Chemistry:Caylus vase

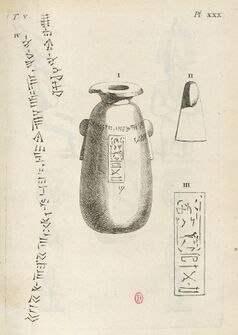

The Caylus vase is an Egyptian alabaster jar dedicated in the name of the Achaemenid king Xerxes I (c.518–465 BCE) in Egyptian hieroglyphs and Old Persian cuneiform, which in 1823 played an important role in the modern decipherment of cuneiform and the decipherment of ancient Egyptian scripts.

Beyond its historical value as a dynastic artifact of Achaemenid Egypt, its quadrilingual inscription was also the key element in confirming the decipherment of Old Persian cuneiform by Grotefend, through the reading of the hieroglyphic part by Champollion in 1823. It also confirmed the antiquity of phonetical hieroglyphs before the time of Alexander the Great, thus corroborating the phonetical decipherment of the names of ancient Egyptian pharaohs. The vase was named after Anne Claude de Tubières, count of Caylus, an early French collector, who had acquired the vase in the 18th century, between 1752 and 1765.[2] It is now located in the Cabinet des Médailles, Paris (inv. 65.4695).[2]

Description

The vase is made in alabaster, with a height of 29.2 cm, and a diameter of 16 cm.[2] Several similar vases, probably made in Egypt in the name of Xerxes I, have since been found, such as the Jar of Xerxes I, found in the ruins of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus.

The vase has a quadrilingual inscription, in Old Persian, Babylonian, and Elamite cuneiforms, and in Egyptian hieroglyphs.[2] All three inscriptions have the same meaning "Xerxes : The Great King". The Old Persian cuneiform inscription in particular, comes first in the series of languages, and reads:

𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 𐏐 𐏋 𐏐 𐎺𐏀𐎼𐎣

( Xšayāršā : XŠ : vazraka)

"Xerxes : The Great King."

The line in Egyptian hieroglyph has the same meaning, and critically uses the cartouche for the name of Xerxes.

The vase remained undeciphered for a long time after its acquisition by Caylus, but Caylus had already announced in 1762, in his publication of the vase, that the inscription combined the Egyptian script with the cuneiform script found in the monuments of Persepolis.[4] Upon Caylus's death in 1765, the vase was given to the Cabinet des Médailles collection in Paris.[5][2]

Contribution to the decipherment of cuneiform

Grotefend hypothesis (1802-1815)

The early attempts at deciphering Old Persian cuneiform were made by Münter and Grotefend by guesswork only, using Achaemenid cuneiform inscriptions found in Persepolis. In 1802, Friedrich Münter realized that recurring groups of characters must be the word for "king" (𐎧𐏁𐎠𐎹𐎰𐎡𐎹, now known to be pronounced xšāyaθiya[check spelling]). Georg Friedrich Grotefend extended this work by realizing a king's name is often followed by "great king, king of kings" and the name of the king's father.[7][8] This, related to the known chronology of the Achaemenid and the relative sizes of each royal names, allowed Grotefend to figure out the cuneiform characters that are part of Darius, Darius's father Hystaspes, and Darius's son Xerxes. Grotefend's contribution to Old Persian is unique in that he did not have comparisons between Old Persian and known languages, as opposed to the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Rosetta Stone. All his decipherments were done by comparing the texts with known history.[8]

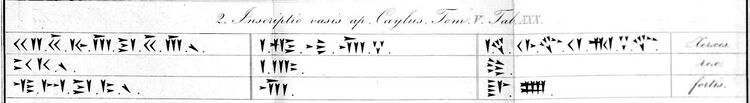

Grotefend presented his deductions in 1802, but they were dismissed by the Academic community, and denied publication.[8] Grotefend had also proposed a reading of the cuneiform inscriptions on the Caylus vase since 1805, translating it quite accurately as "Xerxes rex fortis" ("Xerxes, the Strong King", although it is actually "Xerxes, the Great King").[9][10][11][12] He was the first to make this suggestion.[10]

