Earth:Land registry of Bertier de Sauvigny

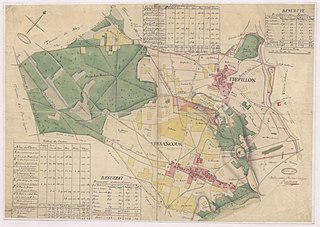

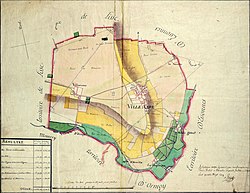

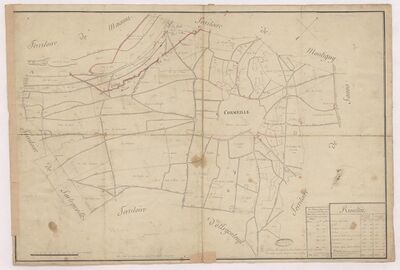

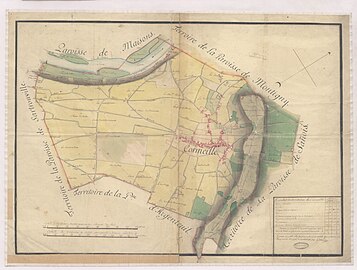

The land registry of Bertier de Sauvigny is a series of maps of the parishes of the generality of Paris surveyed from 1776 to 1791, often referred to as plans d'intendance. Bertier de Sauvigny, Intendant of Paris, sought to distribute taxes more equitably, by assessing the overall revenues of each parish. This cadastre was not yet drawn up by parcel, but by large masses of crops within each parish, because the parish was the geographical level for distributing the taille, in a country of personal size, and this choice was also quicker and met with less opposition.

Surveying work was carried out parish by parish by professional, often local, surveyors. The work was supervised by the intendant's subdelegates. Surveyors were small, relatively low-paid office-holders, often working with their families, whose training was essentially practical and empirical. They were coordinated by Pierre Dubray, the intendant's geographer and surveyor.

The surveyor identified the boundaries of the parish to be surveyed. He then measured the surfaces by large masses of crops, by triangulation, essentially using a gunter's chain, a try square and Pythagoras' theorem for his calculations. Measurements were expressed in local units and in king's arpents. They were recorded in a procès-verbal, which was used to draw up a plan. The whole was sent to the intendant, and the surveyor was paid if the work was judged to have been well done. He often exceeded the one-month deadline. In all, the project took 15 years to complete, but most of the work was carried out between 1783 and 1788. There was little opposition.

This land register probably inspired the first Napoleonic cadastre, which was also drawn up by crop mass. Certain figures were copied from one cadastre to the other. Area comparisons show the accuracy of Bertier de Sauvigny's measurements.

Today, the surveys and plans from this cadastre are preserved in the repositories of the departmental archives, under the name of plans d'intendance, and are sometimes accessible online. They constitute first-rate historical sources, used for studies on a wide range of subjects.

The need for a land registry

Fiscal concerns

The cadastre of Bertier de Sauvigny was produced between 1776 and 1791, under the authority of Louis Bénigne Bertier de Sauvigny, Intendant of the Generality of Paris.[To 1] It was a survey of the landscape of the generality of Paris, carried out as part of a tax reform, the tarification of the taille, pursued by successive Intendants of Paris, Louis Jean Bertier de Sauvigny and then his son Louis Bénigne Bertier de Sauvigny.[1] With the creation of this land register, Bertier de Sauvigny sought to gain a better understanding of the agricultural potential of each parish, in order to obtain a better return on the tax by distributing it fairly.[To 1]

It also responded to a preoccupation with territorial inventory that was spreading throughout the monarchical administrative apparatus.[To 1] At the same time, the idea that mathematical accuracy and tax fairness should go hand in hand was gaining ground in society.[2] This project was part of the modernization drive that swept through the Ancien Régime in the second half of the eighteenth century, a period during which various administrative and fiscal reforms were attempted, often with little success.[3] Bertier de Sauvigny achieved concrete results: the establishment of the average value of land in each parish and a theoretical tax rate for each farm.[To 2]

A cadastre for each crop mass

The cadastre drawn up under his authority did not represent individual land lots, but instead took a survey by mass of crops (vines, fields, pastures, etc.) for the entire parish, which was then responsible for distributing the tax equitably among its inhabitants. In a land of personal tax, i.e. personal income tax, this was sufficient.[To 2] A parcel-based cadastre was only necessary in countries of royal tax, where property rather than income was taxed, as in Haute-Guyenne,[4] in the generality of Limoges or in Auvergne,[5] or further south in Languedoc, where compoix were drawn up.[6][7] In countries of personal tax, the population was very wary of attempts to establish a parcel-based cadastre, seen as a means of increasing the tax burden. In 1763,[To 2][8][9] Henri Bertin, the controller-General of finances, was unsuccessful in this task. Bertier de Sauvigny's cadastre met with less opposition.[To 2]

