Praia Vermelha. In all, 15 thousand signatures were added against the project.[29] After the approval of the bill, the League Against Mandatory Vaccine was founded on 5 November, in a meeting at the Centro das Classes Operárias presided over by Lauro Sodré and Vicente de Souza and with the presence of two thousand people.[30] The League was formed by a coalition of radical republican politicians, ideological factions within the Brazilian Army, and journalists.[31]

There was great popular irritation with the government's actions in the area of public health, especially with regard to house inspections and disinfections. In the justifications of the petitions sent to the Chamber by workers, the invasion of houses, the demand for residents to leave for disinfection, and the damage caused to domestic utensils were mentioned more than once as a reason for complaints.[32] There was also a certain fear about the vaccine itself, and the opposition sought to give the anti-vaccination campaign a moralistic tone, exploiting the idea of house invasions and offending the fathers' honor by forcing their daughters and wives to undress in front of strangers for the application of the vaccine.[33]

The uprising

First demonstrations

On 9 November 1904, the newspaper A Notícia (Rio de Janeiro) published a plan to regulate the application of the mandatory vaccine.[25] The project offered the option of vaccination by a private physician, but the certificate would have to be notarized. In addition, there would be fines for refractory workers and a vaccination certificate would be required for enrollment in schools, access to government jobs, employment in factories, accommodation in hotels and guesthouses, travel, marriage and voting.[34][35] There was a violent reaction on the part of the population, and on the following day large gatherings took over Rua do Ouvidor, Praça Tiradentes and Largo de São Francisco de Paula, where popular speakers spoke against the law and vaccine regulations.[36]

The disturbances started around six in the afternoon, when a group of students started a demonstration in the São Francisco square, where the Polytechnic School was located, making humorous and rhyming speeches. The group walked down Rua do Ouvidor, where the speaker, student Jayme Cohen, preached resistance to the vaccine. A police chief summoned him to go to the police station. There was popular backlash against the arrest. Upon arriving near Tiradentes Square, the group came face to face with police cavalry soldiers, erupting in boos and shouts of "Die the police! Down with the vaccine!". There was, then, conflict with the police forces and attempts to snatch Cohen away. In the end, fifteen people were arrested, including five students and two civil servants. At 7:30 PM the situation returned to normal, with the police remaining on guard at Praça Tiradentes.[37]

On the 11th, demonstrators gathered again in the São Francisco square, summoned by the League Against Mandatory Vaccine. When the League's leaders did not attend, popular speakers gave impromptu speeches. Police authorities were ordered to intervene and, as they approached the demonstration, they were the target of boos and taunts. When the police tried to make the arrests, clashes broke out. Protesters used rubble from the ongoing renovations and armed themselves with iron, sticks and stones.[38] There was a rush and pursuit by the police, extending to Praça Tiradentes and Largo do Rosário. Eighteen people were arrested for using illegal weapons.[37]

On the 12th, there was a new meeting to discuss and approve the bases of the League. The meeting was scheduled for eight in the evening, at the headquarters of the Centro das Classes Operárias on Rua do Espírito Santo, close to Praça Tiradentes.[37] From five in the afternoon, demonstrators began to gather in the São Francisco square. A group of working-class boys playfully started the demonstrations. Mounted on pieces of wood removed from the works, they began to play the events of the day before, simulating the beating of the population by the police cavalry. At eight, everyone headed to the Center. According to Correio da Manhã, around four thousand people from all social classes were present at the meeting, from merchants, workers, military men and students.[39] Lauro Sodré and Barbosa Lima tried to secure the leadership of the popular movement for themselves, giving a political meaning to the revolt. Together with the leaders of the Centro das Classes Operárias, they conspired to overthrow the government through a coup d'état.[40][41] However, the movement took on an increasingly dispersive and spontaneous character.[42]

At the end of the meeting, the crowd marched to Rua do Ouvidor, where they cheered Correio da Manhã, which had its headquarters there, and booed the government newspapers. Next, a group headed to the Catete Palace, passing through Lapa and Glória.[39] On the way, they booed the Minister of War's car, applauded the Army's 9th Cavalry Regiment, booed and shot the Police Brigade commander's car, general Piragibe. The palace was heavily guarded. The crowd turned around and returned to the center. In Glória, Alfredo Varela spoke from the window of his house, advising the protesters to disperse. In Lapa, demonstrators fired again at Piragibe's car, who ordered the troops to charge at them. During the day there were rumors that the Minister of Justice's house had been stoned, which did not happen. However, his house was guarded by the police, as was Oswaldo Cruz's. Soon the Army came into readiness and cavalry and infantry soldiers were sent to guard Catete.[43]