Champollion decipherment and confirmation (1823)

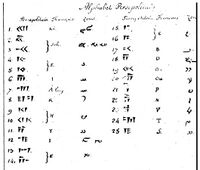

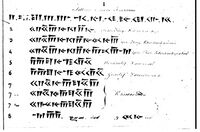

It was only in 1823 that Grotefend's discovery was confirmed, when Jean-François Champollion, who had just deciphered hieroglyphs, had the idea to test his new decipherement technique on the quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription on the famous "Caylus vase" in the Cabinet des Médailles.[15][1][16] The Egyptian inscription on the vase turned out to be in the name of King Xerxes I, and the orientalist Antoine-Jean Saint-Martin, who accompanied Champollion, was able to confirm that the corresponding words in the cuneiform script (𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 𐏐 𐏋 𐏐 𐎺𐏀𐎼𐎣, Xšayāršā : XŠ : vazraka, "Xerxes : The Great King") were indeed using the words which Grotefend had identified as meaning "king" and "Xerxes" through guesswork.[15][1][16] The findings were published by A.J. Saint-Martin in Extrait d'un mémoire relatif aux antiques inscriptions de Persépolis lu à l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres.[17][18] Saint-Martin attempted to define an Old Persian cuneiform alphabet, of which 10 letters were correct, on a total of 39 signs he had identified.[19]

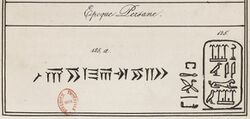

Caylus vase, transcription by Saint-Martin in 1823.[15]

Persepolitan alphabet by Saint-Martin, 1823.[15]

Old Persian cuneiform translation by Saint-Martin, 1823.[15]

The Caylus vase was key in confirming the validity of the first decipherments of Old Persian cuneiform, and opened the door to the subsequent decipherment of all cuneiform inscriptions as far back as the oldest Akkadian and Sumerian inscriptions.[8] In effect the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs was decisive in confirming the first steps of the decipherment of the cuneiform script.[16]

More advances were made on Grotefend's work and by 1847, most of the symbols were correctly identified. The decipherment of the Old Persian Cuneiform script was at the beginning of the decipherment of all the other cuneiform scripts, as various multi-lingual inscriptions between the various cuneiform scripts were obtained form archaeological discoveries.[8] The decipherment of Old Persian was notably useful to the decipherment of Elamite, Babylonian and ultimately Akkadian (predecessor of Babylonian), through the multilingual Behistun Inscription.

Confirmation of the antiquity of phonetical hieroglyphs

Champollion had been confronted to the doubts of various scholars regarding the existence of phonetical hieroglyphs before the time of the Greeks and the Romans in Egypt, especially since Champollion had only proved his phonetic system on the basis of the names of Greek and Roman rulers found in hieroglyphs on Egyptian monuments.[21][22] Until his decipherment of the Caylus vase, he hadn't found any foreign names earlier than Alexander the Great that were transliterated through alphabetic hieroglyphs, which led to suspicions that alphabetic hieroglyphs were invented at the time of the Greeks and Romans, and fostered doubts whether these phonetical hieroglyphs could be applied to decipher the names of ancient Egyptian Pharaos.[21][22] For the first time, here was a foreign name ("Xerxes the Great") transcribed phonetically with Egyptian hieroglyphs, already 150 years before Alexander the Great, thereby essentially proving Champollion's thesis.[21] In his Précis du système hiéroglyphique published in 1824, Champollion wrote of this discovery: "It has thus been proved that Egyptian hieroglyphs included phonetic signs, at least since 460 BCE".[23]

Confirmation of Egyptian chronology

Until the decipherment of the Caylus phase by Champollion, many uncertainties and competing theories had remained regarding the chronology of Ancient Egyptian history and monuments, due to the lack of positive datation. The decipherment of the Caylus vase confirmed the existence of Ancient Egyptian inscriptions well before the time of Alexander the Great, and opened up the establishment of the chronology of Egyptian rulers, based on the alphabetical reading of their names.[24]

Similar jars

A few similar alabaster jars exist, from the time of Darius I to Xerxes, and to some later Achaemenid rulers, especially Artaxerxes I.[25]

The Jar of Xerxes I from the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, at time of discovery in 1857.