Bertier de Sauvigny had all the less reason to undertake a parcel-based cadastre since the Court of Aids, in 1768, reaffirmed that the royal power could not interfere in the distribution of the taille (tax) in the parishes. Moreover, when he took over from his father Louis Jean Bertier de Sauvigny as Intendant of Paris, the latter had already limited the room for maneuver of parish taille collectors through a series of tariffs. Last but not least, a cadastre by masses of crops was much quicker to compile than a parcel-based cadastre.[To 2]

At the beginning of his administration, Bertier de Sauvigny was content to order surveys when he noticed anomalies. It was only gradually that the cadastral survey was systematized.[To 2]

Land registry men

Bertier de Sauvigny relied on subdelegates and surveyors to draw up his cadastre.

Subdelegates

The generality of Paris was divided into thirty-four elections and subdelegations, each headed by a subdelegate who assisted and represented the intendant. This is far more than in the other generalities of the kingdom. The subdelegate was chosen by the intendant. He was compensated by the intendant's gratuities, honoraria and judicature or municipal offices. He was often stable, sometimes succeeding his father in the position. He was assisted by a clerk and, like the intendant, performed duties in a variety of fields: justice, police, roads and finance.[To 3]

As regards the establishment of the land registry, the subdelegate organized the surveying of parishes and participated in their classification. He was responsible for administrative control of the surveying work, approving reports and plans, and reporting to the chief engineer-geographer, Pierre Dubray, on the quality of the surveyors' work. The surveyors did most of the fieldwork.[To 3]

Surveyors

Surveyors submitted their survey projects to the intendant's geographer, Dubray, and then to the intendant himself. If approved, they received a commission to survey a specific list of parishes. Pierre Dubray thus coordinated all surveying operations. He chose 82 surveyors, including members of his entourage: his son Guillaume, Lucien (who may have been his brother), his neighbor Denis Duchesne, and his apprentices Antoine Schmid and Pierre Villeneuve. The other surveyors came from all over the region, and generally surveyed parishes close to home.[To 4]

They were holders of a surveying license. This was considered a delicate profession, as it involved the ownership of land. They were therefore officers, and some were also notaries. However, these offices were of low value, ranging from 100 livres at the beginning of the eighteenth century to around 500 livres in 1772. The office provided certain privileges, such as exemption from gabelle, militia and taille collection. Surveyors were not the wealthiest of rural dwellers, but they did enjoy a certain financial ease, which enabled them to bear the costs of surveying operations, since they were only paid once the task had been completed. Pierre Dubray, whose professional skills were recognized and who played an important role in the entire operation, had a fortune of only 3,000 livres at his death in 1784, his office of surveyor and royal notary, worth 1,500 livres, having already been transferred to his son Guillaume. The latter's level of wealth, far from negligible, remained well below that of the wealthy ploughmen of the Paris Basin.[To 4]

The surveyors did not belong to the same social and cultural milieu as the king's engineers and topographers, who were involved in drawing up maps such as Cassini's and frequented learned societies. Surveyors were more field workers, trained empirically through apprenticeships, often within the family, like the Dubrays. However, they also had a certain bookish culture and possessed volumes on geometry and measurement methods.[To 4]

Drawing up the cadastre

Measuring surfaces

In accordance with his commission, the surveyor had to measure the masses of crops within each parish. First, the boundaries had to be established. Ecclesiastical parishes and tax parishes generally coincided in the countryside, but small towns, which constituted a single tax collection, were often divided into ecclesiastical parishes, while sometimes a hamlet was set up as a tax collection. The latter is clearly the circumscription used.[To 5]

Once the boundaries were known, the surveyor measured each type of land - woods, ploughland, meadows, etc. - and indicated it on a procès-verbal, using both the local unit of measurement and the king's measure, i.e. an arpent of 22 feet per rod and 100 square rod per arpent (51.07 hectares). These procès-verbal were recorded in notebooks of identical format.[To 5]

The metrological difficulties were considerable. While surface areas were almost always expressed in arpents, the value of the latter varied considerably. The King's arpent (51.07 ares) was used in just over a third of parishes, the common arpent (42.2 hectares) in a third, and the Paris arpent (34.18 ares) in around 10%. In all, the word arpent designated fifty different surface units, ranging from 30.64 hectares to 51.07 hectares. The number of square rods per arpent ranged from 64 to 100. The length of the rod ranged from 18 feet 11 inches to 25 feet, or from 5.84 m to 8.12 m.[To 6]