Generalization of conflicts and coup attempt

On Sunday 13th, the conflict became generalized and took on a more violent character. A notice in Correio da Manhã the day before had summoned the people to wait in Praça Tiradentes, where the Ministry of Justice was located, for the results of the commission that would examine the vaccine regulation project. Still during the meeting, at two o'clock in the afternoon, police chief Cardoso de Castro had his car stoned upon arriving at the scene. The police charged into the crowd and the conflict began. Gradually, the disturbances spread to adjacent streets, to Sacramento and Avenida Passos, to Largo de São Francisco, Teatro, Andradas, Assembly, Sete de Setembro, Regente, Camões and São Jorge streets.[43]

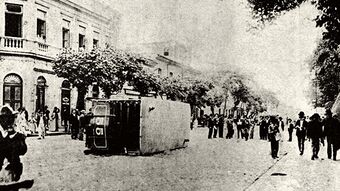

Trams were attacked, overturned and set on fire. Gas burners were broken and electric lighting wires on Avenida Central were cut. Barricades were erected on Avenida Passos and adjacent streets. On Senador Dantas Street, newly planted trees were uprooted. In São Jorge, prostitutes went out into the street and confronted the police, one of them getting injured in the face. There were attacks on police stations and the cavalry barracks on Frei Caneca. There were also attacks on the gasometer and on the tram companies. The conflicts spread, reaching Praça Onze, Tijuca, Gamboa, Saúde, Prainha, Botafogo, Laranjeiras, Catumbi, Rio Comprido and Engenho Novo.[44]

The authorities lost control of the central region and peripheral neighborhoods. In Saúde and Gamboa, the repressive forces were summarily expelled by the residents.[42] At that moment, the speeches and slogans against the vaccine, as well as the attacks on government action symbols in the area of public health, were disappearing. The popular revolt began to be directed towards public services and government representatives, especially against repressive forces.[45] The reaction to mandatory vaccination, interpreted as an attempt to invade private space by public authorities, triggered a broader and deeper protest movement.[46]

The skirmishes continued into the night, with the city partly in darkness as a result of the broken lights. There were shootouts and thieves took advantage to rob passers-by. The owner of a warehouse on Rua do Hospício was arrested, accused of supplying kerosene for demonstrators to burn trams. At the end of the night, Companhia Carris Urbanos already had 22 destroyed trams. The Gas Company informed that more than 100 combustors had been damaged and more than 700 were rendered unusable. At the end of the conflict, several civilians and twelve police officers were injured and there was at least one dead.[44] The Army and Navy began to man buildings and strategic locations. Even when they came forward to disperse the demonstrators, the Army troops were met with great applause by the demonstrators.[47]

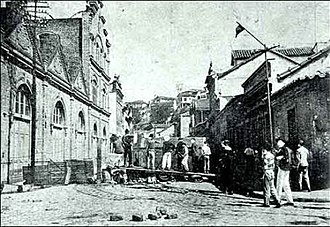

Already at dawn on the 14th, the agitation resumed. Throughout the day, it tended to concentrate in two strongholds, one in the Sacramento district, near Tiradentes square, São Jorge, Sacramento, Regente, Conceição, Senhor dos Passos streets and Passos avenue; and the other in Saúde, extending to Gamboa and Cidade Nova. During the early hours of the morning, two hundred men tried to rob the 3rd Urban Police Station on Rua da Saúde. Nearby, the 2nd Police Station, on Rua Estreita de São Joaquim, was taken over by protesters and soon after abandoned with the arrival of Army troops. In Saúde, there were shootings all day long.[47]

