Earth:Corycian Cave

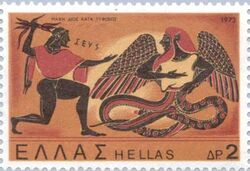

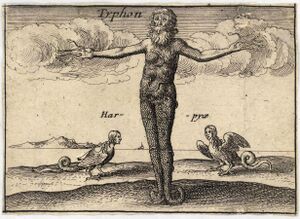

The Corycian Cave (/kəˈrɪʃən/; Greek: Κωρύκιον ἄντρον, romanized: Kōrykion antron)[1] is located in central Greece on the southern slopes of Mount Parnassus, in Parnassus National Park, which is situated north of Delphi. The Corycian Cave has been a sacred space since the Neolithic era, and its name comes from the mythological nature spirits the Corycian nymphs, which were depicted as looking like beautiful maidens and were said to inhabit the cave. More specifically it is named after the nymph Corycia; however, its name etymologically derives from korykos, "knapsack". A modern name for the cave in some references is Sarantavli, meaning "forty rooms" due to the fact that the cave has many caverns that go deep into Mt. Parnassus. The Corycian Cave was used primarily as a place of worship for the Pan, the god of the wild, as well as the Corycian nymphs, Zeus, and is also thought to be the ritual home of Dionysus.[2] Also in mythology, Zeus was imprisoned in the Corycian Cave by the monster Typhon.

Today, the Corycian Cave is a notable tourist attraction for those who travel to Delphi. Tourists often hike past the Corycian Cave as they travel on ancient trails up Mt. Parnassus to have a much broader view of the landscape of the Livadi Valley below.

In modern times, the cave has been a place of refuge for the surrounding population during foreign invasions e.g. from the Persians (Herodotus, 8.36) in the 5th century BC, the Turks during the Greek War of Independence, and from the Germans in 1943.

Location and geography

Exterior geography

According to author Jeremy McInerney, "Delphi and Mt.Parnassus became, through myth and ritual, landscape in which tensions between wilderness and civilizations... could be narrated, enacted, and organized". This could be seen in the ritual and in topography where Mt.Parnassus is split into the zones of harsh wilderness at its peaks in contrast to the plateau below that was used for cultivation, and in the center of this, as McInerney says, "... the deeper movement from chaos to order..."[3] was the Corycian Cave. Due to its topographical location, to ancient Greeks the Corycian Cave was the divider between wilderness and culture. It represents a place outside of the sanctuary of Delphi below but not at the dangerous mountain peaks, a place where for mythological purposes, "... where nymphs are possessed and tamed by the gods..."[3]

The Corycian Cave sits at an altitude of 1,250m above sea level. The ascent to the Corycian Cave from the plateau below was a steep and rocky one, climbing an elevation of 1,000m in under a half kilometer.

Interior geography

Corycian Cave is the largest cave in the Delphi region.[4] Some ancient texts describe Corycian Cave as being located in, "…a large oval depression with high rocky walls, where the best saffron grew; it was filled with an agreeable, shady woodland…and at the bottom there opened an underground cavern."[5] It is thought that the cave was formed after the collapse of an older cave system, possible due to an earthquake.[5] The composition of Corycian Cave itself mostly consists of limestone and schist plaques—as is common of the many caves throughout the Delphi region. The structure of Corycian Cave is made up of two central caverns and then gets narrower as it extends deeper.[4] The length and width of the first chamber is roughly 90x60 meters and the height is roughly 50 meters. The chamber is also filled with stalactites and stalagmites formed out of limestone. One prominent stalagmite in particular known as Table has a relatively large, flat top that was used a depository for votives by worshipers.[4]

Cave exploration and archaeology

Artifacts found

The Corycian Cave was excavated in 1969 by French hellenist Pierre Amandry and his team from the French School of Athens. During the excavation they found many artifacts and vessels left by ancient worshippers. The majority of objects found were made out of livestock bone. This included 22,000 astragals, which were primarily from sheep and goats, that were made out of talus, a large bone that protrudes from the ankle. The astragals were believed to be primarily used in games of chance, similar to the modern day dice. Of the 22,000 found, 2,500 were found to have been purposefully smoothed down and pierced so that a leather thread could go through them to form a necklace (36 were set in lead and 2 in gold). Also in the Corycian Cave, archeologists found a variety of rings, bronze figurines, ceramics, metal objects, as well as several wind instruments such as the auloi.[6]

Although there were some instances in the cave where gold was found, the most common vessels found were that of bone of deer, sheep, and goat. Artifacts found at the Corycian Cave point to the majority of worshippers being shepherds, goatherds, and hunters due to the lack of more expensive gifts left at the cave.