Surveying techniques were fairly straightforward. It involved triangulation, carried out with a chain or rope and a square. The surveyor measured the sides of the plot and then calculated its surface area according to its shape. To locate a right angle that could serve as a base, he used a square, also known as a surveyor's cross or surveyor's stick. As Bertier de Sauvigny's cadastre only surveyed large masses of crops, the surface areas to be measured were considerable and required the use of Pythagoras' theorem, which dispensed with the need to measure the third side in the field. It is not known what the intendant's instructions were for taking account of the terrain.[To 7]

Distances were measured with a chain rather than a rope, which shrank when wet. As the chain was heavy, the surveyor used a chain holder. There was also a more sophisticated device, the odometer. To measure angles, other instruments appeared: the planchette bearing an alidade, the graphometer, the theodolite or the quarter-circle. However, it is likely that the surveyors of Bertier de Sauvigny's cadastre did not possess these tools.[To 7]

Bringing the plan up

Next, the surveyor drew up a plan of the measured parish. This plan was not directly essential for the purpose of tax apportionment, especially as it was not based on parcels of land. In fact, the plan was both a tool for verifying the procès-verbal and the manifestation of a desire to control, see and represent space, typical of Lumières France. The scale used was around 1/6,000, close to the scale chosen for the Napoleonic cadastre, 1/5,000. These plans included the names of adjoining parishes, the direction of flow of rivers and cardinal points, with north not necessarily at the top of the sheet. The colors were applied in wash and were identical for all plans: woods in dark green, meadows in soft green, vines in yellow, ploughed land in pale earth color, buildings in carmine, rivers in blue.[To 5]

The surveyors were paid once they had received the plans and reports, which were checked and rectified if necessary. The surveying costs, paid by the collector of sizes in each election to the surveyor, were then charged to the parishes. The rate was three sols per royal acre, with no reimbursement for travel expenses, which were reduced as surveyors often lived at short distances. Local boundary markers were also paid.[To 5]

A 15-year effort

When Bertier de Sauvigny was killed at the start of the French Revolution on July 22, 1789, the land register was almost complete, and it was finished two years later. The work had lasted fifteen years. The documents currently preserved, plans and procès-verbaux, cover 95% of the collections. Certain areas were excluded, as they were exempt from pruning: the towns of Paris, Versailles and Poissy, and the large forests of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Meudon and Compiègne.[To 8]

The cadastre must have cost around half a million pounds to draw up.[n 1][To 8] Most of the work was carried out between 1783 and 1788, at a rate of 200 parishes surveyed per year, with no overall logic in the chronology, except for the margins of the generality, which were surveyed last. Most of the time, the task was completed within a year of the Intendant's order. Surveys took place mainly in spring, in April–May, with autumn being the second most favorable season.[To 9]

In the majority of cases, the surveyor failed to meet the one-month deadline normally set for him to deliver the procès-verbal and map. On average, he needed three months per parish for all the operations to be carried out. Pierre Dubray himself did not always meet the deadline, even though he had set it himself. The most punctual were Jean-Nicolas Devert, based in Rivecourt, who surveyed the greatest number of parishes (152), and Jean-Louis Droit, from Montereau-Fault-Yonne. Louis-François Durelle, based in Brienon-l'Archevêque, surveyed the largest area, nearly 150,000 ha, but at a slower pace. Pierre Dubray soon realized that the quality of work varied from surveyor to surveyor, and he held Devert up as a model, while criticizing and redoing the work of others, such as Pierre-Georges Doderlain.[To 10]

In exceptional cases, the whole process had to be redone. Surveyor Chevalier Closquinet de La Roche, entangled in local rivalries, failed to turn in a plan after more than a year. In December 1784, he lost the commission entrusted to him by the Intendant in 1783, and was replaced by another surveyor. The surveyors were closely followed by the subdelegates.[To 11]

In 98% of cases, the inhabitants welcomed the surveyor, whom they often knew, and did not object to the survey, which did not involve them personally since it was carried out by masses of crops and not by parcels. Only 2% of the total number of disputes concerned either the measurements themselves, or the appropriateness of the tax reform that led to the creation of the cadastre.[To 12]

From land registry to historical source

From one land register to another

Before it was decided to create a cadastre of parcels, Napoleon's first cadastre was drawn up by masses of crops. This first cadastral undertaking on a French scale seems to have been inspired by the experience of Bertier de Sauvigny's cadastre in the generality of Paris.[5]

