Chemistry:Glenbrook Tunnel (1892)

Entrance to the 1892 Glenbrook Tunnel | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) |

|

| Line | Main Western Line (since deviated) |

| Location | Glenbrook |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 33°45′54″S 150°37′56″E / 33.7651°S 150.6323°E |

| Status | Abandoned |

| System | Heavy rail |

| Start | Tunnel Gully Reserve (east) [ ⚑ ] 33°46′04″S 150°38′06″E / 33.76777°S 150.63509°E |

| End | Mushroom Farm (west) [ ⚑ ] 33°45′49″S 150°37′48″E / 33.763581°S 150.629925°E |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | April 1891 |

| Opened | December 1892[1] |

| Closed | 1913 |

| Owner |

|

| Character | Passenger |

| Technical | |

| Design engineer | NSW Government Railways |

| Length | 634 metres; 693 yards (31.5 chains)[2] |

| No. of tracks | Single (since removed) |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Grade | 1:33 |

| Official name |

|

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Designated | 5 August 2011 |

| Reference no. | 1861 |

| Type | Military Tunnel |

| Category | Defence |

| Builders | Department of Railways |

The Glenbrook Tunnel is a heritage-listed single-track former railway tunnel and mustard gas storage facility and previously a mushroom farm located on the former Main Western Line (since deviated) at the Great Western Highway, Glenbrook, in the City of Blue Mountains local government area of New South Wales, Australia. The Department of Railways designed the tunnel and built it from 1891 to 1892. It is also known as Lapstone Hill tunnel and Former Glenbrook Railway and World War II Mustard Gas Storage Tunnel. The property is owned by Blue Mountains City Council and Land and Property Management Authority, an agency of the Government of New South Wales. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 5 August 2011.[3] The railway tunnel was originally part of the Glenbrook 1892 single-track deviation, which bypassed the Lapstone Zig Zag across the Blue Mountains. It is 634 metres; 693 yards (31.5 chains) long and is constructed in an 'S' shape with a gradient of 1:33.[4]

The tunnel was built to the east of Glenbrook railway station and opened on 18 December 1892. Due to the steep gradient, seepage keeping the rails wet causing slippage, poor ventilation and planned duplication of the track, plans were drawn up to bypass the steep route. Trains commonly stalled in the tunnel for some time before having to back the locomotive out of the tunnel for another attempt. The tunnel was closed on 25 September 1913, and was utilised for growing mushrooms. In 1942, during World War II, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) stockpiled bulk mustard gas stocks in preparation for a possible Japanese chemical weapons attack.[5] The facility was known as No. 2 Sub Depot of No. 1 Central Reserve RAAF and was vacated by the RAAF after the war. It features in the "Alcatraz Down Under" episode of Cities of the Underworld on the History Channel.[6][7][8][9][10]

in July 2021, the local state member Stuart Ayres announced that the NSW Government had allocated $2.5 million to progress the opening of the tunnel for public recreation[11]

History

Use as a railway tunnel

The original line of railway was opened in 1867, scaling the escarpment above Emu Plains by the Lapstone Zig Zag. At the top of the Zig Zag the railway followed the route now occupied by the Great Western Highway through Glenbrook as far as Blaxland. When increased rail traffic caused delays on the Lapstone Zig Zag, it was decided in 1891 that a tunnel should be built bypassing the Zig Zag. The tunnel and its new approaches were designed to form an elegant S-shape, starting at the Bottom Points of the Zig Zag and ending at old Glenbrook station (now demolished, on the present Great Western Highway).[3][12][citation needed]

The building of the tunnel in 1891-2 was contracted to George Proudfoot, whose labourers and their families were established in two substantial camps at either end of the works, one at Glenbrook, the other at Lapstone. Sir Arthur Streeton's famous painting 'Fire's On!', saw the building of the tunnel and the fatal blasting accident which killed Thomas Lawless become a part of Australian mythology as well as railway history.[12] Streeton was spending three months at Glenbrook at the end of 1891 where he was studying and painting the landscape. He had become interested in the construction of the railway tunnel and the engineering feat that was the Zig Zag Railway.[13] The tunnel was also depicted in several other works, both informal and informal. Among these were Cutting the Lapstone Tunnel (1892) and Sketch - Blue Mountains (1891).[3]

