Earth:Dispersive body waves

Dispersive body waves is an important aspect of seismic theory. When a wave propagates through subsurface materials both energy dissipation and velocity dispersion takes place. Energy dissipation is frequency dependent and causes decreased resolution of the seismic images when recorded in seismic prospecting. The attendant dispersion is a necessary consequence of the energy dissipation and causes the high frequency waves to travel faster than the low-frequency waves. The consequence for the seismic image is a frequency dependent time-shift of the data, and so correct timings for lithological identification cannot be obtained.

Basics

When we know the energy dissipation (attenuation), we can calculate the time shift due to dispersion because there is a relation between attenuation and the dispersion in a seismic media. Dispersion equations are obtained from the application of an integral transform in the frequency domain that are of the Kramers-Krönig type. This effect is described in the article ‘Dispersive body waves’ by Futterman (1962).[1]

For a better understanding of dispersion waves in seismic medias I would recommend the book 'Seismic inverse Q-filtering' by Yanghua Wang (2008). He discusses the theory of Futterman and starts with the wave equation:[2]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac { dU(r,w)}{ dr} - ikU(r,w)=0 \quad (1.1) }[/math]

where U(r,w) is the plane wave of radial frequency w at travel distance r, k is the wavenumber and i is the imaginary unit. Reflection seismograms record the reflection wave along the propagation path r from the source to reflector and back to the surface.

Equation (1.1) has an analytical solution given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ U(r+\bigtriangleup r,w) =U(r,w)\exp (ik\bigtriangleup r) \quad (1.2) }[/math]

Where k is the wave number. When the wave propagates in inhomogeneous seismic media the propagation constant k must be a complex value that includes not only an imaginary part, the frequency-dependent attenuation coefficient, but also a real part, the dispersive wavenumber. We can call this K(w) a propagation constant in line with Futterman.[3]

- [math]\displaystyle{ K(iw) =k(w)+ i a(w) \quad (1.3) }[/math]

Here a(w) is taken positive to assure that energy is lost from the wave to the medium. Now when K(w) are separated into a real part for attenuation and an imaginary part for dispersion, we can introduce the Kramer-Krönig relation by a Hilbert transform H of the attenuation a(w):

- [math]\displaystyle{ K(iw) = H(a(w))+ i a(w) \quad (1.4) }[/math]

For our calculations to be valid we must make two assumptions: (a) the absorption coefficient a(w) is strictly linear in the frequency, over the range of measurement. We can call it bw. (b)The wave motion is linear i.e. the principle of superposition is valid. The second assumption is of more fundamental nature, and give us a possibility to express any pulse U as a superposition of plane waves.[3] The reason why Futterman introduced the Hilbert transform was to impose causality on the wave pulse.

Substituting this complex-valued wavenumber K(w) into solution (1.2) produces the following expression:

- [math]\displaystyle{ U(r+\bigtriangleup r,w)=U(r,w)\exp([-bw+ iH(bw)]\bigtriangleup r ) \quad (1.5) }[/math]

For a solution consistent with Futterman we can replace U(r,w) with the expression:

- [math]\displaystyle{ U(r,w) = U_0 exp(iwt) \quad (1.6) }[/math]

We can replace the distance increment ∆r by traveltime increment ∆t = ∆r/c. Here c is a constant. We can replace U0 with U' for correct scaling and equation (1.5) is expressed as

- [math]\displaystyle{ U(t+\bigtriangleup t,w)=U' exp(iw\bigtriangleup t)\exp([-bw+ iH(bw)]\bigtriangleup t) \quad (1.7) }[/math]

The sum of these plane waves gives the time-domain seismic signal,

- [math]\displaystyle{ U(t+\bigtriangleup t) =\int_0^\infty U(t+\bigtriangleup t,w)dw.\quad (1.8) }[/math]

Calculations

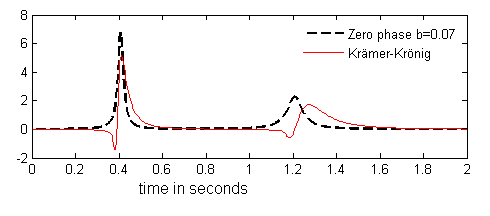

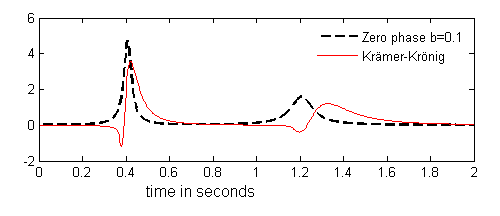

Some solutions of (1.7) (1.8) are plotted here. The dispersion of Kramer-Krönig type is visible in the way that the wave moves to the right compared to a solution with no dispersion (Forward zero phase solution). This assures us that we always get a causal wave solution with the Kramer - Krönig relation. The time shift correction due to dispersion can be found from the difference between the center of the zero-phase pulse and the center of the dispersed pulse. Upper graph is from attenuation b=0.07. Lower graph with b=0.1. The time shift increase with increased attenuation.

