Earth:East Australian Current

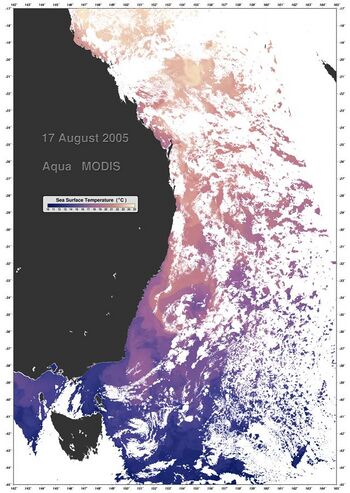

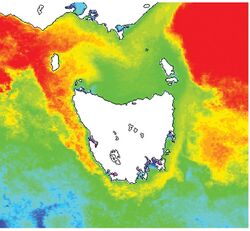

The East Australian Current (EAC) is the southward western boundary current that is formed from the South Equatorial Current (SEC) crossing the Coral Sea and reaching the eastern coast of Australia . At around 15° S near the Australian coast the SEC divides forming the southward flow of the EAC. It is the largest ocean current close to the shores of Australia. The EAC reaches a maximum velocity at 30° S where its flow can reach 90 cm/s. As it flows southward it splits from the coast at around 31° to 32° S. By the time it reaches 33° S it begins to undergo a southward meander while another portion of the transport turns back northward in a tight recirculation. At this location the EAC reaches its maximum transport of nearly 35 Sv (35 billion liters per second).[1] The majority of the EAC flow that does not recirculate will move eastward into the Tasman Front crossing the Tasman Sea just north of the cape of New Zealand. The remaining will flow south on the EAC Extension until it reaches the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. The Tasman Front transport is estimated at 13 Sv. The eastward movement of the EAC through the Tasman Front and reattaching to the coastline of New Zealand forms the East Auckland Current.[1][2] The EAC also acts to transport tropical marine fauna to habitats in sub-tropical regions along the south east Australian coast.

Physical Oceanography

The EAC is a surface current driven by winds over the South Pacific. During different parts of the year these winds control how the current behaves. The EAC starts on the west edge of the South Pacific gyre where it collects warm, nutrient poor water. As it skirts along the East Coast of Australia it carries a large amount of warm tropical water from the equator southward. This process is part of what allows the Great Barrier Reef to thrive, it keeps the east coast of Australia around 18 °C year round instead of dropping to 12 °C in the winter.[3]

The current is very low in nutrients, however, it remains important for the marine ecosystem. The EAC removes heat from the tropics and releases it to the mid-latitude water and atmosphere.[4] It does this by producing warm core eddies, which allow the Tasman Seas to have a large biodiversity.[5] The most southern tip of the EAC can produce these Eddies by wind currents. As instabilities in the current develop due to a westward Tasman Front, the meander pinches off to form eddies at a rate of once or twice per year.[6]

The EAC has nutrient poor water, however it does cause upwelling in places along the coast line.[7] The Eddies produced cause an increase in vertical mixing within the Tasman Sea. The process of producing, moving, and destroying eddies causes the thermocline layer to mix with the surface layer, bringing some nutrients up to the surface. The EAC and its eddies frequently flow onto the continental shelf and inshore, influencing circulation patterns and increasing mixing. Eddies aren't the only way the EAC brings nutrients to the surface. Features along the coast push the current further off shore and if there is a strong northerly wind, it will push the current even further off shore, allowing deep water to rise up the coast, bringing nutrients up to the surface.

The EAC experiences seasonal variations. It tends to be strongest in the summer, with an amplitude flow around 36.3 Sv. It is its weakest during the winter months flowing at a rate around 27.4 Sv.[6] Over the past 50–60 years the EAC has shifted. The south Tasman Sea has become warmer and saltier from 1944–2002. This has resulted in the current strengthening and extending southward. This shift in the EAC flow past Tasmania is controlled the Southern Hemisphere subtropical ocean circulation. This trend is thought to be caused by changes in wind patterns due to ozone depletion over Australia. There is a strong consensus with climate models that this trend will continue to intensify and accelerate over the next 100 years. The current is predicted to increase greater than 20%, thanks to the increase in South Pacific winds.[7]

In popular culture

In the 2003 Disney/Pixar animated film Finding Nemo, the EAC is portrayed as a superhighway that fish and sea turtles use to travel down the east coast of Australia. The characters Marlin (Albert Brooks) and Dory (Ellen DeGeneres) join Crush (Andrew Stanton), Squirt (Nicholas Bird) and a group of baby and adult sea turtles in using the EAC to help them travel to Sydney Harbour. The basic premise of the storyline is actually correct. Every summer, thousands of fish are swept from the Great Barrier Reef to Sydney Harbour and further south,[8] however, the Current is not nearly as rapid as depicted in the film.

See also

- Ocean current

- Oceanic gyres

- Physical oceanography

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Talley, Lynne. Descriptive physical oceanography: an introduction (6th ed.). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Inc.

- ↑ Roemmich, D.; Sutton, P. (1998). "The mean and variability of ocean circulation past northern New Zealand: Determining the representativeness of hydrographic climatologies.". J. Geophys. Res. 103: 13041–13054. doi:10.1029/98jc00583.

- ↑ "Ocean currents" (in en-AU). 2005-09-08. http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2005/09/08/2043133.htm.

- ↑ Roemmich, D.; Gilson, J.; Davis, R.; Sutton, P.; Wijffels, S.; Riser, S. (2007-02-01). "Decadal Spinup of the South Pacific Subtropical Gyre". Journal of Physical Oceanography 37 (2): 162–173. doi:10.1175/JPO3004.1. ISSN 0022-3670.

- ↑ Gold Coast City Council (2017-04-18). "The East Australian Current". https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/.../East-Australian-Current.pdf.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ridgway, K. R.; Godfrey, J. S. (1997-10-15). "Seasonal cycle of the East Australian Current" (in en). Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 102 (C10): 22921–22936. doi:10.1029/97JC00227. ISSN 2156-2202.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ridgway, Ken. "Marine Climate Change in Australia. The East Australian Current" (in en-US). http://oceanclimatechange.org/.

- ↑ Looking For Nemo, 2004-06-03, Catalyst, ABC

External links

- Image of the East Australian Current.

- Sea surface temperature and currents, New South Wales. (These Australian Bureau of Meteorology images form a seven-day loop, showing clearly both the sea surface temperatures and the movement of the East Australian Current)