The new tunnel opened to traffic on 18 December 1892, but it was never a success, because of the steep incline and the suffocating atmosphere particularly in the west-bound trains. Traffic flow and water dripping from the roof also caused engines to slip badly on the reverse curve. The problem was finally addressed after the Lithgow Zig Zag deviation was completed in 1910 and the railway gangs were moved to Glenbrook. Bypassing Glenbrook Tunnel involved some major works, including a new viaduct[14] over Knapsack Gully to the east and the new line then ran through virgin country south of the old alignment as far as the present Lapstone station and then turned west through a short tunnel under The Bluff and finally north to the present Glenbrook station.[3][12][15]

Initially it was planned to continue using the 1892 Glenbrook Tunnel for up trains. When the new deviation opened on 11 May 1913 the tunnel was still used for east-bound trains. However, the deviation was quickly duplicated and a new "up line was activated in September. Glenbrook Tunnel was last used for trains on 25 September 1913 and old Glenbrook station was closed.[12] The lines in the tunnel were raised and the tunnel left to quietly decay.[3]

In 1913 the Glenbrook tunnel was leased from NSW Railways by Herbert Edward Rowe, an out of work master builder. Previously a Stan Breakspear had fenced off an area close to the tunnel where he kept a bull. The Rowes had the idea of growing mushrooms in the tunnel. They created living quarters from an old circus tent, a small cave and a culvert under the highway. Herbert Rowe built his own mushroom growing beds which were three metres wide with a narrow path down the left side for access and working space. About three quarters of the length of the tunnel was taken up by the beds. When the Rowes renewed their lease in 1936 the Commissioner of Railways warned them that in the event of war, they would be given three months notice to vacate the site. The Rowes are believed to have actually been given only one weeks notice to vacate the site when war broke out in September 1939.[3][16]:141–42

In 1930 Australia ratified the 1925 Geneva Protocol which banned the use of asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases in times of war for offensive purposes, following the experiences of chemical warfare during World War I.[3]

Weapons storage facility

Although tear gas was used as early as 1914, it was not until 1915 that poisonous gases were introduced into the battles of World War One. The first was chlorine gas which was introduced by the Germans at the Second battle of Ypres in April 1915. This was followed by the use of phosphene Gas, also introduced by the Germans. These attacked victims' respiratory organs causing coughing and choking.[3]

The Germans used Mustard Gas, a more advanced gas, for the first time at Riga (or Yperite) in September 1917. It caused both internal and external blistering in its victims. The blistering was often delayed and remained in the ground for weeks afterwards making capture of infected trenches dangerous. Protection against mustard gas was far more difficult than previous gases. Casualties decreased during the war with increased preparedness and death from gas became less common. However, often those who were exposed were often unable to seek employment once they were discharged from the army due to the gases effects. Following the Armistice the use of gas was viewed with horror, bringing about the Geneva Protocol. However, it is important to note that while the Protocol prevented signatories using gas for offensive purposes, it did not prevent a nation from manufacturing or importing chemical weapons for retaliatory purposes.[3]

The Geneva Protocol was drawn up and signed at the conference for the supervision of the international trade in arms and ammunition, which was held in Geneva under the auspices of the League of Nations from 4 May to 17 June 1925. France suggested that a protocol be drawn up on non-use of poisonous gases. At Poland's suggestion the prohibition was extended to bacteriological weapons. In the years prior to World War II most major powers ratified the protocol, except the U.S. and Japan. The British reserved the right to waive the protocol if in time of war their enemies disregarded the terms of the agreement. Countries around the world have continued to ratify the Protocol until at least 1991.[3]

Australia's ratification of the protocol was influenced by the experiences of Australian World War One soldiers who had suffered from the deadly and debilitating effects of gas exposure, particularly on the Western Front. Many were killed or maimed as the result of chemical attacks. The physical effects on survivors were clearly visible to those at home upon their return.[3]