At night, still in Saúde, large groups got together and began to break gas burners, destroy telephone lines and erect barricades. The police force had to be withdrawn and replaced by a contingent of 150 Marines. In Gamboa, Moinho Inglês was attacked, with its gates and glass broken and machinery damaged. On Rua do Regente, there was intense conflict between demonstrators and cavalry, resulting in three deaths. In Prainha, the ferry from Petrópolis was attacked by a group of more than two thousand people, who destroyed the station without disturbing the passengers. There were also attempts to rob gun stores. At night, the Luz Steárica candle factory in São Cristóvão was attacked. The same happened with the gasometers at Mangue, Vila Isabel and Botafogo. On Avenida Central, Public Works wagons were overturned. In Visconde de Itaúna, there was a shootout between civil guards and Army soldiers, commanded by lieutenant Varela, from the 22nd Infantry Battalion. Soldiers arrested and wounded some guards to the cheers of protesters. City Improvements company employees, with a red flag, tried to stop the police assistance wagon and one of them was injured.[48]

During the day, bulletins issued by the chief of police asked "the peaceful population" to return to their homes so that the "disorderly" could be treated with the "maximum rigor". Faced with the generalization of the conflict and by understandings between the Ministers of Justice, the Navy and the Army, the city was divided into three policing zones, with the entire coastline falling to the Navy, the Army to the part north of Avenida Passos, including São Cristóvão and Vila Isabel; and to the police the part south of Avenida Passos. The Army's 38th Infantry Battalion was called from Niterói. Trains left to pick up the 12th Battalion from Lorena, in São Paulo, and the 28th Battalion from São João del-Rei, Minas Gerais.[49]

At the same time, Lauro Sodré and other seditious soldiers were plotting a coup d'état. At first, the coup had been planned for the night of 17 October 1904, the birthday of Lauro Sodré, who would be given the presidency. The denunciation of the conspiracy by the press, however, forced the rebels to postpone their plans.[50] The coup was originally scheduled to take place during the 15 November military parade. It would be up to general Silvestre Travassos, one of the leaders of the plot, to command the troops on parade. He would incite the troops to rebel, gaining the support of the officers already in alliance, imposing the consent of the vacillating ones and disarming the opposing ones. The Vaccine Revolt, however, caused the parade to be suspended.[51] Thus, on the 14th, a meeting was held at the Military Club, attended by Lauro Sodré, Travassos, major Gomes de Castro, deputy Varela, Vicente de Souza and Pinto de Andrade. The Minister of War became aware of the meeting and ordered the president of the club, general Leite de Castro, to dissolve it. On his way to the city center after the meeting, Vicente de Souza was arrested on Rua do Passeio. At night, part of the group that had participated in the meeting went to the Preparatory and Tactical School of Realengo and tried to revolt. The reaction of the commander, general Hermes da Fonseca, thwarted the plan, and major Gomes de Castro and Pinto de Andrade were arrested.[49]

The other group, made up of Lauro Sodré, Travassos and Varela, raised the Military School of Praia Vermelha without major difficulties.[52] Warned, the government concentrated troops from the Army, Navy, Brigade and Firefighters around the Catete Palace and sent a contingent to face the school, which had set off at ten o'clock with about three hundred cadets. The two troops met and exchanged fire on Rua da Passagem, which was completely dark because of the broken lamps. During the skirmish, part of the government troops went over to the side of the rebels, general Travassos fell wounded, Lauro Sodré disappeared and, finally, both sides fled, without knowing what was happening to the other. General Piragibe went to Catete to announce the disbandment of his troops, causing fear in Catete. It was suggested to the president that he retire to a warship anchored in the bay and from there organize the resistance. President Rodrigues Alves turned down the proposal. Soon after, it was reported that the students had also backed out and returned to school. On the morning of the 15th, the cadets surrendered without resistance and were arrest and sent to prison. The rebelling side suffered more casualties, with three killed and several wounded. Among the government troops, thirty-two were wounded.[52]

Last outbreaks of the revolt

The popular protests continued, starting at dawn on the 15th and continuing throughout the day. The main centers of revolt were concentrated in Saúde and Sacramento. In the first, from the top of a trench, in front of Mortona Hill, a red flag was flying. In the vicinity of the second, on Rua Frei Caneca, there was a large trench. Around six hundred workers from the Corcovado and Carioca textile factories and the São Carlos sock factory, all in Jardim Botânico, set up barricades and attacked the 19th Urban Police Station, shouting "die" to the government and the police. A corporal of the guard was killed and the three factories were also attacked and had their windows broken. Attacks continued on police stations, on the gasometer, on weapons stores and even on a funeral home in Frei Caneca. There were disturbances in Méier, Engenho de Dentro, Encantado, Catumbi, São Diogo, Vila Isabel, Andaraí, Matadouro, Aldeia Campista and Laranjeiras.[53] On the same day, army battalions from Minas Gerais and São Paulo arrived. Two battalions of the Public Force of São Paulo also arrived. The government of the state of Rio de Janeiro offered assistance from its police force. In Saúde, the police ordered the Navy to attack the rebels by sea, while families began to leave the neighborhood, fearful of a possible naval bombardment.[53] Rumors circulated that the rebels had cannons and dynamite.[54]

