Boundary (topology)

In topology and mathematics in general, the boundary of a subset S of a topological space X is the set of points in the closure of S not belonging to the interior of S. An element of the boundary of S is called a boundary point of S. The term boundary operation refers to finding or taking the boundary of a set. Notations used for boundary of a set S include and .

Some authors (for example Willard, in General Topology) use the term frontier instead of boundary in an attempt to avoid confusion with a different definition used in algebraic topology and the theory of manifolds. Despite widespread acceptance of the meaning of the terms boundary and frontier, they have sometimes been used to refer to other sets. For example, Metric Spaces by E. T. Copson uses the term boundary to refer to Hausdorff's border, which is defined as the intersection of a set with its boundary.[1] Hausdorff also introduced the term residue, which is defined as the intersection of a set with the closure of the border of its complement.[2]

Definitions

There are several equivalent definitions for the boundary of a subset of a topological space which will be denoted by or simply if is understood:

- It is the closure of minus the interior of in : where denotes the closure of in and denotes the topological interior of in

- It is the intersection of the closure of with the closure of its complement:

- It is the set of points such that every neighborhood of contains at least one point of and at least one point not of :

A boundary point of a set is any element of that set's boundary. The boundary defined above is sometimes called the set's topological boundary to distinguish it from other similarly named notions such as the boundary of a manifold with boundary or the boundary of a manifold with corners, to name just a few examples.

A connected component of the boundary of S is called a boundary component of S.

Properties

The closure of a set equals the union of the set with its boundary: where denotes the closure of in A set is closed if and only if it contains its boundary, and open if and only if it is disjoint from its boundary. The boundary of a set is closed;[3] this follows from the formula which expresses as the intersection of two closed subsets of

("Trichotomy") Given any subset each point of lies in exactly one of the three sets and Said differently, and these three sets are pairwise disjoint. Consequently, if these set are not empty[note 1] then they form a partition of

A point is a boundary point of a set if and only if every neighborhood of contains at least one point in the set and at least one point not in the set. The boundary of the interior of a set as well as the boundary of the closure of a set are both contained in the boundary of the set.

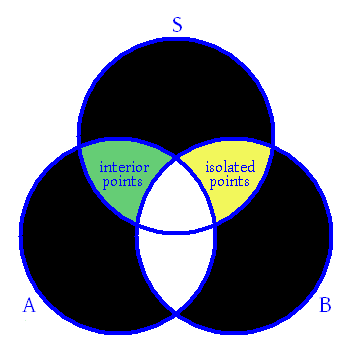

Conceptual Venn diagram showing the relationships among different points of a subset of = set of limit points of set of boundary points of area shaded green = set of interior points of area shaded yellow = set of isolated points of areas shaded black = empty sets. Every point of is either an interior point or a boundary point. Also, every point of is either an accumulation point or an isolated point. Likewise, every boundary point of is either an accumulation point or an isolated point. Isolated points are always boundary points.

Examples

Characterizations and general examples

A set and its complement have the same boundary:

A set is a dense open subset of if and only if

The interior of the boundary of a closed set is empty.[proof 1] Consequently, the interior of the boundary of the closure of a set is empty. The interior of the boundary of an open set is also empty.[proof 2] Consequently, the interior of the boundary of the interior of a set is empty. In particular, if is a closed or open subset of then there does not exist any nonempty subset such that is open in This fact is important for the definition and use of nowhere dense subsets, meager subsets, and Baire spaces.

A set is the boundary of some open set if and only if it is closed and nowhere dense. The boundary of a set is empty if and only if the set is both closed and open (that is, a clopen set).

Concrete examples

Consider the real line with the usual topology (that is, the topology whose basis sets are open intervals) and the subset of rational numbers (whose topological interior in is empty). Then

These last two examples illustrate the fact that the boundary of a dense set with empty interior is its closure. They also show that it is possible for the boundary of a subset to contain a non-empty open subset of ; that is, for the interior of in to be non-empty. However, a closed subset's boundary always has an empty interior.

In the space of rational numbers with the usual topology (the subspace topology of ), the boundary of where is irrational, is empty.

The boundary of a set is a topological notion and may change if one changes the topology. For example, given the usual topology on the boundary of a closed disk is the disk's surrounding circle: If the disk is viewed as a set in with its own usual topology, that is, then the boundary of the disk is the disk itself: If the disk is viewed as its own topological space (with the subspace topology of ), then the boundary of the disk is empty.