Use during World War II

By 1937, two years before World War II commenced, Australia was already giving preliminary consideration to the need for procurement of gas for war time defence purposes. Early in 1942 the Japanese southward advance, particularly the fall of Singapore, caused Australia to prepare for possible invasion. Of particular concern was whether Japan would use chemical weapons as it had in China. Australia requested chemical warfare stocks from Britain in March. The response from Britain to supply Australia was swift and the first supplies docked in Australia in May 1942. Later stocks would also come from the United States.[16]:1–20 Australia would eventually hold close to 1 million individual chemical munitions weapons, including at least 16 different types of mustard gas. Thirty-five types of chemical weapons were eventually located at fifteen major storage depots across Australia.[3]

The first stocks of chemical weapons destined for the RAAF were stored in the Blue Mountains while those for the army went to Albury. Naval stocks were stored at the Newington Armory in Sydney. The RAAF stocks were stored in disused tunnels, chosen because of the lower fluctuation in temperature, protection from high temperatures and constant humidity. In places such as Malaya, caves were used for the same purposes and the tunnels were anticipated to simulate the same conditions as the caves. Industrial scale production or bulk manufacturing of chemical warfare agents did not and has not taken place within Australia, although some chemical agents have been produced here as by-products of other industrial processes or in bulk for other purposes. There has also been small scale manufacture of chemical agents for experimental and testing purposes.[3][16]:29–30, 128

The Glenbrook tunnel was one of fifteen bulk chemical storage facilities established in Australia - seven in New South Wales, six in Queensland, one in the Northern Territory and one in Victoria. Six were supervised by the United States, including Kingswood in NSW, and the remainder by Australia. Only four of these included tunnels for storage purposes. These were Marrangaroo, Glenbrook and Clarence in the Blue Mountains and Picton south of Sydney. They were all Australian supervised sites.[16]:553 Marrangaroo and Glenbrook were the first of the tunnels established followed by Picton and then Clarence. The Picton tunnel was constructed as part of the original main southern railway line. The remaining three were a part of the Zig Zag railway line. The four tunnels formed the base for the Royal Australian Air Force's No. 1 Central Reserve. The headquarters for No 1CR were based at the combined RAAF-Army depot at Marangaroo, several kilometres from the Marangaroo tunnel. No. 1 CR acted as a central depot for chemical and non chemical stocks and as a replenishment centre for NSW. The location of the tunnels also placed them out of the range of aircraft carriers and out of aerial view, thus protecting them from air attack.[3][16]:129–31

The British oversaw the initial establishment of chemical agents handling procedures. On 6 January 1942 the Air Board approved the take-over of the disused 660-metre (2,170 ft) railway tunnel at Glenbrook by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) for the storage of bombs. On 9 August 1942 arrangements for the first intake of chemicals at Glenbrook were advised with material being received from the ship MV Nigerstrromm.[5] When further supplies of chemicals arrived it was decided to move high explosive stocks from Glenbrook and Picton and devote these tunnels to gas stocks alone. Glenbrook housed mainly mustard gas from late August 1942. The RAAF stacked the Glenbrook tunnel from end to end with containers to store thousands of tonnes of mustard gas, a thick fluid that looked like oil. To accommodate facilities for maintenance and inspection, venting and decanting containers and decontamination of damaged hardware, an area was set up in the lower/eastern end cutting leading from the tunnel.[3][16]:142–44

Additional shipments of gas in 1943-44 compelled the commissioning of Clarence tunnel to take the overflow. By 7 February 1944 the transfer of chemical weapons stocks from No. 2 Sub Depot, Glenbrook to Clarence Tunnel began. By August 1944 the RAAF decided that chemical weapons stocks and equipment other than obsolete items should be held substantially in forward areas and that No. 1 CR would become a transit point rather than a storage area to facilitate the supply of chemical weapons to forward unit should retaliatory chemical warfare action be sanctioned. two storage locations were subsequently chosen in north eastern Australia.[3][16]:129–131, 142

