Chemistry:Peak copper

Peak copper is the point in time at which the maximum global copper production rate is reached. Since copper is a finite resource, at some point in the future new production from mining will diminish, and at some earlier time production will reach a maximum. When this will occur is a matter of dispute. Unlike fossil fuels, copper is scrapped and reused, and it has been estimated that at least 80% of all copper ever mined is still available (having been repeatedly recycled).[1]

Copper is among the most important industrial metals, ranking third after iron and aluminium in terms of quantity used.[2] It is valued for its heat and electrical conductivities, ductility, malleability and resistance to corrosion. Electrical uses account for about three quarters of total copper consumption, including power cables, data cables and electrical equipment. It is also used in cooling and refrigeration tubing, heat exchangers, water pipes and consumer products.[2]

Copper has been used by humans for at least 10,000 years. More than 97% of all copper ever mined and smelted has been extracted since 1900[citation needed]. The increased demand for copper due to the growing Indian and Chinese economies since 2006 has led to increased prices and an increase in copper theft.[3]

History

Concern about the copper supply is not new. In 1924 geologist and copper-mining expert Ira Joralemon warned:[4]

- ... the age of electricity and of copper will be short. At the intense rate of production that must come, the copper supply of the world will last hardly a score of years. ... Our civilization based on electrical power will dwindle and die.

Copper demand

Total world production is about 18 million metric tons per year.[2] Copper demand is increasing by more than 575,000 tons annually and accelerating.[3] Based on 2006 figures for per capita consumption, Tom Graedel and colleagues at Yale University calculate that by 2100 global demand for copper will outstrip the amount extractable from the ground.[5] China accounted for more than 22% of world copper demand in 2008,[6] and is nearly 40% in 2014.

For some purposes, other metals can substitute, aluminium wire was substituted in many applications, but improper design resulted in fire hazards.[7] The safety issues have since been solved by use of larger sizes of aluminium wire (#8AWG and up), and properly designed aluminium wiring is still being installed in place of copper. For example, the Airbus A380 uses aluminum wire in place of copper wire for electrical power transmission.[8]

Copper supply

Globally, economic copper resources are being depleted with the equivalent production of three world-class copper mines being consumed annually.[3] Environmental analyst Lester Brown suggested in 2008 that copper might run out within 25 years based on what he considered a reasonable extrapolation of 2% growth per year.[9]

New copper discoveries

Fifty-six new copper discoveries have been made during the three decades 1975–2005.[3] World discoveries of new copper deposits are said to have peaked in 1996.[10] However, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS), remaining world copper reserves have more than doubled since then, from 310 million metric tons in 1996[11] to 690 million metric tons in 2013.[12]

Production

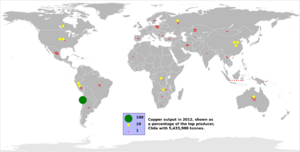

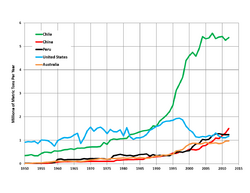

As shown in the table below, the three chief national producers of copper, respectively, in 2002, were Chile, Indonesia, and the United States. In 2013, they were Chile, China, and Peru. Twenty-one of the 28 largest copper mines in the world (as of 2006) are not amenable to expansion.[3]

| Country | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4,580 | 4,860 | 5,410 | 5,320 | 5,560 | 5,700 | 5,330 | 5,390 | 5,420 | 5,260 | 5,430 | 5,780 | 5,750 | 5,760 | |

| 585 | 565 | 620 | 640 | 890 | 920 | 950 | 995 | 1,190 | 1,310 | 1,630 | 1,600 | 1,760 | 1,710 | |

| 843 | 850 | 1,040 | 1,090 | 1,049 | 1,200 | 1,270 | 1,275 | 1,250 | 1,240 | 1,300 | 1,380 | 1,380 | 1,700 | |

| 1,140 | 1,120 | 1,160 | 1,150 | 1,200 | 1,190 | 1,310 | 1,180 | 1,110 | 1,110 | 1,170 | 1,250 | 1,360 | 1,380 | |

