Distributive law between monads

In category theory, an abstract branch of mathematics, distributive laws between monads are a way to express abstractly that two algebraic structures distribute one over the other.

Suppose that and are two monads on a category C. In general, there is no natural monad structure on the composite functor ST. However, there is a natural monad structure on the functor ST if there is a distributive law of the monad S over the monad T.

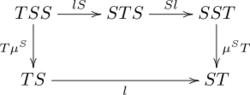

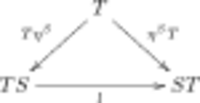

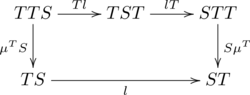

Formally, a distributive law of the monad S over the monad T is a natural transformation

such that the diagrams

This law induces a composite monad ST with

- as multiplication: ,

- as unit: .

Examples

Monoids

Informally, one might say that the free monoid on a set is given by "the free semigroup, plus an identity element". We can formalise this intuition, using the fact that both the free semigroup and the "free element" functors are monads.[1] Explicitly, consider the monads

- ,

(here addition denotes disjoint union), with unit maps given by:

- .

The multiplication map sends both elements of 2 to that of 1, but the multiplication on is a bit more tricky to describe. First, note that an arbitrary element of is just a finite (nonempty) string of elements of . The multiplication map should therefore take a string of words on to one word. We choose to be the concatenation of all (finitely many) words in .

What does a distributive law mean here? It takes a word on the set to either a word on , or the disjoint point in . We choose the map that interprets the unit element as the empty word; explicitly:

where is the word derived from by removing all instances of , unless is all 's, in which case it's defined to be . The idea, in short, is this: if we view words on as formal products of elements (i.e., the free semigroup operation), then encodes that the freely added element can be incorporated into the semigroup as a unit element (thereby making the structure into a monoid). Let us check that all the diagrams in the definition commute.

- ,

being the elements of each copy of in , and where denotes the word with every instance of replaced by .

- ,

and note that for we have , as required.

- ,

where: is the concatenation of all words in , i.e. the multiplication on ; and is the result of replacing every word in with .

- .

In summary, the four commutation requirements encode the following ideas:

- "Deleting" elements behaves like replacing them with the identity, .

- Any word on doesn't contain the element , so . In other words, truly is a disjoint union.

- In a list of words , removing any instance of in , removing any remaining "empty word" , and concatenating the resulting list, yields the same result as first concatenating then removing all instances of .

- , as already covered in 2; and , meaning we should interpret as the empty word.

Rings

This is the original example given by Beck,[2] and is the motivation for the term "distributive law". Consider the two monads which send a set to (the underlying set of) the free commutative group and the free monoid on it, respectively. We shall regard the formal group operation as addition, and that of the monoid as multiplication. In this case, both composites and give the free ring functor. We can now use the fact that the free ring admits a distributive law to show that it's also a monad.

The distributive law of G over M means exactly that a product of sums (i.e. an element of ) can be identified with a sum of products (an element of ). Note that we say , the additive group, distributes over , the multiplicative monoid - contrary to the usual convention; see the next section.

Terminology

The original description by Beck calls a distributive law of S over T.[2] However, some authors prefer the reverse terminology, where is instead said to be a distributive law of T over S; this is because, arguably, the latter convention corresponds more closely to the usual distributive law between multiplication and addition - multiplication is typically said to distribute over addition, by which one means that a product of sums can be rewritten as a sum of products (see Examples). Nevertheless, both terminologies are in use in different sources, and the original is what this article uses.[3]

Related notions

BD-law

In the case where , the distributive law map reduces to , and one may impose some additional conditions. is called a BD-law on if:

- (D) is a distributive law, and

- (B) it satisfies the Yang-Baxter equation:

- (as maps ).

A BD-law is a BCD-law if the multiplication on is "-commutative", meaning that

- (C)

- (as maps ).