Boundary of an open ball vs. its surrounding sphere

This example demonstrates that the topological boundary of an open ball of radius is not necessarily equal to the corresponding sphere of radius (centered at the same point); it also shows that the closure of an open ball of radius is not necessarily equal to the closed ball of radius (again centered at the same point). Denote the usual Euclidean metric on by which induces on the usual Euclidean topology. Let denote the union of the -axis with the unit circle centered at the origin ; that is, which is a topological subspace of whose topology is equal to that induced by the (restriction of) the metric In particular, the sets and are all closed subsets of and thus also closed subsets of its subspace Henceforth, unless it clearly indicated otherwise, every open ball, closed ball, and sphere should be assumed to be centered at the origin and moreover, only the metric space will be considered (and not its superspace ); this being a path-connected and locally path-connected complete metric space.

Denote the open ball of radius in by so that when then is the open sub-interval of the -axis strictly between and The unit sphere in ("unit" meaning that its radius is ) is while the closed unit ball in is the union of the open unit ball and the unit sphere centered at this same point:

However, the topological boundary and topological closure in of the open unit ball are: In particular, the open unit ball's topological boundary is a proper subset of the unit sphere in And the open unit ball's topological closure is a proper subset of the closed unit ball in The point for instance, cannot belong to because there does not exist a sequence in that converges to it; the same reasoning generalizes to also explain why no point in outside of the closed sub-interval belongs to Because the topological boundary of the set is always a subset of 's closure, it follows that must also be a subset of

In any metric space the topological boundary in of an open ball of radius centered at a point is always a subset of the sphere of radius centered at that same point ; that is, always holds.

Moreover, the unit sphere in contains which is an open subset of [proof 3] This shows, in particular, that the unit sphere in contains a non-empty open subset of

Boundary of a boundary

For any set where denotes the superset with equality holding if and only if the boundary of has no interior points, which will be the case for example if is either closed or open. Since the boundary of a set is closed, for any set The boundary operator thus satisfies a weakened kind of idempotence.

In discussing boundaries of manifolds or simplexes and their simplicial complexes, one often meets the assertion that the boundary of the boundary is always empty. Indeed, the construction of the singular homology rests critically on this fact. The explanation for the apparent incongruity is that the topological boundary (the subject of this article) is a slightly different concept from the boundary of a manifold or of a simplicial complex. For example, the boundary of an open disk viewed as a manifold is empty, as is its topological boundary viewed as a subset of itself, while its topological boundary viewed as a subset of the real plane is the circle surrounding the disk. Conversely, the boundary of a closed disk viewed as a manifold is the bounding circle, as is its topological boundary viewed as a subset of the real plane, while its topological boundary viewed as a subset of itself is empty. In particular, the topological boundary depends on the ambient space, while the boundary of a manifold is invariant.

See also

- See the discussion of boundary in topological manifold for more details.

- Bounding point – Mathematical concept related to subsets of vector spaces

- Closure (topology) – All points and limit points in a subset of a topological space

- Exterior (topology) – Largest open set disjoint from some given set

- Interior (topology) – Largest open subset of some given set

- Nowhere dense set – Mathematical set whose closure has empty interior

- Lebesgue's density theorem, for measure-theoretic characterization and properties of boundary

- Surface (topology) – Two-dimensional manifold

Notes

- ↑ Let be a closed subset of so that and thus also If is an open subset of such that then (because ) so that (because by definition, is the largest open subset of contained in ). But implies that Thus is simultaneously a subset of and disjoint from which is only possible if Q.E.D.

- ↑ Let be an open subset of so that Let so that which implies that If then pick so that Because is an open neighborhood of in and the definition of the topological closure implies that which is a contradiction. Alternatively, if is open in then is closed in so that by using the general formula and the fact that the interior of the boundary of a closed set (such as ) is empty, it follows that

- ↑ The -axis is closed in because it is a product of two closed subsets of Consequently, is an open subset of Because has the subspace topology induced by the intersection is an open subset of

Citations

- ↑ Hausdorff, Felix (1914). Grundzüge der Mengenlehre. Leipzig: Veit. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-8284-0061-9. https://archive.org/details/grundzgedermen00hausuoft. Reprinted by Chelsea in 1949.

- ↑ Hausdorff, Felix (1914). Grundzüge der Mengenlehre. Leipzig: Veit. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-8284-0061-9. https://archive.org/details/grundzgedermen00hausuoft. Reprinted by Chelsea in 1949.

- ↑ Mendelson, Bert (1990). Introduction to Topology (Third ed.). Dover. p. 86. ISBN 0-486-66352-3. "Corollary 4.15 For each subset is closed."

References

- Munkres, J. R. (2000). Topology. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-181629-2.

- Willard, S. (1970). General Topology. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-08707-3. https://archive.org/details/generaltopology00will_0.

- van den Dries, L. (1998). Tame Topology. ISBN 978-0521598385.

|