| 873 | 870 | 854 | 930 | 859 | 860 | 886 | 854 | 870 | 958 | 958 | 990 | 970 | 971 | |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 343 | 520 | 600 | 970 | 1,030 | 1,020 | |

| 695 | 700 | 675 | 675 | 725 | 730 | 750 | 725 | 703 | 713 | 883 | 833 | 742 | 732 | |

| 330 | 330 | 427 | 450 | 476 | 530 | 546 | 697 | 690 | 668 | 690 | 760 | 708 | 712 | |

| 600 | 580 | 546 | 580 | 607 | 585 | 607 | 491 | 525 | 566 | 579 | 632 | 696 | 697 | |

| 1,160 | 1,170 | 840 | 1,050 | 816 | 780 | 651 | 996 | 872 | 543 | 360 | 504 | N/A | N/A | |

| 330 | 330 | 406 | 420 | 338 | 400 | 247 | 238 | 260 | 443 | 440 | 480 | 515 | 594 | |

| 490 | 480 | 461 | 400 | 457 | 460 | 420 | 390 | 380 | 417 | 424 | 446 | N/A | N/A | |

| 503 | 500 | 531 | 530 | 512 | 470 | 430 | 439 | 425 | 427 | 427 | 429 | N/A | N/A | |

| Other countries | 1,500 | 1,500 | 1,610 | 1,750 | 1,835 | 1,800 | 2,030 | 2,190 | 1,900 | 1,970 | 2,000 | 2,200 | 3,600 | 3,800 |

| World | 13,600 | 13,800 | 14,700 | 15,000 | 15,100 | 15,500 | 15,600 | 16,100 | 16,100 | 16,100 | 16,900 | 18,200 | 18,400 | 19,100 |

Reserves

Copper is a fairly common element, with an estimated concentration of 50–70 ppm (0.005–0.007 percent) in earth's crust (1 kg of copper per 15–20 tons of crustal rock).[25] A concentration of 60 ppm would multiply out to 1.66 quadrillion tonnes over the 2.77×1022 kg mass of the crust,[26] or over 90 million years' worth at the 2013 production rate of 18.3 MT per year. However, most of it cannot be extracted profitably at the current level of technology and the current market value.[citation needed]

The USGS reported a current total reserve base of copper in potentially recoverable ores of 1.6 billion tonnes as of 2005, of which 950 million tonnes were considered economically recoverable.[27] A 2013 global assessment identified "455 known deposits (with well-defined identified resources) that contain about 1.8 billion metric tons of copper", and predicted "a mean of 812 undiscovered deposits within the uppermost kilometer of the earth's surface" containing another 3.1 billion metric tons of copper "which represents about 180 times 2012 global copper production from all types of copper deposits."[28]

| Country | 1996 Reserves | Percent | 2015 Reserves | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 88,000 | 28.4% | 209,000 | 29.9% | |

| 7,000 | 2.26% | 93,000 | 13.2% | |

| 7,000 | 2.26% | 68,000 | 9.71% | |

| N/A | N/A | 38,000 | 5.43% | |

| 45,000 | 14.5% | 35,000 | 5.00% | |

| 3,000 | 0.968% | 30,000 | 4.29% | |

| 20,000 | 6.45% | 30,000 | 4.29% | |

| 20,000 | 6.45% | 28,000 | 4.00% | |

| 11,000 | 3.55% | 25,000 | 3.57% | |

| N/A | N/A | 20,000 | 2.86% | |

| 12,000 | 3.87% | 20,000 | 2.86% | |

| 11,000 | 3.55% | 11,000 | 1.57% | |

| 14,000 | 4.52% | 6,000 | 0.86% | |

| 11,000 | 3.55% | N/A | N/A | |

| 7,000 | 2.26% | N/A | N/A | |

| Other countries | 55,000 | 17.7% | 90,000 | 12.9% |

| World | 310,000 | 100% | 700,000 | 100% |

Known resources

Recycling

In the US, more copper is recovered and put back into service from recycled material than is derived from newly mined ore. Copper's recycle value is so great that premium-grade scrap normally has at least 95% of the value of primary metal from newly mined ore.[30] In Europe, about 50% of copper demand comes from recycling (as of 2016).[31]