The first surveys of Bonaparte's new cadastre by masses of crops were carried out just ten years after the last of Bertier de Sauvigny's cadastre, sometimes by the same surveyors. The temptation to repeat the measurements of the first cadastre instead of carrying out field surveys was therefore great. This is why the director of direct taxation for Seine-et-Marne, for example, had Bertier de Sauvigny's cadastral plans enclosed. However, it is clear that certain figures were copied from one cadastre to another.[To 12]

The accuracy of the intendance plans of the Bertier de Sauvigny cadastre is noteworthy. Comparisons with the first Napoleonic cadastre by mass of crops revealed discrepancies in surface area of around 10%, which is not very much. However, this may be due to the bias of copying. For some communes that have retained the same boundaries, the communal areas shown on the 1829 survey of the cadastre parcellaire are the same, to the nearest hectare, as those on the converted Bertier de Sauvigny cadastre.[To 13]

Valuable sources

Today, the survey reports and maps (known as " intendance maps ") drawn up for the land registry of Bertier de Sauvigny are preserved in the repositories of the departmental archives in:

These sources are used in a wide range of historical studies, at local and regional levels. Survey reports and intendance maps can be used to reconstruct landscapes and agricultural activities in general,[To 14][12] or to study certain activities in particular.[13][14] They are also used to study the transfer of land,[15] castles and their commons,[16] describe road networks[17][18] or hydrography,[19] contextualize archaeological excavations,[20][21] and more.

See also

- Cartography of France

Note: This topic belongs to "Maps " portal

Notes

- ↑ The sum of half a million pounds at the time corresponds to a sum of around eight million euros Conversion of 1783 pounds into euros.

References

- Touzery, Mireille (1995). Atlas de la généralité de Paris au 18th century. Un paysage retrouvé. Paris: Comité pour l'histoire économique et financière de la France. ISBN 2-11-087169-5.:

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 (Touzery 1995)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 (Touzery 1995)

- ↑ (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ (Touzery 1995).

- ↑ (Touzery 1995).

- Other sources

- ↑ Touzery, Mireille (1994) (in fr). L'invention de l'impôt sur le revenu: La taille tarifée 1715-1789. Histoire économique et financière - Ancien Régime. Paris: Comité pour l'histoire économique et financière de la France. pp. 251–358. ISBN 978-2-11-087168-8. http://books.openedition.org/igpde/2061. Retrieved 2021-12-21..

- ↑ Brian, Éric (1994) (in fr). La mesure de l'État. Administrateurs et géomètres au XVIIIe siècle. L'évolution de l'humanité. Paris: Albin Michel. pp. 253–254. ISBN 978-2-226-06870-5..

- ↑ Becchia, Alain (2012) (in fr). Modernités de l'Ancien Régime (1750-1789). Histoire. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. pp. 390–391. ISBN 978-2-7535-1994-7. http://books.openedition.org/pur/116433..

- ↑ Touzery, Mireille (2007). "Le mariage de la carpe et du lapin : le cadastre de Haute-Guyenne, une initiative d'une assemblée provinciale en pays d'élections et de taille réelle, 1779-1789" (in fr). De l'estime au cadastre en Europe. L'époque moderne. Paris: Comité pour l'histoire économique et financière de la France. pp. 391–416. ISBN 978-2-11-094791-8. http://books.openedition.org/igpde/9758..

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Fougères, M. (1943). "Plans cadastraux de l'Ancien Régime" (in fr). Mélanges d'histoire sociale 3 (1): 55–70. ISSN 1243-2571. https://www.persee.fr/doc/ahess_1243-2571_1943_num_3_1_3078..

- ↑ Jaudon, Bruno; Bourillon, Florence; Vivier, Nadine (2012) (in fr). La mesure cadastrale : Estimer la valeur du foncier. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes. pp. 101–120. ISBN 978-2-7535-6864-8. http://books.openedition.org/pur/113586.

- ↑ Jaudon, Bruno (2014) (in fr). Les Compoix de Languedoc. Impôt, territoire et société du XIVe au XVIIIe siècle. Bibliothèque d'histoire rurale. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes. ISBN 978-2-911369-11-7..

- ↑ .Touzery, Mireille (2001). "La monarchie française et le cadastre au XVIIIe siècle : entre taille réelle et taille personnelle" (in fr) (PDF). Jahrbuch Fur Europäische Verwaltungsgeschichte 13: 217–246. https://www.academia.edu/1757959.