On the 16th, a state of emergency was declared. The repressive operations focused on the Saúde neighborhood, which the government newspaper O Paiz called "the last stronghold of anarchism".[53] In the center of the city, especially in the Sacramento stronghold, skirmishes between the population and the police continued, although with less intensity than in the previous days. The clashes resulted in several injuries. At nightfall, large barricades appeared on Frei Caneca. The actions persisted in Cidade Nova as well. In Jardim Botânico, trams were robbed and the 19th Police Station was abandoned by the police. The Confiança Industrial fabric factory in Vila Isabel was attacked.[54]

Shortly before the final assault on the Saúde neighborhood, to be carried out by land by the 7th Infantry Battalion and by sea by the battleship Deodoro, Horácio José da Silva, known as Prata Preta, was arrested. A stevedore and practitioner of capoeira, Prata Preta was one of the main and most feared leaders of the revolt, leading the protesters on the barricades of the Saúde neighborhood. Before his arrest, he also killed an Army soldier and wounded two policemen. When he was taken to the police station, he was almost lynched by the soldiers, but the chief of police stopped them. He had to be placed in a straitjacket, and even then he continued to insult and threaten the soldiers.[55] Around three in the afternoon, troopa landed near the Moinho Inglês and took a first trench. The battleship Deodoro then approached, while the Army troops advanced along the Mortona hill. By this time, the trenches had been completely abandoned. It was also verified that the dynamites and cannons were nothing more than a decoy. The first ones were, in fact, pieces of wood wrapped in silver paper, suspended by wires around the trenches, while the cannons were nothing more than a public lighting pipe placed on two wagon wheels.[56]

Until the 20th, there were isolated outbreaks of revolt. On the 18th, there was a shooting at a quarry in Catete, which resulted in the death of one civilian and two soldiers, in addition to 80 prisoners. Police chiefs began to sweep the territories under their jurisdiction, arresting suspects and those they considered troublemakers, whether they were related to the revolt or not. On the 19th, the Luz Steárica factory was attacked and several lamps were broken in São Cristóvão, Bonfim and Ponta do Caju.[57] On the 20th, there were a large number of arrests in Gávea. The following day, the number of prisoners on Ilha das Cobras already reached 543. On that day, the Minister of Justice received a complaint that "three dangerous anarchists" had been sent to Rio de Janeiro with the intention of agitating the working class and ordered that measures be taken to prevent disembarkation. As a final act, on the 23rd, the police raided Favela Hill, mobilizing 180 soldiers. The huts on the hill were swept away. On the way back, the troops searched tenement houses and arrested several people. By then, there were more than seven hundred prisoners on the island.[58]

Aftermath

Despite its relatively swift downfall, the revolt convinced the mayor and his cabinet to abandon the forced-vaccination program for the time being. This concession was ultimately demonstrated to have been quite superficial, however, as the policy was re-instated several years later. Whatever popular frustrations or progressive ideals that the anti-vaccination movement and its allies might have expressed were thoroughly swept aside with the re-imposition of lawful authority, as the processes of unequal economic development and gentrification continued to accelerate following the uprising. Trade unions were severely marginalized, increasingly dismissed by political elites and middle-class professionals as an unsophisticated reaction against modernization. Moreover, the economic power of these native-born Brazilian workers was further diminished as increasingly large quantities of foreign laborers arrived in Rio de Janeiro on an annual basis. Senator Lauro Sodré subsequently enjoyed a figurehead status among Rodrigues Alves' opposition.[31] The military uprising, in turn, had repercussions in Bahia, where a garrison rose up and was promptly neutralized. In Recife, the agitation of the press favorable to the revolt provoked some innocuous marches through the city. In Rio de Janeiro, the Military School of Praia Vermelha was closed and its students exiled to Brazil's remote border regions and then dismissed from the Army.[59]