During the peak period for the arrival of chemicals from Great Britain and the African desert zone Glenbrook railway siding was inadequate for the transport operations and associated influx of railway wagons and motor vehicles. Therefore, trains were kept at Penrith and batches of 14-20 wagons brought to Glenbrook as required.[3][16]:142–44

In 1946, following the end of the war, the Australian Defence Committee agreed to the Army and RAAF requests to dispose of chemical ammunition. The Australian Government faced a dilemma as to how to dispose of the stocks of chemicals. Neither the Army or the Air Force had experience with disposal. As a result, trials were conducted to determine the best form of large scale chemical destruction. Burning, sea dumping and venting were found appropriate for the different types of chemicals. Fire was found to be the most appropriate for mustard gas. Gas was burned from storage sites at Talmoi and 88 Mile. The stocks at Marangaroo and Glenbrook were the last to be burned. The disposal took place in the Newnes State Forest during February and March 1946 when 2,000 tonnes (2,200 short tons) were incinerated. Post war inspections showed that the burn had been incomplete and redisposal operations were conducted between 1947 and 1949, including reburning some items and the use of bleach. Final decontamination took place in 1980 when approximately 2,500 tonnes (2,800 short tons) of mainly soil residue were removed from the Newnes State Forest burn site to the nearby Marrangaroo Ammunition Depot to be burned in a pit and bleached.[16]:308–10 Glenbrook later reverted to its former use as a mushroom farm.[3]

Glenbrook was considered the most pleasant of the tunnel depots by the men who worked with the gas. The site was described in 1943 as about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) into the bush. The camp consisted of the headquarters, orderly room a store, alcove for maintenance carpenter, mess hut with a big stone fireplace and an open fire to cook on, masonite and wooden framed sleeping huts which had replaced tents. The huts had shutters at the top and bottom which could be propped open shower and toilet blocks and a small transport section hut. Workers were required to do maintenance on the containers wearing gumboots, rubber gloves and heavy woollen clothing. Small burns were common if the men got gas on their skin. During the summer months RAAF staff from the Glenbrook camp were called out to fight bushfires.[16]:142–152 The purpose of their presence at Glenbrook was a long-held secret as was the testing and later disposal of the gas.[3]

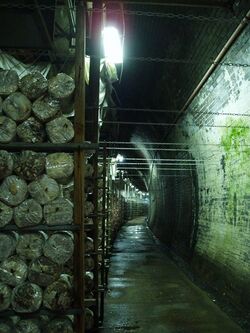

During operation the s curved, 650-metre (2,130 ft) tunnel was long and dark with widely spaced lighting. On the left hand side at the start of the tunnel were small containers, canisters in wooden crates. About midway canisters were located on one side and drums on the other. Further along, the sides that the canisters and drums were stored on were reversed. The tunnel had very little clearance, making it difficult for the trucks to back into the tunnel to load and unload the chemicals.[16]:150–53 The exterior ends of the tunnel were constructed of brick with stone capping. During WWII the RAAF installed a concrete grid floor in the tunnel and installed a telephone system for security purposes. It was apparently initially used by the RAAF to store 227-kilogram (500 lb) bombs.[3]

Current-day use

Post World War II, all four tunnels were used for mushroom growing purposes. Glenbrook tunnel has since been abandoned. In 1992 the lessee commenced growing exotic mushrooms not previously produced in Australia. Other tunnels not used for mustard gas storage have also been used as mushroom tunnels, including one at Mittagong and another near Helensburgh. The Marrangaroo storage tunnel has also been abandoned, while the Clarence tunnel forms part of the Zig Zag Tourist Railway and Picton has become a tourist attraction with a "ghostly past". The World War II history of the tunnel's use was not widely known until the early twentyfirst century. This "hidden history" was the subject of significant interest when it was finally made known.[3]

In 2021, it was announced that the state government will be funding works to transform the tunnel as a publicly accessible walking track, cycleway, and heritage tourist attraction, as well as better connecting the Lower Blue Mountains to neighboring Leonay and Penrith.[17]