- ↑ Alimento, Antonella (2008) (in fr) (PDF). Réformes fiscales et crises politiques dans la France de Louis XV: De la taille tarifée au cadastre général. Bruxelles: Peter Lang, Editions Scientifiques Internationales. ISBN 978-90-5201-414-2. https://www.academia.edu/36445205..

- ↑ Gautier-Desvaux, Élisabeth (2008). "Des cartes, plans et maquettes aux supports électroniques : la conservation des supports spécifiques aux Archives des Yvelines" (in fr) (PDF). Jahrbuch Fur Europäische Verwaltungsgeschichte 13: 217–246. https://www.persee.fr/doc/gazar_0016-5522_2008_num_209_1_4465.

- ↑ (in fr) Paysages d'Yvelines à la fin du XVIIIe siècle: le cadastre de Bertier de Sauvigny. Versailles: Archives départementales des Yvelines. 1996. pp. 251–358. ISBN 2-86078-006-8.

- ↑ Clout, Hugh D.; Gay, François (2002). "Le Pays de Bray : un lieu de mémoire" (in fr). Études normandes 51 (4): 87–99. https://www.persee.fr/doc/etnor_0014-2158_2002_num_51_4_2866.

- ↑ Quellier, Florent (2003) (in fr). Des fruits et des hommes. L'arboriculture fruitière en Île-de-France (vers 1600-vers 1800). Histoire. Rennes: |Presses Universitaires de Rennes. ISBN 2-86847-790-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=NAUdCwAAQBAJ..

- ↑ Rabasse, Jacqueline; Bennezon, Hervé; Mérot, Florent; Rentet, Thierry (2011). "Le vignoble et la forêt de Montmorency à la croisée des échanges" (in fr). Paris et le nord de l'Île-de-France sous l'Ancien Régime. Relations, échanges et interdépendances entre une capitale et ses pays ruraux. Paris: Nolin. pp. 17–23. ISBN 9782910487454..

- ↑ Herment, Laurent (2012) (in fr). Les fruits du partage : Petits paysans du Bassin Parisien au XIXe siècle. Histoire. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes. ISBN 978-2-7535-6884-6. http://books.openedition.org/pur/130656..

- ↑ Morin, Christophe (2008) (in fr). Au service du château : L'architecture des communs en Île-de-France au XVIIIe siècle. Histoire de l'art. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne. ISBN 978-2-85944-580-5. http://books.openedition.org/psorbonne/540..

- ↑ Mérot, Florent; Bennezon, Hervé; Mérot, Florent; Rentet, Thierry (2011). "Une vallée en son royaume. l'ouverture de la vallée de Montmorency aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles" (in fr). Paris et le nord de l'Île-de-France sous l'Ancien Régime. Relations, échanges et interdépendances entre une capitale et ses pays ruraux. Paris: Nolin. pp. 41–62..

- ↑ Dhermy, Arnaud (2014). "Une cartographie des rocades ? Contourner les villes avant l'ère des ingénieurs" (in fr). Composition urbaine et réseaux. Actes du 137e Congrès national des sociétés historiques et scientifiques, « Composition(s) urbaine(s) », Tours, 2012 137 (8): 29–44. https://www.persee.fr/doc/acths_1764-7355_2014_act_137_8_2703.

- ↑ Derex, Jean-Michel (2000). "Les étangs briards de la région de Meaux à la veille de la Révolution" (in fr). Histoire, économie & société 19 (3): 331–343. https://www.persee.fr/doc/hes_0752-5702_2000_num_19_3_2122.

- ↑ Gentili, François (1997). "Baillet-en-France (Val-d'Oise). Le Fayel" (in fr). Archéologie médiévale 27 (1): 141–142. https://www.persee.fr/doc/arcme_0153-9337_1997_num_27_1_905_t1_0141_0000_2.

- ↑ Dufour, Jean-Yves (2016). "Une faisanderie moderne à Saint-Pathus (Seine-et-Marne)" (in fr). Revue archéologique du Centre de la France (55). ISSN 0220-6617. https://journals.openedition.org/racf/2340.

Bibliography

- Touzery, Mireille (1994) (in fr). L'invention de l'impôt sur le revenu: la taille tarifée 1715-1789. Histoire économique et financière - Ancien Régime. Paris: Comité pour l'histoire économique et financière de la France. ISBN 978-2-11-087168-8. http://books.openedition.org/igpde/2061. Retrieved 2021-12-21.

- Mireille Touzery (1995) (in fr). Atlas de la généralité de Paris au XVIIIe siècle. Un paysage retrouvé. Paris: Comité pour l'histoire économique et financière de la France. ISBN 2-11-087169-5.

|