As of 2011[update], recycled copper provided 35% of total worldwide copper usage.[32]

Undiscovered conventional resources

Based on discovery rates and existing geologic surveys, researchers estimated in 2006 that 1.6 billion metric tons of copper could be brought into use. This figure relied on the broadest possible definition of available copper as well as a lack of energy constraints and environmental concerns.[27]

The US Geological Survey estimated that, as of 2013, there remained 3.5 billion metric tons of undiscovered copper resources worldwide in porphyry and sediment-hosted type deposits, two types which currently provide 80% of mined copper production. This was in addition to 2.1 billion metric tons of identified resources. Combined identified and estimated undiscovered copper resources were 5.6 billion metric tons,[33] 306 times the 2013 global production of newly mined copper of 18.3 million metric tons.

Unconventional resources

Deep-sea nodules are estimated to contain 700 million tonnes of copper.[15]

Copper prices

The international price of copper struck a first peak level on 6 March 2008, on the London Metal Exchange (LME), surging 5.8% over the previous trading day to US$4.02 per pound. The previous record was set on 12 May 2006, at US$3.98/lb. The price increased rapidly in early 2008, rising 23% in February 2008,[34] then declined 40% before December 2008,[35] and reached US$1.30 by year's end.[36] In February 2011 the price peaked at US$4.58/lb[37] but then fell to US$3.18/lb during 2013.

Criticism

Julian Simon was a senior fellow at the Cato Institute and a professor of business and economics. In his book The Ultimate Resource 2 (first printed in 1981 and reprinted in 1998), he extensively criticizes the notion of "peak resources", and uses copper as one example. He argues that, even though "peak copper" has been a persistent scare since the early 20th century, "known reserves" grew at a rate that outpaced demand, and the price of copper was not rising but falling over the long run. For example, even though world production of copper in 1950 was only one-eighth of what it was in the early 2000s, known reserves were also much lower at the time – around 100 million metric tons – making it appear that the world would run out of copper in 40 to 50 years at most.

Simon's own explanation for this development is that the very notion of known reserves is deeply flawed,[38] as it does not take into account changes in mining profitability. As richer mines are exhausted, developers turn their attention to poorer sources of the element and eventually develop cheap methods of extracting it, raising known reserves. Thus, for example, copper was so abundant 5000 years ago, occurring in pure form as well as in highly concentrated copper ores, that prehistoric peoples were able to collect and process it with very basic technology. As of the early 21st century, copper is commonly mined from ores that contain 0.3–0.6% copper by weight. Yet, despite the material being far less widespread, the cost of, for example, a copper pot was vastly lower in the late 20th century than 5000 years ago.[39]

See also

- 2000s commodities boom

- Hubbert peak theory

- List of copper alloys

- Mineral resource classification

- Peak minerals

References

- ↑ "Copper Recycling - Copper Alliance" (in en-US). https://copperalliance.org/resource/copper-recycling/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Copper Statistics and Information | U.S. Geological Survey" (in en). http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Leonard, Andrew (2 March 2006). "Peak copper?". Salon. http://www.salon.com/2006/03/02/peak_copper/.

- ↑ "Copper and electricity to vanish in twenty years?". Engineering and Mining Journal 118 (4): 122. 26 July 1924.

- ↑ David Cohen (23 May 2007). "Earth's natural wealth: an audit". New Scientist (2605): 34–41. http://www.science.org.au/nova/newscientist/027ns_005.htm?id=mg19426051.200&print=true. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- ↑ Glaister, Dan; Branigan, Tania; Bowcott, Owen (20 March 2008). "Deaths and disruption as price rise sees copper thefts soar". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/mar/20/internationalcrime.

- ↑ http://www.cpsc.gov//PageFiles/118856/516.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ↑ Hellemans, Alexander (1 January 2007). "Manufacturing Mayday: Production glitches send Airbus into a tailspin". IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/aerospace/aviation/manufacturing-mayday.

- ↑ Brown, Lester (2006). Plan B 2.0: Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and a Civilization in Trouble. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 109. ISBN 0-393-32831-7. https://archive.org/details/planb20rescuingp00brow_0.

