Earth:Biogeoclimatic ecosystem classification

Biogeoclimatic ecosystem classification (BEC)[1][2] is an ecological classification framework used in British Columbia to define, describe, and map ecosystem-based units at various scales, from broad, ecologically-based climatic regions down to local ecosystems or sites.[3][4] BEC is termed an ecosystem classification as the approach integrates site, soil, and vegetation characteristics to develop and characterize all units. BEC has a strong application focus[5] and guides to classification and management of forests, grasslands and wetlands are available for much of the province to aid in identification of the ecosystem units.

History

The biogeoclimatic ecosystem classification (BEC) system evolved from the work of Vladimir J. Krajina,[6] a Czech-trained professor of ecology and botany at the University of British Columbia and his students, from 1949 - 1970. Krajina conceptualized the biogeoclimatic approach[7] as an attempt to describe the ecologically diverse and largely undescribed landscape of British Columbia, the mountainous western-most province of Canada, using a unique blend of various contemporary traditions. These included the American tradition of community change and climax,[8] the state factor concept of Jenny,[9] the Braun-Blanquet approach,[10] the Russian biogeocoenose,[11] and environmental grids,[12] and the European microscopic pedology approach[13]

The biogeoclimatic approach was subsequently adopted by the Forest Service of British Columbia in 1976—initially as a five-year program to develop the classification to assist with tree species selection in reforestation. The classification concepts adopted from Krajina were modified by the staff of the B.C. Forest Service in the implementation of a provincial classification.[4] Over the past 40 years, the BEC approach has been expanded and applied to all regions of British Columbia. It has developed into a comprehensive framework for understanding ecosystems in a climatically and topographically complex region.