Description

The S curved railway tunnel is constructed internally of brick (some areas are cement rendered) and a cement floor. It is approximately 660 metres (2,170 ft) in length, passing beneath the ridge which carried the Zig Zag line and now the Great Western Highway. The western end, which is the main entry point, is located near to the edge boundary of Knapsack Reserve. The eastern end is located near Railway Reserve/Darkes Common. To the south of the main entry is the Great Western Highway. Knapsack Reserve is north of the main entry.[3]

The tunnel is laid out in reverse curves with transitions. The western entry is accessed from an unformed road through a series of large, older tin shed and outbuildings used by the existing tenant for business purposes. The road gives way to a gravel track large enough for use by vehicles. Vegetation is encroaching on the track. This appears to be covering stone walls which would have formed the 60-metre (200 ft) western railway approaches dug out when creating the tunnel and the deviation. An open shed is located close to the tunnel entry sheltering a variety of equipment. The eastern end was not accessible in 2010.[3]

The entry is characterised by a large three ring brick parabolic arch with a sandstone outer curve and a horizontally articulated entablature constructed of axe-faced and margined stone ashlars. The top of the entablature course to the former rail level is approximately 8 metres (26 ft). The face brickwork of the surround is plumb and laid in English bond. The arch is flanked by brick buttresses/battered piers on either side of the entrance. Beyond these are short sandstone retaining walls laid in squared rubble. An undated light fitting on bracket is located centrally over the arch. The arch opening has been filled in with sheets of iron, exhaust fan and a roller door to secure and ventilate the tunnel for the current occupier.[3]

The eastern entry is similar to the western entry, although the flanking piers are a little wider due to the slightly wider railway cutting. This is in part due to the approach to hillside at the western cutting being generally steeper.[3]

Inside, both painted and unpainted brick and cement rendered wall and roof surfaces are visible throughout the tunnel. The brick work is laid in English bond for 40 courses above the present floor, above which the height changes to stretcher bond. The shape of the tunnel is a continuation of the entrance arch. Weep holes are located in the walls about two courses above ground level that are one course high and about 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) apart. A variety of services suspended from the roof and fixtures primarily associated with the current use are visible, including piping and racking. A strip of fluorescent lighting is located down the centre of the tunnel. What appear to be drainage ditches are located along both walls the full length of the tunnel. All railway tracks have been removed and the concrete floor has replaced what was probably a ballast surface, as has evidence of the mustard gas storage facility. The floor has an even grade of 1 in 33 upwards from east to west.[3]

Regularly placed recessed refuges designed as safe spaces for railway workers caught in the tunnel as a train approached are located down both sides of the tunnel about 48 metres (157 ft) apart. They are 686 millimetres (27.0 in) deep, 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in) wide and 1.98 metres (6 ft 6 in) high and are characterised by a three ring segmental arch.[3]

Condition

As at 15 December 2010, the tunnel structure appears to be in very good condition visually. Mushroom racks and associated infrastructure and infil at the end of the tunnel appear to be non structural and easily reversed if desired.[3]

The tunnel structure does not appear to have been significantly altered. The most obvious alterations are the apparent replacement of the railway tracks and ballast with a concrete floor, and removal of any purpose built facilities associated with the mustard gas storage.[3]

Modifications and dates

- 1913 - Railway lines removed

- c. 1913 - mushroom growing beds installed

- c. 1939-42 - mushroom growing beds removed for establishment of mustard gas storage

- Post 1945 - converted for mushroom growing[3]

Heritage listing

As at 22 February 2011, the former Glenbrook Railway Tunnel and Mustard Gas Storage Depot has outstanding significance as one of a series of only four tunnels, in NSW that physically embody Australian policy towards bulk chemical gas storage during World War II for defensive purposes on home soil. The presence of the gas for use only when the opposition attacked with chemical weapons, represents Australia's ongoing commitment to honouring the articles of the 1925 Geneva Protocol to which Australia submitted an instrument of ratification in 1930. It also demonstrates Australia's increasing awareness and fear of the threat posed by Axis forces, particularly Japan and the preparedness of Australia and the Allied Forces to employ antihumanitarian weapons widely condemned in World War One, in the event that the Axis powers used such weapons in an attack.[3]