- ↑ "Peak Copper Means Peak Silver". Charleston Voice. 29 December 2005. http://news.silverseek.com/CharlestonVoice/1135873932.php.

- ↑ "Copper Statistics and Information | U.S. Geological Survey" (in en). http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/240397.pdf.

- ↑ "Copper Statistics and Information | U.S. Geological Survey" (in en). http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2014-coppe.pdf.

- ↑ "pg. 54 – Copper". USGS. 2004. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/coppemcs04.pdf.

- ↑ "pg. 56 – Copper". USGS. 2006. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/coppemcs06.pdf.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "pg. 54 – Copper". USGS. 2008. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2008-coppe.pdf.

- ↑ "pg. 49 – Copper". USGS. 2010. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2010-coppe.pdf.

- ↑ "pg. 49 – Copper". USGS. 2011. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2011-coppe.pdf.

- ↑ "pg. 49 – Copper". USGS. 2012. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2012-coppe.pdf.

- ↑ "pg. 49 – Copper". USGS. 2013. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2013-coppe.pdf.

- ↑ "pg. 48 – Copper". USGS. 2014. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2014-coppe.pdf.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "pg. 49 – Copper". USGS. 2015. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2015-coppe.pdf.

- ↑ "pg. 55 – Copper". USGS. 2016. https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2016-coppe.pdf.

- ↑ "pg. 55 – Copper". USGS. 2017. https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/mcs-2017-coppe.pdf.

- ↑ "Copper Statistics". USGS. 2016. https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/historical-statistics/ds140-coppe.xlsx.

- ↑ Emsley, John (2003). Nature's building blocks: an A–Z guide to the elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 121–125. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8. https://archive.org/details/naturesbuildingb0000emsl.

- ↑ Peterson, B. T.; Depaolo, D. J. (2007-12-01). "Mass and Composition of the Continental Crust Estimated Using the CRUST2.0 Model". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts 2007: V33A–1161. Bibcode: 2007AGUFM.V33A1161P. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2007AGUFM.V33A1161P.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Biello, David (17 January 2006). "Measure of Metal Supply Finds Future Shortage". Scientific American. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=measure-of-metal-supply-f.

- ↑ Hammarstrom, Jane M. (29 October 2013). "Undiscovered Porphyry Copper Resources—A Global Assessment". The Geological Society of America: Annual Meeting & Expo. https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2013AM/webprogram/Paper226200.html.

- ↑ "pg. 50 – Copper". USGS. 1996. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/copper/coppemcs96.pdf.

- ↑ "Copper in the USA: Bright Future – Glorious Past". Copper Development Association. http://www.copper.org/education/history/g_fact_future.html.

- ↑ Europe’s Copper Industry

- ↑ icsg. "International Copper Study Group - Homepage" (in en-US). https://icsg.org/.

- ↑ Kathleen M. Johnson and others, Estimate of undiscovered copper resources of the world, 2013, US Geological Survey, Fact Sheet 2014–3004, Jan. 2014.

- ↑ "International copper price hits record high". China View. 8 March 2008. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2008-03/08/content_7744648.htm.

- ↑ Jha, Dilip Kumar (2008-11-30). "Falling demand may dent base metal prices". Business Standard India. https://www.business-standard.com/article/markets/falling-demand-may-dent-base-metal-prices-108113001038_1.html.

- ↑ $1.30 price. Charts3.barchart.com. Retrieved on 14 March 2014.

- ↑ London Metal Exchange: Copper . LME.com. Retrieved on 14 March 2014.

- ↑ Simon, Julian (16 February 1998) Chapt 12, "People, Materials, and Environment" in The Ultimate Resource II.

- ↑ "The Ultimate Resource II: People, Materials, and Environment". http://www.juliansimon.com/writings/Ultimate_Resource/.

External links

- Copper.org

- "US Minerals Databrowser". Mazama Science. http://mazamascience.com/Minerals/USGS.

- R. B. Gordon*, M. Bertram and T. E. Graedel (31 January 2006). "Metal Stocks and Sustainability". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (U.S. National Academy of Sciences) 103 (5): 1209–1214. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509498103. PMID 16432205. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..103.1209G.