Chain (algebraic topology)

In algebraic topology, a k-chain is a formal linear combination of the k-cells in a cell complex. In simplicial complexes (respectively, cubical complexes), k-chains are combinations of k-simplices (respectively, k-cubes),[1][2][3] but not necessarily connected. Chains are used in homology; the elements of a homology group are equivalence classes of chains.

Definition

For a simplicial complex , the group of -chains of is given by:

where are singular -simplices of . that any element in not necessary to be a connected simplicial complex.

Integration on chains

Integration is defined on chains by taking the linear combination of integrals over the simplices in the chain with coefficients (which are typically integers). The set of all k-chains forms a group and the sequence of these groups is called a chain complex.

Boundary operator on chains

The boundary of a chain is the linear combination of boundaries of the simplices in the chain. The boundary of a k-chain is a (k−1)-chain. Note that the boundary of a simplex is not a simplex, but a chain with coefficients 1 or −1 – thus chains are the closure of simplices under the boundary operator.

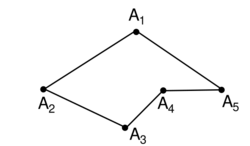

Example 1: The boundary of a path is the formal difference of its endpoints: it is a telescoping sum. To illustrate, if the 1-chain is a path from point to point , where , and are its constituent 1-simplices, then

Example 2: The boundary of the triangle is a formal sum of its edges with signs arranged to make the traversal of the boundary counterclockwise.

A chain is called a cycle when its boundary is zero. A chain that is the boundary of another chain is called a boundary. Boundaries are cycles, so chains form a chain complex, whose homology groups (cycles modulo boundaries) are called simplicial homology groups.

Example 3: The plane punctured at the origin has nontrivial 1-homology group since the unit circle is a cycle, but not a boundary.

In differential geometry, the duality between the boundary operator on chains and the exterior derivative is expressed by the general Stokes' theorem.

References

- ↑ Hatcher, Allen (2002). Algebraic Topology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79540-0. http://www.math.cornell.edu/~hatcher/AT/ATpage.html.

- ↑ Lee, John M. (2011). Introduction to topological manifolds (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1441979391. OCLC 697506452.

- ↑ Kaczynski, Tomasz; Mischaikow, Konstantin; Mrozek, Marian (2004). Computational homology. Applied Mathematical Sciences. 157. New York: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/b97315. ISBN 0-387-40853-3.

|