Inverse filtering

In seismic processing, in most applications, we do not go in the forward direction as above. So the theory of dispersive body waves has most applications in the theory of seismic inverse Q filtering. From the Wikipedia article on this subject we get the inverse Q-filter:

- [math]\displaystyle{ U(t+\bigtriangleup t,w)=U(t,w)\exp \bigg(|\frac{w}{w_h}|^{-\gamma} \frac{|w|\bigtriangleup t}{2Q(w)}\bigg) \exp \bigg( i|\frac{w}{w_h}|^{-\gamma} w\bigtriangleup t\bigg) \quad (1.8.a) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma =(\pi Q_r)^{-1} }[/math]

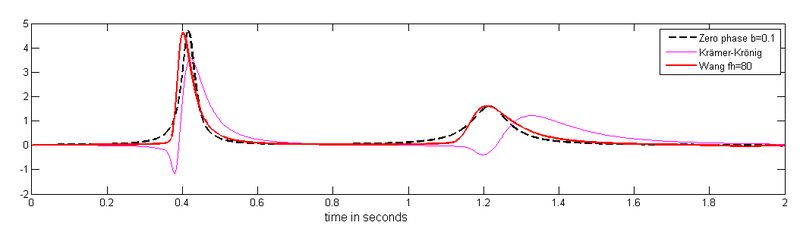

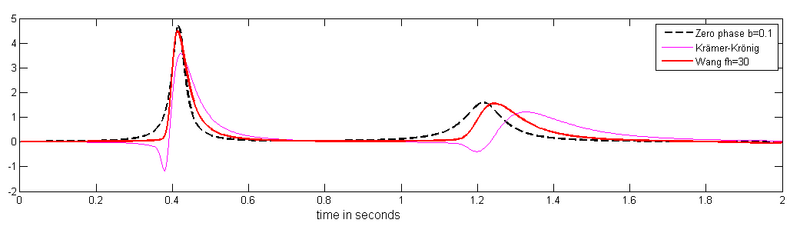

We take the phase only inversion procedure outlined in [4] and apply the phase part of (1.8.a), the second exponential, on the solution with b=0.1. Trial and error gave us a good inversion where the phase effect of the earth filter (introduced by the Kramer-Kronig relation - magenta on fig.2) was well corrected for with a reference frequency [5] fh=80 Hz (wh=2 π fh). We can see that the red graph on figure 2 is much like the black graph representing a zero-phase (non-dispersive) solution. A more used reference frequency is fh=30 Hz. On fig.2.b. we can see that this choice of reference frequency gives a solution that is more like a causal solution than for fig.2.a.

Discussion

Both the forward filter method equation (1.7) and the equation (1.8.a) are linked to the field of inverse Q filtering. A deeper study of (1.7) can be found in Aki, K, and Richards, P.G. (2002).[6] In (1.8.a) γ is a function of Q, and in (1.7) the constant b is linked to Q with the equation:

- [math]\displaystyle{ b = ( \frac{1}{2Q}) }[/math]

This relation is found in Aki, K and Richards [7]

In the outline above the method of Wang is used in seismic inverse Q filtering, and the Kramer-Krönig relation is used in the forward Q-filtering to create benchmark data for the inverse filtering. However, it is also possible to develop an inverse Q filter from the forward filter (1.7). This filter was developed by Hale D. (1981).[8] This filter was further studied by Gelius (1987) [9] In an article that is available on internet [10] written by Montana and Margrave - Crewes research report volume 16 (2004) - Hale’s inverse Q filter is compared with the inverse filter of Wang. They also compared with a third method, but this is not discussed here. The inversion method of Wang was by far the best method for phase correction.

Notes

- ↑ Futterman (1962) ‘Dispersive body waves’. Journal of Geophysical Research 67. p.5279-91

- ↑ Wang 2008, p. 60

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Futterman (1962) p.5280

- ↑ Wang 2008 p.86

- ↑ Wang 2008 p.20

- ↑ Aki, K, and Richards, P.G. 2002, Quantitative Seismology, theory and methods, University Science books

- ↑ Aki, K, and Richards p.166

- ↑ Hale, D, 1981 An inverse Q filter: SEP report 26.

- ↑ Gelius L.J. 1987. Inverse Q filtering: a spectral balancing technique. Geophysical Prospecting 35, 656-67.

- ↑ http://crewes.org/ForOurSponsors/ResearchReports/2004/2004-30.pdf [bare URL PDF]

References

- Wang, Yanghua (2008). Seismic inverse Q filtering. Blackwell Pub.. ISBN 978-1-4051-8540-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=IpwAjT-F_TgC.

- Futterman (1962) ‘Dispersive body waves’. Journal of Geophysical Research 67. p. 5279-91

|