Among the civilians, only four were prosecuted – Alfredo Varela, Vicente de Souza, Pinto de Andrade and Arthur Rodrigues.[60] In all, 945 people were arrested. Of these, 461 had a criminal record and were deported. The remaining 481 were released. Seven foreigners were deported.[61] The poor rank-and-file of the revolt were much less fortunate, as many hundreds were deported to both the offshore detention facility of Ilha das Cobras and the frontier region of Acre, although their participation was not always proven.[62] Those transported to this distant territory were shipped aboard "coastal packet-boats", where it was claimed that they faced egregious conditions.[31] In addition to the fierce repression launched by the government, the population of Rio de Janeiro would have to endure a smallpox epidemic in 1908, in which almost 6,400 people died.[63]

In fiction

- Scliar, Moacyr (1992) (in pt). Sonhos Tropicais. Companhia das Letras. ISBN 85-7164-249-4.

- Sonhos Tropicais, a 2001 film adaptation of cited Scliar's book. Synopsis: in english and in Portuguese

See also

- Vaccine controversy

- Revolutions of Brazil

- Vaccine hesitancy

Notes

- ↑ The government of Campos Sales was marked by a policy to fight inflation that was characterized by the reduction of the circulating currency, the drastic containment of government expending and the increase of taxes, especially through the gold tariff on imported products. Sales' Minister of Finance, Joaquim Murtinho, managed to raise the exchange rate and produce a budget surplus. Although domestic prices had dropped significantly, there had also been a drop in job offers and an increase in taxes, generating great dissatisfaction among the population.[7]

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Benchimol 2003, p. 244.

- ↑ Benchimol 2003, p. 243.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 40.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 39.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sevcenko 1999, p. 33.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 30.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 92.

- ↑ Benchimol 2003, p. 255.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 33-34.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 31.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Sevcenko 1999, p. 32.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 35.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 35-36.

- ↑ Teixeira 2020, pp. 144-148.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 95.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Carvalho 2003, p. 93.

- ↑ Carvalho 2003, p. 94.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 44.

- ↑ Benchimol 2003, p. 259.

- ↑ Benchimol 2003, p. 263.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Sevcenko 1999, p. 38.

- ↑ Benchimol 2003, p. 271.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 94.

- ↑ Benchimol 2003, p. 272.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Sevcenko 1999, p. 6.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 96.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 6-7.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 97.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 98.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 100.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Needel 1987, pp. 244–258.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 130-131.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 131.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 99.

- ↑ Benchimol 2003, p. 273.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 10.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Carvalho 2005, p. 101.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 11.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 102.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 12.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 123.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Sevcenko 1999, p. 13.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 103.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 104.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 133.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 134.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 105.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 106.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 107.

- ↑ Benchimol 2003, p. 274.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 20.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 108.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Carvalho 2005, p. 109.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Carvalho 2005, p. 110.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 110-111.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 111.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 112.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 113.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 25.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 114.

- ↑ Carvalho 2005, p. 117.

- ↑ Sevcenko 1999, p. 52.

- ↑ Benchimol 2003, p. 277.

Bibliography

- Arretche, M.T.S. (2007) (in pt). Políticas públicas no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz.

- Benchimol, Jaime (2003). "Reforma urbana e Revolta da Vacina na cidade do Rio de Janeiro" (in pt). Brasil Republicano. 1. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

- Carvalho, José Murilo (2005) (in pt). Os Bestializados. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- Hochman, Gilberto (2009). "Priority, Invisibility and Eradication: The History of Smallpox and the Brazilian Public Health Agenda". Medical History 53 (2): 229–52. doi:10.1017/S002572730000020X. PMID 19367347.

- Needell, Jeffrey D. (May 1987). "The Revolta Contra Vacina of 1904: The Revolt against "Modernization" in Belle-Époque Rio de Janeiro". The Hispanic American Historical Review 67 (2): 244–58. doi:10.2307/2515023. PMID 11619656.

- Teixeira, Suelem (2020) (in pt). O Rio de Janeiro pelo Brasil: a grande reforma urbana nos jornais do país (1903-1906). Rio de Janeiro: Unirio.

- Sevcenko, Nicolau (1999) (in pt). A Revolta da Vacina. Porto Alegre: Scipione.

|