Condition (B) is called a Yang-Baxter equation because it literally is the Yang-Baxter equation defined on monoid objects, when is viewed as a monoid in the category of endofunctors on .[4]

Entwining

For an algebra and a coalgebra over a shared field , an entwining between them is a linear map satisfying analogous conditions to those that would be required, were a distributive law. Specifically, the commutation diagram that would be induced by a hypothetical multiplication is replaced with one for induced by the comultiplication ; likewise, the triangle diagram is replaced with one of type , induced by the counit.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Toposes, Triples and Theories. Springer-Verlag. 1985. ISBN 0-387-96115-1. http://www.case.edu/artsci/math/wells/pub/pdf/ttt.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Beck, Jon (1969). "Distributive laws". Seminar on Triples and Categorical Homology Theory, ETH 1966/67. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. 80. pp. 119–140. doi:10.1007/BFb0083084. ISBN 978-3-540-04601-1.

- ↑ Distributive law in nLab

- ↑ Kasangian, Stefano; Lack, Stephen; Vitale, Enrico M. (2004-12-05), "Coalgebras, Braidings, and Distributive Laws", Theory and Applications of Categories 13: pp. 129-146, 2004-11-08, ISSN 1201-561X, https://www.emis.de/journals/TAC/volumes/13/8/13-08abs.html, retrieved 2025-09-04

- ↑ Brzeziński, T.; Majid, S. (1998). "Coalgebra Gauge Theory". Comm. Math. Phys. 191 (2): 467–492. doi:10.1007/s002200050274. Bibcode: 1998CMaPh.191..467B.

- Beck, Jon (1969). "Distributive laws". Seminar on Triples and Categorical Homology Theory, ETH 1966/67. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. 80. pp. 119–140. doi:10.1007/BFb0083084. ISBN 978-3-540-04601-1.

- Toposes, Triples and Theories. Springer-Verlag. 1985. ISBN 0-387-96115-1. http://www.case.edu/artsci/math/wells/pub/pdf/ttt.pdf.

- Distributive law in nLab

- Böhm, G. (2005). "Internal bialgebroids, entwining structures and corings". Algebraic Structures and Their Representations. Contemporary Mathematics. 376. pp. 207–226. ISBN 9780821836309.

- Brzeziński, T.; Majid, S. (1998). "Coalgebra bundles". Comm. Math. Phys. 191 (2): 467–492. doi:10.1007/s002200050274. Bibcode: 1998CMaPh.191..467B.

- Brzezinski, Tomasz; Wisbauer, Robert (2003). Corings and Comodules. London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series. 309. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53931-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ea1EeaOu_HUC&pg=PP1.

- Fox, T.F.; Markl, M. (1997). "Distributive laws, bialgebras, and cohomology". Operads: Proceedings of Renaissance Conferences. Contemporary Mathematics. 202. American Mathematical Society. pp. 167–205. ISBN 9780821805138.

- Lack, S. (2004). "Composing PROPS". Theory Appl. Categ. 13 (9): 147–163. http://www.tac.mta.ca/tac/volumes/13/9/13-09abs.html.

- Lack, S.; Street, R. (2002). "The formal theory of monads II". J. Pure Appl. Algebra 175 (1–3): 243–265. doi:10.1016/S0022-4049(02)00137-8.

- Markl, M. (1996). "Distributive laws and Koszulness". Annales de l'Institut Fourier 46 (2): 307–323. doi:10.5802/aif.1516.

- Street, R. (1972). "The formal theory of monads". J. Pure Appl. Alg. 2 (2): 149–168. doi:10.1016/0022-4049(72)90019-9.

- Škoda, Z. (2004). "Distributive laws for monoidal categories". arXiv:math/0406310.

- — (2007). "Equivariant monads and equivariant lifts versus a 2-category of distributive laws". arXiv:0707.1609 [math.CT].

- — (2008). "Bicategory of entwinings". arXiv:0805.4611 [math.RA].

- Wisbauer, R. (2008). "Algebras versus coalgebras". Appl. Categ. Structures 16 (1–2): 255–295. doi:10.1007/s10485-007-9076-5.

|