Black bag operation

Black bag operations or black bag jobs are covert or clandestine entries into structures to obtain information for human intelligence operations.[1]

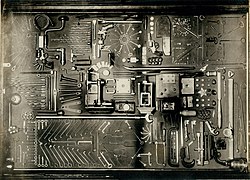

Some of the tactics, techniques, and procedures associated with black bag operations are lock picking, safe cracking, key impressions, fingerprinting, photography, electronic surveillance (including audio and video surveillance), mail manipulation (flaps and seals), and forgery. The term "black bag" refers to the small bags in which burglars stereotypically carry their tools.

History

In black bag operations, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents entered offices of targeted individuals and organizations, and photographed information found in their records. This practice was used by the FBI from 1942 through the 1960s. In July 1966, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover allegedly ordered the practice discontinued.[2] President Nixon in 1970 proposed the Huston Plan to reintroduce black bag jobs, but Hoover opposed this, and approval was revoked five days after it was approved.[3]

Prior to it being discontinued, there had been over two hundred instances of black bag jobs organized by the FBI, for purposes other than installing microphones (as well as over 500 warrant-less microphone installations). These were approved in writing by Hoover as well as by Hoover's deputy Clyde Tolson, with most records being destroyed after the job was complete.[4] Agents were trained in lock studies or electronic surveillance that performed the jobs. In many cases, lock-picking was not required and a key could be accessed from a landlord, hotel manager, or a neighbor.[5]

However, William C. Sullivan and W. Mark Felt subsequently testified that Hoover and acting FBI director L. Patrick Gray III authorized "black bag" jobs against the Weather Underground from 1970 to 1973.[6][7]

The use of "black bag jobs" by the FBI was declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court on 19 June 1972 in the Plamondon case, United States v. U.S. District Court, 407 U.S. 297. The FBI still carries out numerous "black bag" entry-and-search missions, in which the search is covert and the target of the investigation is not informed that the search took place. If the investigation involves a criminal matter, a judicial warrant is required; in national security cases the operation must be approved by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.[8]

In 1947, after American spy Elizabeth Bentley had defected from the Soviet underground and had started talking to the FBI, the FBI broke into her Brooklyn hotel to do a "black bag job" to verify her own background – and to look for anything that would invoke suspicion. "They found nothing out of the ordinary."[9] Bentley had learned how to dodge such intrusions from her earliest days in the underground:

She learned how to determine if enemy agents had discovered secret documents in her possession. "If I had to leave the apartment, I was careful to put them in my black trunk and tie a thin black thread around it so that I would know if they had been tampered with in my absence."[10]

The CIA has used black bag operations to steal cryptography and other secrets from foreign government offices outside the United States. The practice (by preceding U.S. intelligence organizations) dates back at least as far as 1916.[11]

Black bag operations in popular culture

- Sam Fisher (Splinter Cell)

- Sombra (Overwatch)

- The Doorbell Rang

See also

- Black operation

- COINTELPRO

- Elizabeth Bentley

- Parallel construction

References

General references

- Wright, Peter, Spy Catcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer. Penguin USA, 1987. ISBN 0-670-82055-5.

Inline citations

- ↑ "Tallinn government surveillance cameras reveal black bag operation". Intelnews. 16 December 2008. http://intelnews.org/2008/12/16/04-11/.

- ↑ "Freedom of Information/Privacy Act" (in en-US). Federal Bureau of Investigation. https://www.fbi.gov/services/freedom-of-informationprivacy-act.

- ↑ Select 1976, p. 9.

- ↑ Select 1976, p. 1.

- ↑ Select 1976, p. 4.

- ↑ Robinson, Timothy S. (13 July 1978). "Testimony Cites Hoover Approval of Black-Bag Jobs" (in en-US). The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1978/07/13/testimony-cites-hoover-approval-of-black-bag-jobs/6aada29d-5984-4ed8-adae-4f730cd2584e/.

- ↑ Kiernan, Laura A. (16 October 1980). "FBI 'Bag Jobs' Allowable, Court Told" (in en-US). The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1980/10/16/fbi-bag-jobs-allowable-court-told/293e28c3-4551-41f7-b863-bad9d7707926/.

- ↑ Rood, Justin (15 June 2007). "FBI to Boost 'Black Bag' Search Ops". ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/blogs/headlines/2007/06/as_part_of_its_/.

- ↑ Kessler, Lauren (13 October 2009). Clever Girl: Elizabeth Bentley, the Spy Who Ushered in the McCarthy Era. HarperCollins. p. 130. ISBN 9780061740473. https://books.google.com/books?id=HhsuY7ktPnYC. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ↑ Olmsted, Kathryn J. (3 November 2003). Red Spy Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth Bentley. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9780807862179. https://books.google.com/books?id=XVduAwAAQBAJ. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ↑ "The CIA Code Thief Who Came in from the Cold". http://www.matthewaid.com/post/32043919336/the-cia-code-thief-who-came-in-from-the-cold.

Bibliography

- Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations (23 April 1976) (pdf). Supplementary Detailed Staff Reports on Intelligence Activities and the Rights of Americans (Report). U.S. Senate. https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=479840.

External links

- "11 Terms Used by Spies". HowStuffWorks.