As a sanctuary space

History of use

The earliest evidence of human inhabitance in Corycian Cave dates back to the Neolithic period—around 4000 years BCE.[7] Corycian Cave was used off and on over the course of history rather than continuously. Some of the earliest evidence of worship at Corycian Cave is from hunters and shepherds during the later Neolithic period.[6] During the Greek-Persian Wars (499–448 BCE), the inhabitants of ancient Delphi used Corycian Cave as a place to hide from Persian invaders.[6]

Worshiper demographics

Archeological evidence from Corycian Cave suggests that the majority of worshipers were humble, ordinary people rather than wealthy or powerful people.[9] Many of the worshipers at Corycian Cave are thought to have been shepherds or hunters who lived and worked around Mount Parnassus.[10] There is also evidence of women and children worshipping at Corycian Cave. Corycian Cave was also popular among worshipers belonging to the cult of Pan due to the cave's mythological associations with the god. Most votives left inside Corycian Cave by worshipers were made of clay or bone.[10] The major city of ancient Delphi was in relatively close proximity to Corycian Cave. As a result, those who traveled from other places to see the monuments of Delphi would occasionally stop by Corycian Cave and leave small votives.[10]

Worshiper experience

The ancient geographer Pomponius Mela referenced his experience at Corycian Cave in his writing. An article by George C. Boon referencing Mela's work reads," 'It terrifies those entering by the sound of cymbals clashing by divine agency and with a great din…Within is a space greater than anyone has ventured to cross, so dreadful it is, and on that account is unknown.' "[5] Mela's work, as referenced by Boon, suggests that worshipers visiting Corycian Cave may feel fear due to the loud noises, darkness, and vastness of the space.[5] Worshipers also would have seen water dripping from the ceiling and oozing out of the ground, which gave Corycian Cave a sparkling appearance in areas where light was present.[11] Ancient worshipers also believed that an inner cavern of Corycian Cave was the home of the mythological monster Typhon. A shrine to Poseidon was located near the entrance to Typhon's lair, and worshipers felt that this would prevent the monster from escaping and wreaking havoc.[5] Aside from feelings of fear, Mela also described Corycian Cave as feeling very impressive and awe inspiring. There were also reports of smoke being seen coming out of Corycian Cave, which led worshipers to believe that the cave indeed housed some deities.[5]

In ancient Greek sources

In ancient times, Corycian Cave was used as a sanctuary since at least 4000 B.C.E.[7] The Corycian Cave also showed up in several other ancient Greek sources: Strabo, in his Geography, writes:

The whole of Parnassos [Mountain in Phokis] is esteemed as sacred [to Apollon], since it has caves and other places that are held in honor and deemed holy. Of these the best known and most beautiful is Korykion, a cave of the Nymphai bearing the same name as that in Kilikia [in Asia Minor]. (9.3.1)

Pausanias in his Guide to Greece writes:

On the way from Delphi to the summit of Parnassus, about sixty stades distant from Delphi, there is a bronze image. The ascent to the Corycian cave is easier for an active walker than it is for mules or horses. I mentioned a little earlier in my narrative that this cave was named after a nymph called Corycia, and of all the caves I have ever seen this seemed to me the best worth seeing.... But the Corycian cave exceeds in size those I have mentioned, and it is possible to make one's way through the greater part of it even without lights. The roof stands at a sufficient height from the floor, and water, rising in part from springs but still more dripping from the roof, has made clearly visible the marks of drops on the floor throughout the cave. The dwellers around Parnassus believe it to be sacred to the Corycian nymphs, and especially to Pan. (10.32.2–7)