Glenbrook Railway and World War II Mustard Gas Storage Tunnel was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 5 August 2011 having satisfied the following criteria.[3]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

The tunnel has state historical significance as one of only four tunnels located in NSW, secretly identified and established for storage of chemical weapons for defence purposes in the event of an attack on Australian shores during World War II. The tunnel is a reminder of this secret NSW and Australian military history not publicly known about until the first years of the twenty first century. The facility was part of a much larger process of acquisition, storage, testing and disposal of poisonous gas. Many men suffered from contact with the gas and were unable to discuss their experiences of war on the home front for many years. Its establishment was a direct response to the Australian government's fear of invasion by the Japanese, particularly after the fall of Singapore to Japan in 1942, and the potential for the Japanese to use poisonous gas against Australia. The facility also reflects the changing course of World War II and the willing use by Australia of clauses in the Geneva Protocol which prevented signatories from utilising poisonous gas for attack purposes, but did allow them to use it for retaliatory purposes in the event that they were attacked with poisonous gas.[3]

The tunnel has local significance as a railway tunnel constructed to bypass the Lapstone Zig Zag as rail traffic, and subsequently delays, increased on the zig zag line. In the twenty years that it operated the tunnel gained a fearsome reputation among locomotive crews and travellers for the unpleasantness of the journey due to the choking smoke and fumes.[3]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

The site has historical associations at a state and national level with the British and United States Military forces who were involved in the establishment of chemical weapons in Australia during World War II. It also has associations with the Defence Force Armourers responsible for maintaining the facilities in Australia, in particular the Royal Australian Air Force's No 1 Central Reserve. The tunnel has high state and national significance for its direct association with events which directly resulted from the Australian and other government's ratification of the 1925 Geneva Protocol banning the use of chemical warfare for offensive purposes.[3]

As the subject of the 1891 painting, Fire's On by Arthur Streeton, it is the inspiration for a picture that has been described as one of the great icons of Australian landscape painting. The tunnel and its eastern approaches in particular also featured in a number of other works by Streeton, thereby making the site as subject of these paintings significant to the state.[3]

The place has strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The Glenbrook Tunnel has state significant as being important to Defence Force Armourers and their families across NSW as evidence of the long hidden and previously disbelieved story of their work during World War II. It is also important to the defence forces generally as evidence of a previously suppressed aspect of their history.[3]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

The Glenbrook Tunnel is state significant, being rare as one of only four tunnels in New South Wales identified for chemical gas storage purposes during World War II, three of which are located within the Blue Mountain region. Unlike the remaining three tunnels, the Glenbrook tunnel is the only tunnel to retain its original post railway use, mushroom growing.[3]

The tunnel has local significance as the only major item of surviving fabric from one of the three railway ascents of the eastern escarpment.[3]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

Glenbrook tunnel has local significance as being representative of tunnels constructed on the Main Western Line from the 1890s and into the early twentieth century to cater for increasing traffic on the railway line. The tunnel is a fine example of engineering in brickwork, displaying a substantial vaulted form of elliptical cross section, double curved in plan.[3]

See also

- Glenbrook Deviation (1892)

- Lapstone Zig Zag

- List of tunnels in Australia

References

- ↑ "The Lapstone Tunnel.". The Evening News (New South Wales, Australia) (7972): p. 3. 19 December 1892. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article113318342.

- ↑ "LAPSTONE HILL DEVIATION.". The Australian Star (New South Wales, Australia) (1576): p. 7. 20 December 1892. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article227301375.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 3.29 3.30 3.31 3.32 3.33 3.34 3.35 3.36 3.37 3.38 3.39 "Glenbrook Railway and World War Two Mustard Gas Storage Tunnel". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5061088.