Classification Framework

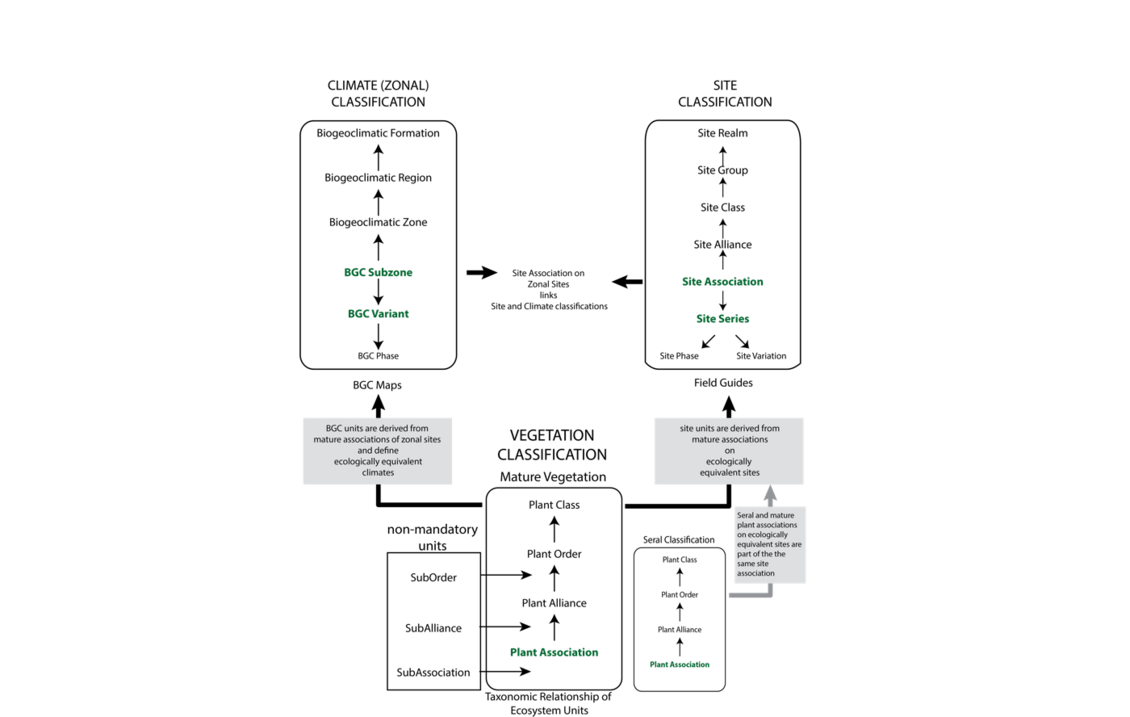

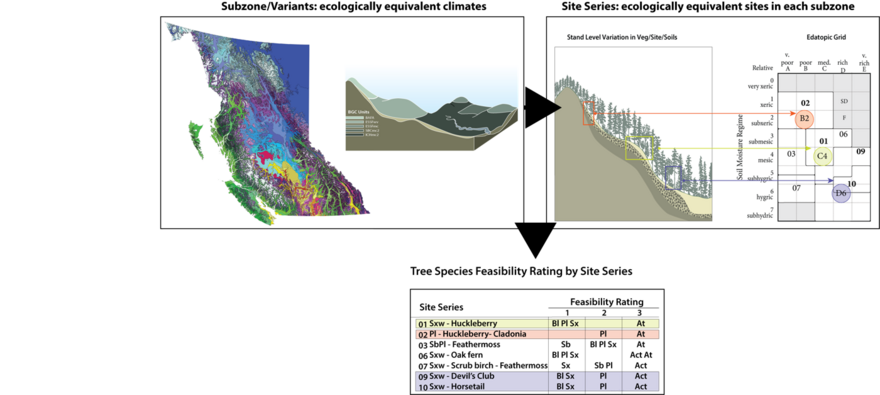

Biogeoclimatic ecosystem classification (BEC) is best described as a classification framework that leverages a modified Braun-Blanquet[14] vegetation classification approach to identify and delineate ecologically equivalent climatic regions and site conditions (Figure 1).

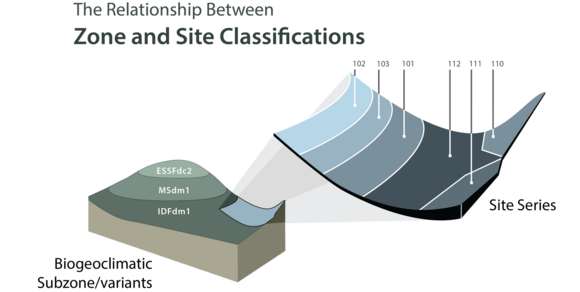

The framework[1][2] integrates vegetation classification with two other component hierarchical classifications: climate (or zonal) and site (Figure 2) where the vegetation classification hierarchy is used to develop the other two component hierarchies.

The emphasis of the approach is to create ecological units with similar site potential as reflected by mature or climax plant communities.

Vegetation Component

The BEC approach classifies vegetation in a hierarchy (see Figure 2) that presents vegetation communities at various levels of generalization. At upper levels of the hierarchy, the communities may have the same dominant tree species and occur in the same broad climate, for example, western redcedar - western hemlock forests of maritime climates of British Columbia. Whereas, at lower levels of the hierarchy, the communities will have very similar understorey species and will occur on similar site conditions, for example, western redcedar forests dominated by skunk cabbage (Lysitchiton americanum) occurring on wet, swampy sites.

Categories of the vegetation hierarchy are modelled after the Braun-Blanquet approach[15] including the class, order, alliance, and association levels. Subcategories are generally also applied (i.e., subassociation, suballiance, suborder). Fundamentally, the climax plant association is the basic unit of BEC. In the BEC approach, mature or climax plant associations of the zonal site define biogeoclimatic subzones and ecologically equivalent sites within a given biogeoclimatic unit are recognized and differentiated by mature or climax plant associations and used to define site units. The climax forest state is recognized where main canopy tree species are the same as those regenerating in the understory. Climax forests of British Columbia (BC) are most commonly dominated by shade-tolerant tree species; however, under some climates or site conditions, shade-intolerant species will regenerate under the canopy. For example, in the driest forested biogeoclimatic units of BC, several pine species that are considered seral species through most of their distribution regenerate under the forest canopy and are recognized as zonal climax species: lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) in the Sub-Boreal Pine Spruce [SBPS] zone and ponderosa pine (P. ponderosa) in the Ponderosa Pine [PP] zone.