In Pseudo-Apollodorus’ Bibliotheca, the cave is mentioned when Zeus fights the monster Typhon. In this account, After Typhon steals Zeus’ sinews, he places Zeus in the Corycian cave:

However Zeus pelted Typhon at a distance with thunderbolts, and at close quarters struck him down with an adamantine sickle, and as he fled pursued him closely as far as Mount Casius, which overhangs Syria. There, seeing the monster sore wounded, he grappled with him. But Typhon twined about him and gripped him in his coils, and wresting the sickle from him severed the sinews of his hands and feet, and lifting him on his shoulders carried him through the sea to Cilicia and deposited him on arrival in the Corycian cave. (1.6.3)

In mythology

Corycian nymphs

The Corycian nymphs are a mythological group of three sisters who live on Mount Parnassus, and they are the daughters of Pleistus—a river god. The Corycian nymphs are Corycia, Melaina, and Kleodora. Corycia is known for being the namesake of Corycian Cave, and she is also said to have a child, named Lycorus, with the god Apollo. Melaina is also believed by some to have bore one of Apollo's children named Delphos—after whom the city of Delphi was said to be named. Kleodora is known for bearing her son, Parnassus, with the god Poseidon. Parnassus is said to be the namesake of Mount Parnassus.[12] In ancient times there was a tradition of worshiping nymphs in caves that housed natural springs, and the Corycian nymphs were also worshiped as part of this tradition. Additionally, the Corycian nymphs are often associated with Apollo. When Apollo killed Delphyne (a monster) near Mount Parnassus, it was said that the Corycian nymphs shouted to support the god and give him strength.[9] Aided by the intercession of the Corycian Nymphs during his battle with Delphyne, Apollo was able to achieve the power of divination.[4]

Pan

After the Battle of Marathon (490) Pan replaced Hermes as the god most associated with nymphs—including the Corycian Nymphs in Corycian Cave.[9] Due to this association, Pan became regularly worshiped at Corycian Cave.[9] Those who lived near Mount Parnassus regarded Pan as the guardian of Corycian Cave.[12] Many of those who lived and worked around Mount Parnassus were hunters or shepherds, and Pan is associated with these professions.[10] Many of the votives and artifacts found in Corycian Cave can be tied to the cult of Pan.[5] There is also epigraphic evidence of worship to Pan, as he is mentioned in inscriptions carved into one of the Walls in Corycian Cave.[13] Pan is also involved in an ancient ritual in which a shepherd will dress up as Pan and hunt for fish, and the fish will later be sacrificed to Pan after they are caught. This ritual is associated with Pan's involvement in the mythic battle between Zeus and Typhon—which culminated in Typhon being banished to Corycian Cave.[13]

Zeus

The Corycian Cave plays a key role in the mythological battle between Zeus and Typhon. Typhon was a mythological beast, born of Earth and Tartarus and he battled the gods, most notably Zeus. During their battle, Zeus and Typhon fought back and forth, Zeus throwing his lightning bolts, eventually injuring Typhon. However, Typhon also injured Zeus and was able to bring him, and imprison him in the Corycian Cave. Typhon had the cave guarded by the she-dragon Delphyne. Still however, Hermes and Aegipan were able to free Zeus and he went on to defeat Typhon. The Corycian Cave played a key role in the Greek mythological battles with the gods, and because Zeus was said to have been imprisoned in the cave, he was also worshipped there.[14]

Dionysus

While the connection to the Corycian nymphs and Pan are well established as they are mentioned in the nine inscriptions found at the cave as well in Pausanias,[15] the connection to Dionysus is not as clear-cut. One of the inscriptions, which has been severely eroded by weathering, seems to say that Thyiades participated in ceremonies at the Corycian Cave. Also, when looking at Aeschylus’ work, the Eumenides, there seems to be a clear connection set up between Dionysus and the Corycian Cave.[15] Additionally, in Pausanias’ Guide to Greece, when referring to the location of the Corycian Cave, Pausanias goes on to then describe the heights of Mount Parnassus and reveals to the reader that Thyiades raved there.[16] Despite the wild raves taking place on top of the mountain as opposed to the cave, a clear connection between the surrounding area of the Corycian Cave and the Cult of Dionysus can still be seen. Further evidence for the connection between Dionysus and the Corycian Cave stems from Pan being often depicted in scenes with Dionysus, hinting at a connection between the two gods.[17]