Another jar of Xerxes I, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[26]

The same jar in black and white photography.[27]

Jar of Xerxes I, year 2. Louvre Museum.[28]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Pages 10-14, note 1 on page 13 Sayce, Archibald Henry (2019) (in en). The Archaeology of the Cuneiform Inscriptions. Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–14. ISBN 978-1-108-08239-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=DTyaDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA12.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "vase (inv.65.4695) - inv.65.4695 , BnF" (in fr). http://medaillesetantiques.bnf.fr/ws/catalogue/app/collection/record/ark:/12148/c33gbts1b.

- ↑ Recueil d'antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques, romaines et gauloises : Tome cinquième. Bibliothèque de l'Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art, collections Jacques Doucet. 1762. p. Plaque XXX. https://bibliotheque-numerique.inha.fr/collection/item/5664-recueil-d-antiquites-egyptiennes-etrusques-grecques-romaines-et-gauloises-tome-5.

- ↑ Caylus (1762). Recueil d'antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques, romaines et gauloises. Tome 5. p. 80. https://bibliotheque-numerique.inha.fr/viewer/5664/?offset=#page=114.

- ↑ Hasselbach-Andee, Rebecca (2020) (in en). A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Languages. John Wiley & Sons. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-119-19389-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Hd7SDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA10.

- ↑ "Vase bilingue au nom de Xerxès (inv.65.4695)" (in fr). https://medaillesetantiques.bnf.fr/ws/catalogue/app/collection/record/ark:/12148/c33gbts1b.

- ↑ Kent, R. G.: "Old Persian: Grammar Texts Lexicon", page 10. American Oriental Society, 1950.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Sayce, Archibald Henry (2019) (in en). The Archaeology of the Cuneiform Inscriptions. Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–14. ISBN 978-1-108-08239-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=DTyaDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA12.

- ↑ Heeren, A. H. L. (Arnold Hermann Ludwig) (1857). Vol. 2: Historical researches into the politics, intercourse, and trade of the principal nations of antiquity. / By A.H.L. Heeren. Tr. from the German. H.G. Bohn. p. 318, plate. https://archive.org/details/vol2historicalre00heer/page/n327/mode/2up.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Pauthier, Guillaume (1842) (in fr). Sinico-aegyptica: essai sur l'origine et la formation similaire des écritures figuratives chinoise et égyptienne.... Firmin Didot frères. pp. 123–124. https://books.google.com/books?id=yp3LAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA123.

- ↑ Heeren, Arnold Hermann Ludwig (1815) (in de). Ideen über die Politik, den Verkehr und den Handel der vornehmsten Völker der alten Welt. Bey Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. p. 565, plates. https://books.google.com/books?id=JQ0PAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA565.

- ↑ Heeren, A. H. L. (Arnold Hermann Ludwig) (1857). Vol. 2: Historical researches into the politics, intercourse, and trade of the principal nations of antiquity. / By A.H.L. Heeren. Tr. from the German. H.G. Bohn. p. 324. https://archive.org/details/vol2historicalre00heer/page/324/mode/2up/search/caylus.

- ↑ Heeren, Arnold Hermann Ludwig (1815) (in de). Ideen über die Politik, den Verkehr und den Handel der vornehmsten Völker der alten Welt. Bey Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. p. 562. https://books.google.com/books?id=JQ0PAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA562.