Climate or Zonal Component

The BEC system classifies climates using a zonal site approach. The zonal site concept arose from the early works of the Russian soil scientist Vasily Dokuchaev (late 1800’s) and soil scientist/forester Georgy N. Vysotsky. They considered that sites and soils with average conditions best reflected the regional climate.[16] BEC adopted the zonal concept and developed specific site and soils criteria to define a zonal site.[2] The mature/climax plant association that occurs on zonal sites is termed the zonal plant association and is used to characterize, differentiate and map biogeoclimatic subzones (see Figure 2). In the climate component hierarchy, subzones are the fundamental unit, which are grouped into zones based largely on similarity of shade-tolerant (climax) tree species composition of the zonal plant association. Zonal plant orders characterize Biogeoclimatic Zones; zonal plant associations characterize Biogeoclimatic Subzones; and, zonal plant subassociations can be used to characterize Biogeoclimatic Variants.

Site Component

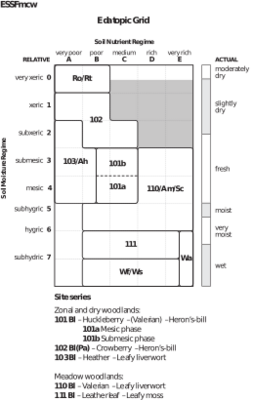

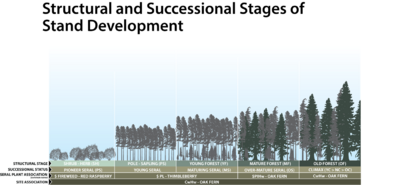

Plant associations and subassociations are similarly used to define zonal and azonal ecosystems on different site conditions within a consistent climate regime (biogeoclimatic subzone/variant). This approach emphasizes site conditions as the effects of climate regime are controlled. These biogeoclimatic and site specific ecosystem units are termed site series (see Figure 2). In the forested environments of BC, soil moisture and soil nutrient gradients are the primary site-level gradients. Soil moisture regime is strongly influenced by position on a slope (Figure 3). Soil moisture and soil nutrient regimes are the two categorical axes used in an edatopic grid to characterize the generalized environmental conditions of vegetation units within a biogeoclimatic unit for most types of terrestrial ecosystems (see Figure 4 for an example). Site series from different climates (biogeoclimatic units), which share the same mature or climax plant association, are said to occupy ecologically equivalent conditions and are combined into site associations. Site associations are similar in concept to forest site types of Cajander[17] and habitat types of the U.S. Pacific Northwest.[18] Where seral plant associations are defined, they are linked directly to the site series (Figure 5).

-

Figure 3. Relative soil moisture regime in relation to landscape position and geologic material

-

Figure 4. Edatopic grid for Engelmann Spruce - Subalpine Fir, moist cool woodland (ESSFmcw) subzone displaying site series and other vegetation by soil moisture and soil nutrient regimes. Site series with trees have three-digit number codes. Other codes are: Ro = Rock outcrop; Rt = talus; Ah = alpine heath; Am = Alpine meadow; Sc = Subalpine shrubland; Wf = Wetland fen; Ws = Wetland swamp; Wa = Alpine wetland. Tree species codes are: Bl - subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa); Pa - whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis)

-

Figure 5. Structural stages and seral plant associations for the CwHw - Oak fern Site Association. The CwHw - Oak fern plant association characterizes the range of site conditions included in the CwHw - Oak fern site association. This range of sites may support vegetation of various ages or stages of development. The stages can be characterized by Structural Stage categories, e.g., young forest, or by their Successional Status, e.g., maturing seral. The developing vegetation can also be classified into seral plant associations (designated with $ sign). Note: Tree species codes are: Cw = western redcedar; Hw = western hemlock; Pl = lodgepole pine.

Uses of BEC

The BEC system is used by resource managers in British Columbia to assist them with the management of natural ecosystems for forestry, conservation, and wildlife,[5] The system was initially developed to determine, on a site-specific basis, the ecologically suitable tree species for regeneration after forest harvesting.[19] It has evolved into a tool that is also used for:

- Setting standards for species selection and stocking after harvest[20]

- Setting conservation targets[21]

- Determining at-risk ecosystems[22]

- Understanding range management issues[23]

- Determining wildlife suitability and capability[5]

Figure 6 demonstrates how the BEC system is used to present ecologically suitable tree species for regeneration.[20]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mackenzie, William H.; Meidinger, Del (2018). "The Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification Approach: an ecological framework for vegetation classification". Phytocoenologia 48 (2): 203–213. doi:10.1127/phyto/2017/0160. https://www.schweizerbart.de/papers/phyto/detail/48/88305/The_Biogeoclimatic_Ecosystem_Classification_Approach_an_ecological_framework_for_vegetation_classification.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Pojar, J. (1987). "Biogeoclimatic Ecosystem Classification in British Columbia". Forest Ecology and Management 22 (1–2): 119–154. doi:10.1016/0378-1127(87)90100-9. https://www.journals.elsevier.com/forest-ecology-and-management.