Finally, it is thought that the Corycian Cave is the place of residence of Dionysus, just as Apollo’s residence is Delphi. In the wintertime, when Apollo leaves Delphi, Dionysus comes down from the cave and occupies Apollo’s place in Delphi. This transition process involved the maidens of Delphi (assumed to be Thyiades) being sent to the cave and then help escort the god into the sanctuary and honor Dionysus in Apollo’s Temple.[18]

References

- ↑ Κωρύκιον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ McInerney (1997), p. 281.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wright, John Henry (1906). "The Origin of Plato's Cave". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 17: 131–142. doi:10.2307/310313. https://www.jstor.org/stable/310313. Retrieved 2021-12-02.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Parnassus and the Corycian Cave - Archaeological Site of Delphi" (in en-US). https://delphi.culture.gr/parnassos/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Boon, George C. (1976). "Clement of Alexandria, Wookey Hole, and the Corycian Cave". Proceedings of the University of Bristol Spelæological Society 14: 131–140. http://www.ubss.org.uk/resources/proceedings/vol14/UBSS_Proc_14_2_131-140.pdf.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 McInerney (1997), pp. 263–283.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Liritzis, Ioannis; Aravantinos, Vassilios; Polymeris, George S.; Zacharias, Nikolaos; Fappas, Ioannis; Agiamarniotis, George; Sfampa, Ioanna K.; Vafiadou, Asimina et al. (2015-04-01). "Witnessing prehistoric Delphi by luminescence dating" (in en). Comptes Rendus Palevol 14 (3): 219–232. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2014.12.007.

- ↑ "Parnassus and the Corycian Cave - Archaeological Site of Delphi" (in en-US). https://delphi.culture.gr/parnassos/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Larson, Jennifer (1995). "The Corycian nymphs and the bee maidens of the Homeric Hymn to Hermes". Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 36: 341–357. https://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/viewFile/2961/5819.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Volioti, Katerina (2011-10-30). "Travel tokens to the Korykian Cave near Delphi: Perspectives from material and human mobility" (in en). Pallas 86 (86): 263–285. doi:10.4000/pallas.2188. https://journals.openedition.org/pallas/2188.

- ↑ Bowe, Patrick (2013–2014). "The garden grotto: its origin in the ancient Greek perception of the natural cave". Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes 33 (2): 128. doi:10.1080/14601176.2013.807077. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/14601176.2013.807077.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "CORYCIAN NYMPHS (Nymphai Korykiai) - Delphian Naiad Nymphs of Greek Mythology". https://www.theoi.com/Nymphe/NymphaiKorykiai.html.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lytle, Ephraim (2011). "The Strange Love of the Fish and the Goat: Regional Contexts and Rough Cilician Religion in Oppian's "Halieutica" 4.308-73". Transactions of the American Philological Association 141 (2): 333–386. doi:10.1353/apa.2011.0010. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41289748.

- ↑ "APOLLODORUS, THE LIBRARY BOOK 1 - Theoi Classical Texts Library". https://www.theoi.com/Text/Apollodorus1.html.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 McInerney (1997), p. 278.

- ↑ Pausanias. "Pausanias: 10.32-38". Theoi Classical Texts Library. https://www.theoi.com/Text/Pausanias10C.html#1.

- ↑ "Pan-Greek God of Shepherds, Hunters, and the Wilds". Theoi Classical Texts Library. https://www.theoi.com/Georgikos/Pan.html.

- ↑ McInerney (1997), pp. 279–281.

- McInerney, Jeremy (1997). "Parnassus, Delphi, and the Thyiades". Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 38 (3): 279–283. https://grbs.library.duke.edu/article/view/2611/5887.

External links

- Κωρύκιο Άντρο Korykio Antro or Pan's Cave

- Korykian Cave in the Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites

- Michael Scott. Delphi: The Bellybutton of the Ancient World. BBC 4. 10:48 minutes in. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Corycian Cave Path to Corycian Cave

[ ⚑ ] 38°30′54″N 22°31′14″E / 38.515°N 22.52056°E

|