- ↑ "Glenbrook Tunnel". Rolfe Bozier. http://www.nswrail.net/locations/show.php?name=NSW:Glenbrook+Tunnel+(1st)&line=NSW:main_west:1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Plunkett 2009.

- ↑ "Alcatraz Down Under episode". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wKQUED3G0ho.

- ↑ Madigan, Damien (27 February 2008). "Author lifts lid on chemical wartime history". http://bluemountains.yourguide.com.au/news/local/news/general/author-lifts-lid-on-chemical-wartime-history/307763.aspx.

- ↑ "Glenbrook's secret history". 26 March 2008. http://bluemountains.yourguide.com.au/news/local/news/general/glenbrooks-secret-history/402833.aspx.

- ↑ Walker, Frank (20 January 2008). "Deadly chemicals hidden in war cache". http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/deadly-chemicals-hidden-in-war-cache/2008/01/19/1200620272396.html.

- ↑ "Geoff's terrible secret war". 19 February 2008. http://penrith-press.whereilive.com.au/news/story/geoffs-terrible-secret-war/.

- ↑ Madigan, Damien (2021-07-05). "Historic rail tunnel to be opened to community following new funding injection". Blue Mountains Gazette. https://www.bluemountainsgazette.com.au/story/7323551/historic-rail-tunnel-to-be-opened-to-community-following-new-funding-injection/.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Blue Mts Heritage Study.

- ↑ National Gallery 2010.

- ↑ Template:Cite NSW HD

- ↑ Pratten & Irving 1993, p. 32-33.

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 Plunkett 2007.

- ↑ "Historic rail tunnel to be opened to the community". Stuart Ayres MP. 2021-07-02. https://www.stuartayres.com.au/media/media-releases/historic-rail-tunnel-be-opened-community.

Bibliography

- "Bunkers, Tunnels and Fortifications in Australia during World War Two.". 2009. http://home.st.net.au/~dunn/ozatwar/bunkers.htm.

- Gillis, Richard G. (1985). The Gillis Report: Australian Field Trials with Mustard gas 1942-45.. Peace Research Centre, Australian National University.. http://mustardgas.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Gillis-Report-1985-Australian-Field-Trials-With-Mustard-Gas-1942-1945.pdf.

- International Committee of the Red Cross (2005). "International Humanitarian Law - Treaties and Documents". http://cicr.org/ihl.nsf/INTRO/280?OpenDocument.

- National Gallery of Australia (2010). "Turner to monet. The Triumph of Landscape Education Resource". http://nga.gov.au/Exhibition/Turnertomonet/Detail.cfm?IRN=165173&BioArtistIRN=12361&MnuID=2.

- Plunkett, Geoff (2009). "Chemical Warfare in Australia". http://mustardgas.org/.

- Plunkett, Geoff (2007). Chemical warfare in Australia. Australian Military History Publications. ISBN 978-1-876439-88-0. https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/11353835.

- Pratten, Christopher; Irving, Robert (1993). Lapstone Hill Tunnel Conservation and Management Plan. https://library.bmcc.nsw.gov.au/client/en_AU/default/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fSD_ILS$002f0$002fSD_ILS:3533/one.

- Wildman, Don (2009). "Cities of the Underworld - Alcatraz Down Under". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kp1EFlngjKQ.

Attribution

External links

- Australian Bunker & Military Museum

- "Old Glenbrook Tunnel". http://infobluemountains.net.au/rail/lower/glen-tunnel-old.htm.

- "Bridges around the Penrith Area". Penrith City Council. http://www.penrithcity.nsw.gov.au/index.asp?id=259.

- "Image of RAAF Mustard Gas Stockpile". http://bluemountains.yourguide.com.au/multimedia/images/full/143898.jpg.

- East End along Tunnel Gully Reserve - [ ⚑ ] 33°46′04″S 150°38′06″E / 33.76777°S 150.63509°E

- West End at Mushroom Farm - [ ⚑ ] 33°45′49″S 150°37′48″E / 33.763581°S 150.629925°E

|