- ↑ "BEC WEB". https://www.for.gov.bc.ca/hre/becweb/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Meidinger, D.V.; Pojar, J. (1991). Ecosystems of British Columbia. Special Report Series 6. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: B.C Ministry of Forests. ISBN 0-7718-8997-6.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 MacKinnon, A.; Meidinger, D.; Klinka, K. (1992). "Use of the biogeoclimatic ecosystem classification system in British Columbia". The Forestry Chronicle 68: 100–120. doi:10.5558/tfc68100-1.

- ↑ Drabek, J. (2012). Vladimir Krajina: World War II Hero and Ecology Pioneer. Vancouver, British Columbia: Ronsdale Press. ISBN 978-1-55380-147-4.

- ↑ Krajina, Vladimir (1969). "Ecology of forest trees in British Columbia". Ecology of Western North America 2 (1): 1–147.

- ↑ Clements, F.E. (1936). "Nature and Structure of the Climax". Journal of Ecology 24 (1): 252–284. doi:10.2307/2256278.

- ↑ Jenny, H. (1941). Factors of Soil Formation. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co.. ISBN 0-486-68128-9.

- ↑ Braun-Blanquet, J. (1932). Plant Sociology. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co..

- ↑ Sukachev, V.N. (1945). "Biogeocoenology and phytocoenology". Proc. USSR Acad. Sci. 47: 429–431.

- ↑ Pogrebnyak, P.S. (1955). Foundations of forest typology. Kiev: Academy of Science Ukraine Soviet Socialist Republic.

- ↑ Kubiena, W.L. (1938). Micropediology. Ames, Iowa, USA: Collegiate Press Inc..

- ↑ De Caceres, M.; Chytry, M.; Agrillo, E.; Attore, F.; Botta-Dukat, Z.; Capelo, J.; Czucz, B.; Dengler, J. et al. (2015). "A comparative framework for broad-scale plot-based vegetation classification". Applied Vegetation Science 18 (4): 543–560. doi:10.1111/avsc.12179.

- ↑ Van Der Maarel, E. (1975). "The Braun-Blanquet Approach In Perspective". Vegetatio 30 (3): 213–219. doi:10.1007/BF02389711.

- ↑ Ponomarenko, Serguei; Alvo, Rob (2001). Perspectives on developing a Canadian classification of ecological communities. Information report. ST-X series1192-1064ST-X-18. Ottawa, Canada: Natural Resources Canada. ISBN 0-662-29816-0.

- ↑ Cajander, A.K. (1949). "Forest types and their significance". Acta Forestalia Fennica 56 (5): 1–71. doi:10.14214/aff.7396.

- ↑ Pfister, Robert D.; Kovalchik, Bernard L.; Arno, Stephen F.; Presby, Richard C. (1977). Forest Habitat Types of Montana. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-GTR-34. Ogden, Utah: US Department of Agriculture Forest Service.

- ↑ Green, R.N.; Klinka, K. (1994). A Field guide for site identification and interpretation for the Vancouver Forest Region.. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Forests, Research Program. ISBN 0-7726-2129-2. OCLC 933080934. http://worldcat.org/oclc/933080934.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ministry of Forests, Lands. "Stocking Standards - Province of British Columbia". https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/forestry/managing-our-forest-resources/silviculture/stocking-standards.

- ↑ Price, Karen; Holt, Rachel F.; Daust, Dave (May 2021). "Conflicting portrayals of remaining old growth: the British Columbia case" (in en). Canadian Journal of Forest Research 51 (5): 742–752. doi:10.1139/cjfr-2020-0453. ISSN 0045-5067.

- ↑ Ministry of Environment and Climate Change. "B.C. Conservation Data Centre - Province of British Columbia". https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/plants-animals-ecosystems/conservation-data-centre.

- ↑ Steen, O.A.; Coupe, R.A. (1997). A field guide to forest site identification and interpretation for the Cariboo Forest Region. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Forests, Research Branch. ISBN 0-7726-3495-5. OCLC 44393854. http://worldcat.org/oclc/44393854.

|