- ↑ (in fr) Recueil des publications de la Société Havraise d'Études Diverses. Société Havraise d'Etudes Diverses. 1869. p. 423. https://books.google.com/books?id=XcRJAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA423.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Saint-Martin, Antoine-Jean (January 1823). "Extrait d'un mémoire relatif aux antiques inscriptions de Persépolis lu à l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres" (in FR). Journal asiatique (Société asiatique (France)): 86. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k931015/f89.item.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 (in fr) Bulletin des sciences historiques, antiquités, philologie. Treuttel et Würtz. 1825. p. 135. https://books.google.com/books?id=l302AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA135.

- ↑ Saint-Martin, Antoine-Jean (January 1823). "Extrait d'un mémoire relatif aux antiques inscriptions de Persépolis lu à l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres" (in FR). Journal asiatique (Société asiatique (France)): 65-90. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k931015/f64.item.

- ↑ In Journal asiatique II, 1823, PI. II, pp. 65—90 AAGE PALLIS, SVEND. EARLY EXPLORATION IN MESOPOTAMIA. p. 36. http://www.royalacademy.dk/Publications/High/613_Pallis,%20Svend%20Aage.pdf.

- ↑ (in en) The Persian Cuneiform Inscription at Behistun: Decyphered and Tr.; with a Memoir on Persian Cuneiform Inscriptions in General, and on that of Behistun in Particular. J.W. Parker. 1846. p. 6. https://books.google.com/books?id=8spIAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA6.

- ↑ Champollion, Jean-François (1790-1832) Auteur du texte (1824) (in EN). Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, ou Recherches sur les éléments premiers de cette écriture sacrée, sur leurs diverses combinaisons, et sur les rapports de ce système avec les autres méthodes graphiques égyptiennes. Planches / . Par Champollion le jeune.... https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k10475324/f35.item..

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 (in fr) Revue archéologique. Leleux. 1844. p. 444. https://books.google.com/books?id=_CYGAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA444.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Champollion, Jean-François (1790-1832) Auteur du texte (1828) (in EN). Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, ou Recherches sur les éléments premiers de cette écriture sacrée, sur leurs diverses combinaisons, et sur les rapports de ce système avec les autres méthodes graphiques égyptiennes , par M. Champollion le jeune. Seconde édition... augmentée de la lettre à M. Dacier relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques employés par les Égyptiens sur leurs monumens de l'époque grecque et de l'époque romaine,.... pp. 225–233. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k117252f/f266.item.r=xerxes.

- ↑ Champollion, Jean-François (1790-1832) Auteur du texte (1828) (in EN). Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, ou Recherches sur les éléments premiers de cette écriture sacrée, sur leurs diverses combinaisons, et sur les rapports de ce système avec les autres méthodes graphiques égyptiennes , par M. Champollion le jeune. Seconde édition... augmentée de la lettre à M. Dacier relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques employés par les Égyptiens sur leurs monumens de l'époque grecque et de l'époque romaine,.... pp. 231–233. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k117252f/f266.item.r=xerxes.

- ↑ Champollion, Jean-François (1790-1832) Auteur du texte (1828) (in EN). Précis du système hiéroglyphique des anciens Égyptiens, ou Recherches sur les éléments premiers de cette écriture sacrée, sur leurs diverses combinaisons, et sur les rapports de ce système avec les autres méthodes graphiques égyptiennes , par M. Champollion le jeune. Seconde édition... augmentée de la lettre à M. Dacier relative à l'alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques employés par les Égyptiens sur leurs monumens de l'époque grecque et de l'époque romaine,.... pp. 225-240. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k117252f/f260.item.r=xerxes.

- ↑ (in en) Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. 1924. p. 282-283. ISBN 9780521228046. https://books.google.com/books?id=nNDpPqeDjo0C&pg=PA283.

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/543949.

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/543949.

- ↑ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". 486. http://cartelfr.louvre.fr/cartelfr/visite?srv=car_not&idNotice=12902.

- ↑ (in fr) Revue archéologique. Leleux. 1844. p. 444-450. https://books.google.com/books?id=_CYGAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA444.

- ↑ The vase is now in the Reza-Abbasi Museum in Teheran (inv. 53). image inscription

|